Lecture 3. Freedom Fighter or Terrorist? John Brown and the American Civil War

This blog gives a summary of Neiman’s third lecture in her series. The focus is on John Brown and it presented an overview of his life and actions and argued why he should be seen as a hero. Below the summary is a response from Kofi Akan Brown, a masters student in Religious Studies and the video recording of the lecture.

Terrorist, lunatic or hero? And how can one man be presented as all three?

Reverend Moncure Conway of Ohio, two days after Brown was hung in 1859 for leading an insurrection to free slaves lamented the ‘stupidity’ of his age for seeing Brown as mad or as a traitor. Neiman shared that her interest in Brown was sparked by a wave of suicide terrorism which was followed by the slogan ‘one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter’, which, she claims, makes either claim equally valid and rational.

From growing up in the States, Neiman shared that the legacy of Brown and questions around the civil war both lack clarity. Herman Melville believes Brown was the spark that ignited this war. Britain banned slavery in 1833, Queen Victoria is reported to have cried when reading Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and abolitionist were loud and risk-taking. Yet Neiman poses that Brown went beyond rousing passions, and tempered them instead. The context also assisted, where the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, the 1857 Law that asserted that blacks could not have rights or citizenship, and the 1854 that extended slavery beyond the South imposed these moral abolitionist questions on the North. The economic success of the cotton industry also pushed for plantations to expand West into Native American areas- also expanding their political remit to receive a majority for slave owning States. Kansas became a hot-pot of immigration, from both pro-slavery and abolitionist migrants.

Brown was born in 1800 in Connecticut. Hs father owned a small farm and his grandfather was a captain in the Continental Army. Calvinism was an important familial element, especially the evangelistic idea of all souls being equal to God. John Brown’s father was an abolitionist and John’s own passion was kindled at the age of 12 when witnessing the mistreatment of a slave boy in a house where he was staying. Brown’s modest household with 20 children invited black people to dinner, but the death of the Presbyterian minister Elijah Lovejoy caused him to consecrate his life to abolitionist cause at a church Assembly. Already they were active in helping transport fugitives to Canada and supported a small black farming community. In 1854 he sent five of his sons to Kansas with the view of following. The journey however was difficult and one of his grandsons died from cholera. The riverboat which carried the family was captained by a pro-slavery man who left without them. They travelled the remainder of the way via stagecoach without food because of their Northern accents. The family once arriving lived in challenging circumstances, facing harassment and abuse from pro-slavery neighbours- 75% of the violence in the State was caused by pro-slavery supporters.

Brown held slavery to be an undeclared war by one part of the population against the other, and believed that violent resistance to it was a matter of calling the slaveholders to reckoning.

This violence extended to Senator Sumner who was almost beaten to death.

This pushed Brown to organise a vigilante party of seven (four being his sons) to kill five pro-slavery neighbours. The Browns and allies escaped from being caught with the help of local Native Americans. He released most of the men he captured and gave them a lecture and was considered to have won a moral victory. Brown studied the slave insurrection in Haiti and Jamaica and believed that freeing slaves and raiding plantations would eventually make the regime fall. He however severely lacked men. With just six black and thirteen white volunteers he captured the federal armoury at Harper’s Ferry, a number of hostages and Colonel Lewis Washington- a small plantation owner and great grand-nephew of the first US President.

This pushed Brown to organise a vigilante party of seven (four being his sons) to kill five pro-slavery neighbours. The Browns and allies escaped from being caught with the help of local Native Americans. He released most of the men he captured and gave them a lecture and was considered to have won a moral victory. Brown studied the slave insurrection in Haiti and Jamaica and believed that freeing slaves and raiding plantations would eventually make the regime fall. He however severely lacked men. With just six black and thirteen white volunteers he captured the federal armoury at Harper’s Ferry, a number of hostages and Colonel Lewis Washington- a small plantation owner and great grand-nephew of the first US President.

“Brown relished the symbolic justice: George Washington founded a nation that fought for liberties it denied to black men; now black men were guarding his descendant with iron pikes.”

