Dr Kirsty Murray: Networks, Nodes and Nuclei Connecting the Study of World Christianity

Networks, Nodes and Nuclei Connecting the Study of World Christianity.

Dr Kirsty Murray

Listening to another excellent Gifford lecture on Tuesday two reflections came to mind. One was the continuing aptness of the over arching theme of the series and the value of examining networks and nodes. There is a risk that the study of World Christianity becomes increasingly fragmented into bite-sized, depth studies with no effort to draw out the interconnections and comparisons of the broad picture. David Hempton’s lectures counteract that and draw on the increasing interest in South to South contact in the discipline.[1]

The prioritisation of particular physical and intellectual connections is often dependent upon where we stand in the world. I was reminded of the reorientation of geographical and intellectual space that occurred in the work of Pacific Islander scholar Epeli Hau’ofa (1939-2009). Chaffing under the constant description of Pacific Islanders as coming from small pockets of precarious population amidst a vast ocean, he overturned this outsider perspective and replaced it with one from the inside. He turned a portrayal of the Pacific Ocean as a place of isolation and dislocation to one of connection by coining the phrase “Our Sea of Islands.” In doing so he gave both a proud nod to the voyaging of the original settlers of his region and hoped to build strong bonds of cultural solidarity in his own time. Flipping the typical perspective on its head, he described the sea as being what brought the people together. He wrote:

Oceania is us. We are the sea, we are the ocean, we must wake up to this ancient truth and together use it to overturn hegemonic views that aim ultimately to confine us again, physically and psychologically, in tiny spaces that we have resisted accepting as our sole appointed places and from which we have recently liberated ourselves.[2]

He wanted people not to be defined by the smallness of their islands but by the opportunities of the great ocean of connection.

Tracing networks, then, is not just about identifying the organisations, individuals or media pathways along which religious ideas may have travelled. It should also entail reflection on how connection and distance were perceived and understood by multiple actors. The insider and the outsider may describe individual nodes and bonds as more or less significant. Local studies may reveal strong emotional investment in connections which seem insubstantial in another light. Perceptions of proximity and of distance, and of the very nature of networks, depend very much on where a person stands.

My second thought was prompted by the mention made on Tuesday, and at Wednesday’s seminar, of ideas travelling across the network in more than one direction. This has a strong resonance in the Pacific Islands. Scholars often extend the event of people, objects and ideas “crossing the beach” into a metaphor.[3] From the late eighteenth century there were examples of import and export. Encounters of trade but also exploitation. At times nothing or no one crossed the beach at all; there were also misunderstandings and skirmishes; and sometimes new uses and meanings were applied on “the other side”. It was not easy to predict what or who would make it across the sand. The beach was, and still is, crossed in different directions.

This leads me more directly to the focus on women in Lecture Five as I was reminded of the Pacific Islander women who accompanied husbands, who were designated as teachers and sometimes pastors. The converts of the nineteenth century became, often in less than a generation, missionaries to the next archipelago. They were representatives of an ever shifting network seeking out new landing places where they could found a mission themselves and pass on what they had received.

Woman to woman mission and the demonstration of Christian home life is a recurrent theme in missionary work down to the present day. The work of Samoan, Tongan and Fijian wives adds an additional layer of complexity when we examine cultural transmission networks. They carried not only nineteenth century Methodist, Congregationalist or Presbyterian ideals but also food stuffs from their home islands in Polynesia, house styles and textile or mat making techniques.[4] In the process they doubly transformed existing patterns of domestic labour and child rearing in Melanesia. Networks transmitted unanticipated content with ideas crossing beaches in ways that were never intended by missionary strategists in Europe or America.

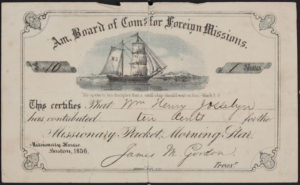

Meanwhile, British and American children collected pennies or ten cents for mission ships for Polynesia and Melanesia. Each child may have made only a small financial contribution but through their efforts they had a sense of direct participation in the network. They belonged to a religious culture which valorised the sharing the “good news” and dramatized the exploits of the missionaries who traversed the wide Ocean. The collection boxes, certificates and missionary publications were designed to give the child contributors a sense of sharing in the adventure.

Certificate given to a child for a 10 cent donation to the ABCFM.[5]

European or American missionaries were often the role models gifted to children in their Sunday School Prize books but there were also stories about model convert children from the Islands. For example, Laku, a young women from the New Hebrides portrayed in Heralds of the Dawn (1924) as being transformed from a “wild and giddy girl” to a Presbyterian communicant, able cook and suitable wife for a native pastor.[6] These stories that were passed back across the beach simultaneously shaped racialised and colonial perceptions of the Pacific Islands and were an attempt to foster a shared sense of Christian values and community.

It is the potential for drawing out the complexity of relationships and nuance of perspectives that has made these Gifford Lectures so thought provoking. The multiple branches of Christian networks have bounced ideas across the globe and back again; at times crossing and re-crossing beaches. This could result in distortion and misunderstandings yet also in perceptions of connection and sharing of common Christian values.

Kirsty Murray is a historian and her main interest is the relationship between religion and popular culture. She began her role as a Teaching Fellow at the University of Edinburgh in 2001 and her research has been in the transmisison of Christianity in the Pacific Islands, the history of Methodist Mission, and she also has an interest in gender and popular religiosity in Early Modern Europe.

[1] David Maxwell, “Historical Perspectives on Christianity Worldwide: Connections, Comparisons and Consciousness” in Cabrita, Joel, David Maxwell, and Emma Wild-Wood eds. Relocating World Christianity : Interdisciplinary Studies in Universal and Local Expressions of the Christian Faith (Brill, 2017)

[2]Epeli Hau’ofa, We are the Ocean, Selected Works (University of Hawaii Press, 2008) p39.

[3] Greg Dening. Islands and Beaches: Discourse on a Silent Land—Marquesas, 1774–1880. (University Press of Hawaii. 1980)

[4] Sione Latukefu, “Pacific Islander Missionaries” in The Covenant Makers: Islander Missionaries in the Pacific ed. Doug Munro and Andrew Thornley (Pacific Theological College, Fiji, 1996) 33-34.

[5] Image Source: Historic New England website: “This is a certificate for 1 share in the first Morning Star Missionary Ship. The Morning Star was a missionary packet sent to the Sandwich Islands, now known as the Hawaiian Islands. This certificate was issued to my father William Henry Josselyn when a boy seven year of age.” https://www.historicnewengland.org/explore/collections-access/capobject/?refd=EP001.01.024.01.01.006 Accessed 13/10/21.

[6] Heralds of the Dawn: Early Converts in the New Hebrides, William Gunn and Mrs Gunn (1924) p146-9.

Recent comments