In the depths of the pandemic, I listened to guru Mashangva’s music. It reminded me of home, the pounding of village life, and the distinct earthy, sonic landscape of Northeast India. I could sense the texture and the languid flow of languages, the sometimes busy and quietude of everyday life, the hilly terrain and rain-soaked green of tropical forests, and the deep abiding love for music. The ease of his singing, the uncomplicated manner of his chord structure, and the equally sensuous evocation of place and identity, through the drone of the blues guitar, reminded me of the simple things in life. Simplicity is what guru always asks of his music and his listeners. It is his philosophy wrapped in an ecology of creation that is about sound, nature, the words of his ancestors, and sometimes mimicking the unvarnished tone of his heroes, the two Bobs – Dylan and Marley.

When guru performs, he wears the Raivat Kachon, which is a traditional Tangkhul body cloth. Alongside this, he wears various necklaces, sometimes a bird feather, but always with a traditional Naga haircut (kept long at the back and shaved along the sides), and a pair of leather boots. With an acoustic guitar, and harmonica – this is the brand, the persona that identifies guru. This stage persona defines his music and his identity – people know that he is Naga through his presence. ‘It’s not just his music, but it’s his lifestyle’, Alobo Naga, a musician from Nagaland, told me. ‘Rewben is Rewben. I don’t think I know anybody who sounds and sings like that’ (see images; used with permission from guru).

Guru is a Tangkhul Naga from Choithar, a village in the Indian state of Manipur. He now lives in the capital, Imphal, though regularly travels northeast to Ukhrul, the district headquarters of his village. The title ‘guru’ was bestowed on him by the North East Zone Cultural Centre (NEZCC) in 2004, an institution under the Ministry of Culture, in the state of Nagaland. It is a state patronage that was established to celebrate the cultural diversity of India under the Guru-Shishya-Parampara scheme (teacher-student-tradition), and guru Mashangva received it for his contributions to folk music. In its latest advert, the NEZCC calls on candidates to apply who have ‘thorough knowledge for imparting training in any cultural field of the region, i.e. folk dance/songs, bamboo/cane/wood craft, folk theatre, woodcraft, mask making etc., emphasis is given on Dying & Vanishing art forms of the region’. For 1 year, the guru will train 4 shishyas (or students), with monthly stipends for all those involved. This is quite a large scheme; when guru Mashangva was an awardee, there were approximately 20 others from all over the Northeast, and the position lasted for 2 years. Some gain prominence through this scheme; others quietly fade away from public view. As part of this, and through the years, 15 shishyas have studied under guru Mashangva, so that they in turn might become teachers of traditional folk music and revivors of Tangkhul culture.

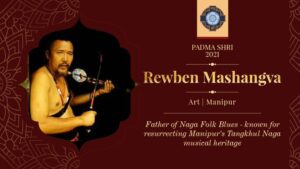

The title of guru bestowed on him by the Ministry of Culture has enabled Mashangva to attain a larger profile, resulting in cultural and political capital. It has given him global recognition. Amongst the many national and regional honours he has received is the fourth highest civilian award, the Padma Shri, which he was given in November 2021. Here guru governmentality and guru logics, the legitimation of authority by the state, release a kind of power. According to Michel Foucault, ‘“Government” did not refer only to political structures or to the management of states; rather, it designated the way in which the conduct of individuals or of groups might be directed – the government of children, of souls, of communities…To govern, in this sense, is to control the possible field of action of others’ (emphasis added). This kind of rationale, that creates the condition for the exercise of power, is captured in the notion of a state sanctioned ‘guru’, but also in the cultural capital that this term confers.

In the Northeast of India, ‘guru’ is a term that is fraught with associations with ‘Hinduism’, associations that have been exacerbated by the continuing Indian militarisation of the region and the fact that Christianity dominates large portions of the hill areas of Manipur and states such as Mizoram, Nagaland and Meghalaya. Historically, at least, the presence of the Indian military/state was seen as Hindu hegemony over a tiny recalcitrant Christian population, especially where armed struggle over sovereignty was sometimes couched in the language of religion. However vexed the translation of the term may seem, at least for guru his vision is that of a teacher. He told me: ‘we have lost our culture and tradition and now it has become dark. So to bring light, a teacher is needed to light a candle, a lamp’. Guru, in his interpretation, means someone who is attempting to bring light to a world that has forgotten its roots.