The hostages reported that they were treated well but Brown was captured. His “Secret Six” all fled but one, including Frederick Douglass who, being black, could not have even dreamed of a fair trial. Neiman highlights how the Transcendentalists Thoreau and Emerson intensely supported Brown despite their previous distance from political activity. Thoreau praised Brown’s ‘common sense’ which Neiman suggests is best shown through his cool manner during his trial and imprisonment. Emerson argued against the killing of Brown because of his integrity, truthfulness and courage and compared the gallows of Brown to the cross of Christ. 1400 mourners attended his memorial service in Cleveland.

The Weekly Anglo-African newspaper published a letter sent to Brown’s wife from “your coloured sisters”, “We are a poor and despised people – almost forbidden, by the oppressive restrictions of the Free States, to rise to the higher walks of lucrative employments, toiling early and late for our daily bread; but we hope – and we intend, by God’s help – to organize in every Free State and in every colored church, a band of sisters, to collect our weekly pence, and pour it lovingly into your lap.”

W. E. B. Du Bois declared that Brown ‘did not use argument, he was himself an argument’ in the sense that Brown embodied his passions. That devotion made Emerson and Thoreau regard him as a true Transcendentalist. Neiman praises his ability to move minds in the States, despite, she claims, his lack of formal education. He visited Boston in 1857 in search of money and was invited to Emerson’s home and to lecture at Cambridge Town Hall. His plans were cunning. He toured Europe and studied Waterloo and fortifications in Germany and Switzerland to come up with his master plan to dent the slavery economy with his few men.

‘A hero is willing to live for an idea, indeed to do everything possible to live for and with an idea before concluding it is necessary to die for it.’ Neiman praises Brown’s dedication to finding the most effective way to combatting slavery, beginning with non-violent acts such as giving up his seats at church for fugitive slaves in Ohio, and even in the most passionate of situations he had a patience that should be celebrated, emphasised Neiman. Additionally, she commented on the principles that were held by his camp and men, without alcohol, profane language or immoral character. She also touched upon Brown’s fondly remembered gentleness, especially towards children.

“Brown was considerably ahead of the Concord intellectuals who would come to support him. In the 1830s, as Brown was working to create an interracial settlement in the Alleghenies, Emerson was writing in his diary that neither the African, the Irish, the American Indian nor the Chinese would ever “promise to occupy a very high place in the human family.” (Rey 220) The Transcendentalists opposed slavery but not racism.”

Neiman defends Brown against the accusation of being a madman by comparing him to Nat Turner, a slave who led a much wilder and bloodier rebellion in Virginia twenty years earlier but who was never accused of insanity. Rebelling against one’s own oppression was somehow expected, but rebelling for someone else seemed crazy. A 2020 series even paints Brown as a lunatic.

In fact, as the following lectures will make clear, my own heroes are universalists, those who took risks to uphold the fundamental dignity of all humankind […] The most remarkable heroes act over the promptings of instinct and tribal loyalties.

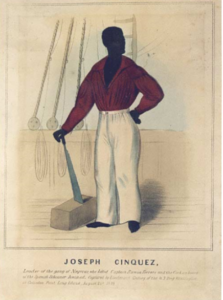

Brown himself highlighting the noble success of Joseph Cinque, an enslaved Africa on a Portuguese ship and brought to trial for mutiny and murder reveals how awar e he was of the sympathies of his time, stating that one man’s defence of his rights provokes more emotional reaction than the suffering of three million. “Since oppression always relies on dehumanizing its victims, portraying victims’ humanity is crucial […] Pity and empathy can be spurs to action, but alone they rarely inspire. For among the human qualities we most value is dignity […] Like Cinque, the six black men who died in the raid at Harper’s Ferry revealed a dignity that belied Southern stereotypes of degraded subhumans, as the white men, belied the Southern image of Yankees as timid traders.”

e he was of the sympathies of his time, stating that one man’s defence of his rights provokes more emotional reaction than the suffering of three million. “Since oppression always relies on dehumanizing its victims, portraying victims’ humanity is crucial […] Pity and empathy can be spurs to action, but alone they rarely inspire. For among the human qualities we most value is dignity […] Like Cinque, the six black men who died in the raid at Harper’s Ferry revealed a dignity that belied Southern stereotypes of degraded subhumans, as the white men, belied the Southern image of Yankees as timid traders.”

