Beloved and Betrayed: Mediated Love in a Guru Movement

Guest post by Tulasi Srinivas

On 27th April, 1997, I stood on the dusty verge of the main street of the provincial town of Puttaparthi in south India, about 100 miles from my hometown of Bangalore. In front of me was the ornate pastel-hued gateway of the Prasanthi Nilayam ashram, the spiritual home of the international Sathya Sai movement, named after its founder, the charismatic guru, Sri Sathya Sai Baba. The gateway bore the insignia of Sathya Sai Baba – a lamp with the rising sun behind it, the symbols of the five major world religions – Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Zoroastrianism and Buddhism – resting on an open lotus. Etched on the rear of the gate, in gold, was the motto of the movement, “Love all, Serve All”.

This exhortation – to love and to serve – etched on the gates to the ashram, I had seen repeatedly stamped on postcards and on flyers in Australia, on butter and yogurt containers in the US, on cassette covers, cards and DVD holders in Singapore, on pens, posters and key rings in Europe, and appearing on all variety of Sai media including YouTube video, television, statues, calendars and voice recordings, all over the world offerings to devotees and to spiritual seekers, as Warrierhas termed them, as part of Sathya Sai Baba’s guru “brand”.

This exhortation – to love and to serve – etched on the gates to the ashram, I had seen repeatedly stamped on postcards and on flyers in Australia, on butter and yogurt containers in the US, on cassette covers, cards and DVD holders in Singapore, on pens, posters and key rings in Europe, and appearing on all variety of Sai media including YouTube video, television, statues, calendars and voice recordings, all over the world offerings to devotees and to spiritual seekers, as Warrierhas termed them, as part of Sathya Sai Baba’s guru “brand”.

This essay marks the first pass at thinking about the provocation offered by the saying on the gate, to love and to serve the guru. While this inquiry passes over and through different kinds of gurus and guruship in general, it does not attempt to make the claim that all gurus are variations of a single historical type, or emerge from some common understanding. Rather it asks; What might we learn of the practices of devotion to the guru if one is expected to love him or her as god, regardless of their human fallibility?

This inspirational saying was instantly recognized by Sai devotees worldwide as evidence of devotion and service to the charismatic guru godman, Sathya Sai Baba himself, who, as Copeman and Ikegame (2012) have suggested in their study of guruship, overflowed contained categories. Devotees saw Sai Baba as uncontained and uncontainable love.

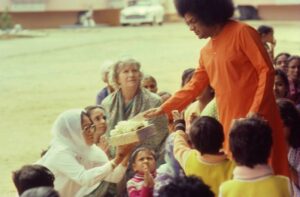

Such devotees spoke adoringly of Sai Baba’s daily darshan at Prasanthi Nilayam where he offered viewings of himself to the assembled crowd of devotees as evidence of his love and service.

During these darshan services Sai Baba often gave rambling and seeming impromptu sermons on love. He urged his followers to be loving towards one another, to “be the wave on this ocean of love”. In a speech in 1986 he exhorted them, “to see god in everything, to love everything as manifestations of god, and to offer everything to god as an offering of love” (Santhana Sarathy 1986). For devotees there was a conjunct between life and love. They often talked about loving god, being loving, and overflowing with love. For they believed Sai Baba when he stated in his sermons that “life itself is love” (Sathya Sai Speaks, XI:222).

Devotees complied his many sayings on love and filmed Sai Baba on Sai television and later on YouTube videos, encouraging a slippage between devotion and love, a deep cultural theme in religion of the subcontinent. In Hindu myth and theology, and through the Bhakti movement extended to subcontinental Islam, the devotee and god are seen as estranged lovers waiting to be reunited, where eros or erotic love was blurred with philia or affection and devotion. Or as Sai scripture puts it, cultivating love was essential to truthful devotion, “Winning Love through Love is the vital aspect of devotion”. The exchange of love between Sai Baba and his followers gave them certitude in his love for them. The question of uncertainty in that corner of life where we most long for security and grounding was banished and devotees revelled in the joy of loving and being loved.

But what can this transformative love of the guru teach us about the guru, him or herself?

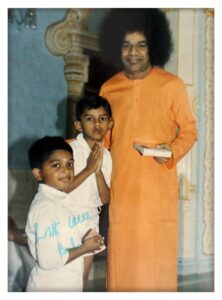

With his distinctive orange robe and halo of hair made Sai Baba unusual, watchable, charismatic, beloved, overflowing with what the Greeks would term ‘agape’, the kind of unexplainable love that initiates a fellowship with god. Sai Baba himself encouraged this view stating that his “form was love”. And devotees read this form as lovable and they wanted to be close to him, physically and emotionally. Devotees spoke of feeling his love for them, and they returned it multifold. He called them “Bangaru”, the Golden Ones, and told them that after he “left his body” he would be reincarnated as Prema or complete love. For them, he suggested, he would be reborn as a young boy known as “Prema Sai.”

For many decades while Sai Baba was alive, devotees understood the exhortation to love and to serve as openings to the possibility of a proxemic closeness to Sai Baba himself, which Lucia (2014) has argued has a certain aspiration to touch him as an avatar of god, a “haptic logic” of touching the divine. And the possibility of touch existed as a reality for devotees as Sai Baba would parade along the aisles between the closely packed bodies during a darshan, offering himself to be viewed, sometimes engaging with “lucky” devotees, speaking to them, pressing the flesh, offering solace and magical gifts. His touch was thought to be magically healing, to be revelatory and devotees yearned for it, pressing close to him as he passed by them. Indeed, devotees were so crazed for his touch that he had to have a security detail follow him during the darshan to prevent the crowd rushing him and doing him harm.