The blues music and its evocation of roots are central to the sonicity of his guruship. Sound, as Jonathan Sterne reminds us, is ‘a little piece of the vibrating world’. For guru, the sounds he creates – from the Tingteila (folk fiddle) to the Yangkahui (flute) – is grounded in the natural rhythm of his village; it is about combining both human and nonhuman elements in his ecology of creation. He tells me how his music imitates nature. The sound of the cicada (an insect) is present in his music – ching, ching, ching. In an interview with The Hindu newspaper, he discusses one of his own compositions, which he calls ‘The Cicada Song’. He says: ‘Each season sounds different, have you noticed? In winters grass has dried, in the spring the new leaves blow with the wind, in the rains the water trickles at different speeds, it’s all music’. He also uses the horn of the Indian bison, or mithun, and cuts it to produce certain sounds – if the horn is long, it produces the A scale, if shorter, it’s the C scale. Even when creating his Indigenous instruments, such as the Tingteila or the Yangkahui, the wood comes from the forests his ancestors used, wood that was used for building log drums – a drum traditionally at the centre of a village, which usually averaged 10 metres long and 4 metres in width, and is hewn from a single, carefully selected tree with the head representing an animal or human figurine. These drums were used for celebrating victory and the taking of human heads. Marking village feasts and funerals of the famous, each occasion had its own special rhythm.

The first song that really put guru on the map was Changkhom Philava. It is an interesting fusion of folk, blues (Eric Clapton and Roy Buchanan), the ‘Tulsa sound’ (blues, rockabilly, country and jazz) popularised by J.J. Cale, and hints of Bob Dylan’s bracing, honest tone, with the chirping song of the cicada in the background. In many ways, Changkhom Philava would set the standard, the kind of approach guru was keen on exporting, a musical journey that would define him.

It is abundantly clear that two of his musical heroes are Bob Marley and Bob Dylan. Reflecting on Marley’s music, he recalls how Redemption Song (1980) allowed him to reflect on his own situation in Manipur.

The lyrics and the sounds are very close together and it really reflects Naga village life – where we are also singing about oppression and yearning for freedom. Even though we were very rudimentary in our civilisation and although we don’t have many facilities, we were living freely. But now the Indians and the Meitei community in Manipur – the majority – are exploiting us socially and economically. So Redemption Song reflects our situation. Emancipation is about freedom from mental slavery.

Drawing on Marley’s notion of roots, where he says (according to Anungla Zoe Longkumer, a Naga musician and activist, in our interview) ‘some are leaves, some are branches, but I and I are the roots’, the festival Roots and Roots on the Move was organised in the 2000s by activists such as Keith Wallang and Anungla Zoe Longkumer. It was an attempt to unify and relate the various communities across Northeast India by appealing for a return to their identity in land, tradition and music. It was about creating a ‘method of hope’ for those who were experiencing the debilitating stranglehold of the military conflict, the lack of infrastructural development, and the increasing malaise and ennui brought about by corrupt regional systems that privileged only a few. Singing and performing was one way to rage against the system, but also to cultivate pride in their identity and tradition.

For guru, Bob Dylan’s musical influence was paramount. Blowin’ in the Wind (1963), along with Chimes of Freedom (1964), had a significant impact through Dylan’s lyrical ability to relate to real life events. Guru says, ‘Like how many years have we been asking for sovereignty? How many times, and how many more years do we have to wait to call us a man? Dylan’s songs highlighted our yearning for freedom, peace, justice’. Blowin’ in the Wind was the first Dylan song that he learnt to play, giving it a guru Mashangva twist.

When I heard his guitar and vocal delivery, I really felt good. Some of the village elders, when they joked, their jokes and their delivery sounded so much like Dylan’s positivity in his songs. That feeling was present. Like when one listens to the stories, the humour, and the happiness – that was the feeling. Sometimes Dylan was just talking, sometimes singing. So this really touched my heart and so I wanted to convey this kind of feeling and sing these kinds of songs.