Blog Response Kofi Akan Brown

Whose Experience Matters?

Professor Susan Neiman has asked whether John Brown is a hero or a terrorist. John Brown was an American abolitionist (a person opposed to slavery) who lived from 1800-1859.

What is a hero? Professor Neiman defines hero as someone who is willing to have courage in the face of adversity to stand up for others. However, this definition is not clear. But even if it were, the definition of a hero is dependent upon the viewer. As Professor Neiman mentioned with Odysseus, despite being considered a hero, he was reviled by different audiences. A hero can be someone who does some immoral acts for a greater good. Or a hero might be a paragon of virtuous acts.

One trusted source for definitions is the Oxford Languages online. According to Oxford languages, a hero is defined as “a person who is admired for their courage, outstanding achievements, or noble qualities”[1]. Professor Neiman’s lecture focused on the “admired” criteria for a being hero. She mentions how Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson held him in high esteem- why the opinion of white philosophers themselves enmeshed in racist ideology should confirm Brown’s heroism is unclear, and William Lloyd Garrison, who was an abolitionist, admired John Brown. Some of John Brown’s adversaries, such as American Confederate General Stonewall Jackson, also admired Brown. Professor Neiman also mentions that former slave Fredrick Douglas admiring Brown.

Professor Neiman briefly talks about John Brown’s courage. She tells of how Brown participated in the Bleeding Kansas battle against American pro-slavery settlers in the state of Kansas. She also tells of how Brown faced his execution with calmness and encouraged his audience to continue the fight against slavery. He also refused to be rescued or tried for lunacy when given the opportunity to escape execution.

Regarding Brown’s courage, Professor Neiman does not adequately illustrate how Brown was willing to fight against slave masters and slave owning states. Slave owning states were places of constant fear. This was in part due to the occurrence of at least 250 slave rebellions[2] and the fact that the arbitrary killing of enslaved humans was legal. Under American chattel slavery African Americans were treated as property. Slave masters were allowed to rape enslaved men and women. Slave masters’ wives raped enslaved men.[3] Slave masters blamed the victims, whether male or female, for being raped.[4] Slave masters were legally allowed to torture and mutilate enslaved people.[5] If a slave master was suspected of fathering a child born to a slave, the child would still be enslaved. If the wife of a slave master and a male slave had a child, the child would either be sold or killed.[6]

Enslaved children were subjected to physical torture and sexual exploitation. Children were not allowed to use terms of endearment towards their parents. They were forced to eat from troughs like animals. Children would stand between a slave driver and the slave that the driver was beating with a whip, thus taking the beating for the victim. At other times children attacked slave drivers to protect another slave from being whipped.[7] In addition, slaves were not given proper clothing, food, or shelter which commonly led to sickness.[8] It was this environment that Brown willingly entered. Yet Neiman focusing on the heroic nature of Brown overlooks the immense courage that enslaved people or fugitives had to muster every day to survive in this environment- or more impressively, fight against it once freed and help others rather than delight in their individual freedom.

With reference to John Brown’s outstanding achievements, Professor Neiman asserts that the Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry may have been a catalyst for the American Civil War. The Civil War is recognized as ending American slavery, but the lecturer does not provide ample historical evidence to argue that Brown’s raid was its catalyst.

The lecture provided some examples of what might be considered John Brown’s noble qualities. It’s mentioned that he took care of sick children, risked his life to end slavery, treated children tenderly, and that he enjoyed admiring nature. However, are these examples enough to prove that Brown possessed noble qualities? I would also want to argue against the idea of nobleness- the decency in that phrase already excludes so many who suffer.

In looking at whether John Brown was a terrorist, a clear definition of terrorist is not posited. It’s stated that, according to the time, John Brown’s attack on Harper’s Ferry would be terrorism. However, if a different definition is used, terrorism is “the unofficial or unauthorized use of violence and intimidation in the pursuit of political aims”[9] John Brown’s raid was unlawful under United States law, which is why he was executed. He wanted to violently free slaves from slave owners, who were civilians. It can be argued that he did the raid in pursuit of political aims. This follows from Professor Neiman’s statement that Brown believed he was following the U.S. Declaration of Independence, which states that humans are equal. However, the Declaration refers to God given rights, which are human rights and not political rights. In addition, Professor Neiman states that John Brown wanted to implement his Christian belief in the equality of all humans, which is not a political aim. Consequently, the question remains as to whether John Brown was a terrorist considering the mixing of human rights and religious beliefs that led him supposedly more than political aims.