According to the devotee grapevine Sai Baba’s picking of certain individuals for private darshan, for his complete attention, was to reward them for their service to the Sai community. That love came at the cost of service. Devotees understood their own lives as one of endless love and service where unquestioning love of Sai Baba and service to the community might allow them into his divine presence. And they saw Sai Baba’s life through that trope as well, and stories of his love for his devotees and his service to the community and the world were always on their lips.

In my book, Winged Faith: Rethinking Globalization and Religious Pluralism Through the Sathya Sai movement (Columbia University press 2010) which I wrote after a decade-long ethnographic study of the Sathya Sai movement, I said that Puttaparthi was a city that resonated with such spiritual conversations and stories about love.

But is the form of the guru, as Cohen so brilliantly suggests, a doubled site of both critical transformation and danger, as well as a copy of “all too human” forms of instruction on desire (Cohen in Copeman and Ikegame 2012: 108)?

Indeed there was a darker hidden side to love that it was forbidden to speak about at the ashram. Sexual love, particularly for unmarried devotees, was deemed inappropriate and sinful. This love was kept hidden, unmediatized, and unspoken about except in terms of punishment. Sai Baba urged his unmarried devotees to be celibate and insisted they live only in gender specific dormitories in the ashram. They felt they were suspect, watched and made to feel guilty, and if found in forbidden sexual activity, they were cast out and shamed. Devotees were frightened of being found to have broken dormitory rules by Sai volunteers, and being exiled from Sai Baba’s presence. Rumours abounded at the ashram of Sai Baba’s strict rules on this matter and his displeasure at devotees who broke the rules. These oscillation of certitudes and uncertainties of love were disorienting for many devotees and in secret they expressed their fear and unease.

Indeed there was a darker hidden side to love that it was forbidden to speak about at the ashram. Sexual love, particularly for unmarried devotees, was deemed inappropriate and sinful. This love was kept hidden, unmediatized, and unspoken about except in terms of punishment. Sai Baba urged his unmarried devotees to be celibate and insisted they live only in gender specific dormitories in the ashram. They felt they were suspect, watched and made to feel guilty, and if found in forbidden sexual activity, they were cast out and shamed. Devotees were frightened of being found to have broken dormitory rules by Sai volunteers, and being exiled from Sai Baba’s presence. Rumours abounded at the ashram of Sai Baba’s strict rules on this matter and his displeasure at devotees who broke the rules. These oscillation of certitudes and uncertainties of love were disorienting for many devotees and in secret they expressed their fear and unease.

Unfortunately, the dormitory was not the only space where sex and love went awry, even to the point of criminality. Despite his strictures on love, Sai Baba himself was accused of groping and of touching underage boys in his rooms during what was termed “private darshan”. Former devotees discussed his sexual proclivities, his sexual harassment and assault of young men, documenting allegations and instances of assault on webpages and in legal suits, and calling for legal and political action. Former followers felt betrayed that Sai Baba stayed in place as a revered godman, whilst devotees felt betrayed by the allegations made against their chosen god. And this was complicated by the fact that, for devotees, the guru’s touch was divine, and being touched by him, however inappropriately, was seen as a precious and much valued gift of love.

The accusations of sexual assault and groping received global attention in 2004 when the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) aired The Secret Swami, a documentary featuring interviews with American male devotees who claimed that Sai Baba had coerced them as young men into sexual relationships. They described how he initiated them into such relationships by touching them, by massaging their genitals, and then demanding sexual favours, in some cases for many years.

Sai devotees instantly rushed to his defence claiming that this was a cultural misunderstanding and that this was god initiating these young devotees into divine tantric love and devotion. They suggested that his touch should be interpreted not as human sexual groping but as the highest form of divine love. Former devotees scoffed at their seeming gullibility.

Tracing this warped “love”, lust and betrayal backwards in time, former devotees claimed that it boiled over on the night of 6th June 1993 when four young men broke into Sai Baba’s bedroom with knives, and attempted to assassinate him. Sai Baba escaped unharmed by locking his bedroom door and escaping via a ladder. Newspapers reported at the time the bald fact that six people died in this attempt; two Sai devotees killed by the assailants, and the four assailants who were gunned down by Sai Baba’s security forces and local police. As the inquiry was quickly quashed and the assailants’ motives remained a mystery. Some newspapers speculated it was a coup attempt since Sai Baba’s spiritual empire was worth several million dollars. But others saw it as a desperate attempt by the victims of assault to get even, having suffered a betrayal of their devotion and their love.

“I always teach you love, love and love alone,” Sai Baba is recorded as saying on 15th April, 2004. But it would seem that in thinking about gurus and other charismatic leaders, love is speculative, returning to us in what we do and do not know.

Tulasi Srinivas, Professor of Anthropology, Religion and Transnational Studies, Emerson College.

Bibliography

Copeman, Jacob and Aye Ikegame. 2012. The Guru in South Asia: New Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, Lawrence (2012) “The Gay Guru: Fallibility, unworldliness, and the scene of instruction.” in Copeman, Jacob and Aye Ikegame. 2012. The Guru in South Asia: New Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lucia, Amanda. 2014. Reflections of Amma: Devotees in a Global Embrace. Berkeley: University of California Press

Srinivas, Tulasi. 2010. Winged Faith: Rethinking Globalization and Religious Pluralism through the Sathya Sai Movement. New York: University of Columbia Press.

Warrier, Meera. 2003. Guru Choice and Spiritual Seeking in Contemporary India. International Journal of Hindu Studies 7 (1-3):31-54 (2003)