Guru Mashangva and his frequent lyricist and collaborator, Ngachonmi Chamroy, realised the power of fusing two musical genres that spoke, on the one hand, to the popularity of western popular music in the Northeast – from the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Bob Marley and Bob Dylan, to the influence of glam rock, blues, and heavy metal that shaped much of the musical outlook in the region. On the other hand, guru and Chamroy wanted their music to be an open enquiry, a kind of experiment with fusion, with a lyrical and musical sensibility attuned to their roots. For example, one of the first musical fusions guru attempted was during the Naga Student Federation (NSF) conference in Ukhrul, 1992. He borrowed Dylan’s lyrics to Trust Yourself (1985), and fused that with a traditional Tangkhul song about a girl called Ayesho. He recalls how the two – Trust Yourself and Ayesho – blended effortlessly to the extent that the metre matched perfectly. He sings to me: ‘Trust yourself, Trust yourself to do the things that only you know best…’

Central to his understanding of guruship is the transmission of knowledge. Many come to see him play: rock musicians, church singers, and those with an interest in music. He tells them about the songs that humans engage in, inspired by nature and how storytelling is in song. ‘We don’t have a book to share’, he says, ‘but we must engage in the oral tradition of passing down knowledge, a parampara’.

Freddy, who is a Baptist pastor, musician, and entrepreneur, remembers the first time he heard guru Mashangva. It was in 1995, he recalls. It was an old videotape of guru’s performance in Ukhrul during the 1992 NSF conference. ‘Instantly’, Freddy says, ‘I fell in love with his music’. Freddy had been playing covers of the British band, Iron Maiden, and was massively influenced by the glam rock of the 80s and 90s, only to see ‘this guy come to the stage with his guitar, his haircut and playing traditional tunes, mixed with blues – this was all novel to us’. Indeed, one of the signature musical techniques guru has adopted from the blues, and is frequently part of his repertoire, is the slide, which creates a gliding effect (or a glissando) and deep vibratos to his songs, resembling the human voice.

The band that Freddy formed called Salt and Light Travelling Band fuses traditional music with metal and reggae. Like guru, he too wears the Raivat Kachon (Tangkhul body cloth), cuts his hair in the style of guru, and fuses various genres of music. But the band’s lyrics are Christian gospel. Their idea, Freddy says, is to ‘present the gospel to a secular stage’.

Augustine is another musician influenced by guru and is from the band Featherheads. They combine traditional Naga music with rock and metal. His is a story of travel and uprootedness that he experienced as a child. Due to his parents’ jobs they moved around all over India, he says, like ‘hippies and gypsies’. He had very little connection with his community in Ukhrul, which he now regrets. He trained as a DJ in Pune after listening to Linkin Park, an American rock band. It was during DJing that Augustine founded a number of bands – first Systemic Roots and then Featherheads – that were inspired by a variety of musical genres. They listened to bands like System of the Down, Bullet for My Valentine, and specially gravitated towards the Finnish symphonic metal band, Nightwish. Their ability to combine traditional Finnish folk and new metal genres gave Augustine inspiration to carry on with Featherheads. When Augustine moved back to Ukhrul, he met up with guru. He had already heard of guru’s early songs like Changkhom Philava and, like guru, he began to adopt the Naga hairstyle, clothes, and fusion music. What drew him to guru was not only his music, but ‘his way of becoming himself’. He is guru but also Awo (in Tangkhul), an elder, who represented his vision of ‘our love of ancestors’. Guru showed Augustine and the band how to bridge the time of tradition and that of modernity. In sonic terms, this highlights the ability to recognise sound and place as sensed through their motion across space and time, remaining true to who they are as a people; perhaps guru’s way of becoming himself is marked by these capacious temporal and spatial constellations.

Guru Mashangva is a guru in many keys. He is now well known beyond the region of Northeast and has attracted attention through his numerous YouTube clips (for instance his collaboration with the popular Bangalore band, The Raghu Dixit Project), documentaries on his life and work, and various magazine articles about his music.

Music is not only about the collective habitation, representation, and performance of culture. For guru, it is about shining a light on a path for others to follow. To be as a way of living and taking pride in one’s work, that’s the true nature of a guru.

Arkotong Longkumer, Senior Lecturer in Modern Asia at the University of Edinburgh.

Leave a Reply