Professor Neiman makes the argument that John Brown was a hero. However, more background information should be offered to support her assessment more strongly and the question of who’s assessment of his character matters should enter into the equation. Overall, the lecture was thought provoking and illuminated aspects of John Brown’s character, and the time in which he lived, that may be unfamiliar to many people.

[1] Google Oxford English Dictionary Definition https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/86297?rskey=2TxXzM&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid

[2] Aptheker, Herbert “American Negro Slave Revolts” Science & Society. Vol. 1, No. 4 (Summer, 1937) https://www.jstor.org/stable/40399115?seq=15

[3] Foster, Thomas A. “The Sexual Abuse of Black Men under American Slavery” (September 2011) https://www.jstor.org/stable/41305880?seq=1

[4] [4] Spivey, William “The Truth About American Slave Breeding Farms” (June 9, 2019) https://medium.com/the-aambc-journal/the-truth-about-american-slave-breeding-farms-ee631e863e2c

[5] Fede, Andrew “Legitimized Violent Slave Abuse in the American South, 1619-1865: A Case Study of Law and Social Change in Six Southern States” https://www.jstor.org/stable/844931?seq=6

[6] Anon, Anon M. “Sexual Relations Between Elite White Women and Enslaved Men in the Antebellum South: A Socio-Historical Analysis” Inquires Vol 5 NO. 08 2013. http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/1674/sexual-relations-between-elite-white-women-and-enslaved-men-in-the-antebellum-south-a-socio-historical-analysis

[7] King, Wilma. “Within the Professional Household: Slave Children in the Antebellum South” The Historian. Vol. 59. No. 3 (Spring 1997). https://www.jstor.org/stable/24451949?seq=5

[8] Schwartz, Marie Jenkins. “Family Life in the slave Quarters: Survival Strategies” OAH Magazine of History. Vol. 15, No. 4, Family History (Summer, 2001). https://www.jstor.org/stable/25163462?seq=2

[9] Oxford English Dictionary. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/199608?redirectedFrom=terrorism#eid

Lecture Video & Q&A’s

Mr. K ofi A Brown

This blog was well written and brings Great thought , while most people do not even know who John Brown was or have forgotten about him totally! From your writings I Iook to John Brown as a servant of colored people. Again thank you for your insight and knowledge!

I fear that Kofi Akan Brown’s comment misunderstood much of my lecture. Perhaps he missed my first lecture in which I explained why I do not give definitions for contested concepts but choose to work with exemplars. He also seems to ignore the fact that I was asked to speak for no more than an hour, in which I could not possibly address all the subjects he raises. Providing ample historical information for the claim that Brown was the catalyst for the Civil War could not be done in the allotted time. I did, however, cite many authorities who do so, among them Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. Dubois, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Herman Melville, and many contemporary historians, the best of them being David Reynolds. For further information, however, I highly recommend W.E.B. Dubois’s short biography John Brown, from which I quoted during the lecture. – One thing I did not intend to address, however, was the evil of slavery. I, and all the figures I discussed, regard slavery as a very great evil. This is the starting point on which we all agree; the question of the lecture is what actions are justifiable in fighting it? I argued that Brown’s actions were justified, although many still contest this today.

Mr. Brown also asks why we should pay attention to the views of white philosophers who were enmeshed in racist ideology. I trust Mr. Brown would agree that it is desirable that racists become anti-racists, to use Ibram X. Kendi’s terminology. My point was to show how Emerson and Thoreau, who were enormously influential in their time, became anti-racists through the influence of John Brown and thereby influenced the rest of the country to support a war against slavery. Surely we should be interested in understanding how people change for the better and thereby create massive social change?

Finally, I am entirely puzzled by Mr. Brown’s desire to argue against the idea of nobleness. Perhaps he is conflating nobleness with nobility? History gives us thousands, if not millions of examples of noble suffering.