Lecture 1: Towards a Theory of Transnational Religious Change

This evening commenced the first of our 2021 Gifford Lecture Series. Professor David Hempton from Harvard Divinity School opened our lecture recollecting fond memories of Edinburgh- namely beating us in a hockey game whilst studying for his PhD in St Andrews. What follows here is a summary of this first lecture, the video recording for those who wish to re-visit or catch up, and a response given by Axolile Qina, a 3rd year PhD student in New Testament and Christian Origins from South Africa, studying in New College, University of Edinburgh.

‘[a]n overconcentration on conventional structures in the history of Christianity, whether hierarchical, national, denominational, or theological has obscured the efficacy of human action and the dynamics of change, especially change from below and change that cannot easily be tracked through traditional sources.’

It seems fitting to begin this summary with a section from Professor Hempton’s conclusion that clearly demonstrates his motivation for these Gifford lectures. His methodology of examining the history of Christianity from 1500-2020 (surely not a daunting task for any historian) through Networks, Nodes and Nuclei, is not designed to create a new theoretical framework. Instead, Hempton’s aim is to show how fluidity, encounter and connectivity, not unlike the evolutionary processes of nature, is a vital component in the study of the history of Christianity that complexifies, expands and deepens our understanding.

To illustrate the meaning of Networks Hempton uses the metaphor of the complex underground resource-sharing network of thread-like fungi, called mycorrhizae, in tree roots. ‘Younger trees benefit from more mature trees and different species symbiotically share an ecosystem which allows all of them to withstand stress, drought and other destructive events.’ Religious Networks therefore, in a working definition, ‘is a group or system of interconnected people, ideas or spaces designed to achieve a religious purpose beyond the confines of existing borders and boundaries established by states, hierarchies, or religious traditions.’

The interconnectedness of networks make them distinct from movements, yet their mobility separate them from institutions, though of course networks can eventually evolve into either. Part of the genius of the underground tree root metaphor is the emphasis on the symbiotic relationship between the trees. The historian needs to take symbiosis seriously when studying the encounters of people, cultures and epistemologies in the global expansion of Christianity. A PhD graduate of Hempton, Helen Kim, illustrates this with their dissertation, entitled ‘Gospel of the “Orient”: Koreans, Race and the Transpacific Rise of American Evangelicalism in the Cold War Era.’ Kim argues that the rise of evangelical voluntary societies in Korea at the end of the Cold War period were connected movements. Additionally, these networks created in South Korea actually refashioned American fundamentalism into mainstream evangelicalism.

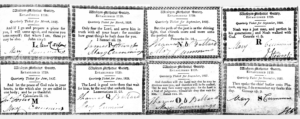

Not only is the encounter between religious networks significant, but also the meeting of the religious network and the social atmosphere of the time. This is vital, according to Hempton, believing that often the environment is just as crucial as the idea, the Network acting almost ‘parasitically’ on social changes. A great illustration was given in the question answer session where Hempton recorded how Methodism as a Network bypassed the parish structure of Anglican churches. The voluntary association model, with a ticket system, was attractive for the social changes of the day. Today, this model is less successful, with the self-constructed medium of the website and the ‘spiritual but not religious’ non-belonging identity taking centre stage. Hempton clarifies that, ‘networks are mostly sustained by flows of information, personnel, and images, but these flows are not unidirectional, nor do they remain unchanged as they move from centres to peripheries and also in reverse.’

Nodes refer to a point where lines or pathways intersect. Or, as in nature, the point of a plant stem where two or more leaves emerge. For our purposes, nodes refer to ‘places where people, ideas, and movements intersect and produce something different or more fertile.’ There are obvious places that fit this description- universities, diverse cities, media hubs and historic events such as the Council of Trent or the Hampton Court Conference (it made me think of the Edinburgh 1910 World Missionary Conference), but there are other, more significant haphazard, or even perhaps accidental nodal points too. The introduction of Hempton’s lecture referred to the Azusa Street Revival or later, to the regional nodes of the 500 or so shrines erected in New Spain, demonstrating the piety of the indigenous believers often at odds with the Iberian Catholic central power. The latter category, to me, also emphasize the gradual emergence of these nodes- often build through long term encounters or relationships rather than fundamental, one-time moments. Nodes, of course, are not only significant for Christianity. Hempton illustrated the importance of the early Islamic pilgrimage routes across Saharan Africa to the Middle East and Singapore as a node of Sufi networks for understanding the transnational circulation of people, ideas and literature.

Finally, Nuclei. Classically, the controlling genetic code of an organism, the positively charged center of an atom. Here, the ‘very heart of a group or a movement.’ What gives these groups the energy, or optimism, to successful inspire and grow? For Methodism, Hempton believes the ‘strong optimistic belief in the achievement of personal and social holiness on earth as in heaven’ motivated its rapid transnational growth. This more theological section he left on a cliff hanger, pointing towards future lectures where he will explore similar questions about the Protestant Reformation, the Jesuit Order, Latino Catholicism, evangelicalism, fundamentalism, and Pentecostalism.

So we see how the model of Networks, Nodes and Nuclei allow us to analyze connectivity and the consequences of encounter in the history of Christianity. Though the methodology comes with a word of caution that tis cannot be only the disciplinary method. Hempton draws attention to Kate Davison’s work who shows that network analysis ‘can easily be based on anachronistic categories, may privilege progress and achievement, possibly favor social scientific models, and depend upon bigger data sets which in turn prioritize the availability of such data in the Eurocentric world.’ Though in his last examples, focusing on networks of religious migration, Hempton convincingly shows how this methodology can open up new horizons of understanding. Fittingly for our moment of commemorating Edinburgh’s great Andrew Walls, Hempton draws us into the nodal point of Sierra Leone, a ‘British imperial model for converting Africa to Christianity.’

Sierra Leone encountered a network of freed slaves, who migrated from the American colonies to Canada, before returning to Africa through Sierra Leone. Here, the intersection of traditional ‘elite’ missionary religion was faced with populist black spirituality, having profound implications for the mission to the continent. Finally, this method also allows us to focus in our complex human social identities. Using the work of cultural anthropologist Todne Thomas, Hempton shares how the Plymouth Brethren movement, birthed in Britain in the 1820’s and 1830’s came a framework of belonging to two churches, one an Afro-Caribbean majority and African American minority and the other the opposite of these groups. Thomas writes that, ‘church members understand themselves to be part of trans-local networks of sister churches that are linked by their own migration histories’ and Hempton concludes that ‘the ‘lived religion’ of ordinary Black Christians is more vigorously brought to life in all its rich complexity than any explanation based on preconceived and reductive notions of the Black church, evangelical Christianity, and heteronormative constructions of families.’

Our first introductory lecture has already taken us to opposite ends of our globe through stimulating case studies to illustrate the usefulness of study the history of Christianity through networks, nodes and nuclei. The next lecture is entitled ‘Religious Networks in the Reformation Era’ where firstly, a deeper theoretical analysis will greet us before exploring the printing networks that greatly boosted the Lutheran Reformation. Alongside, the Jesuit Order and their great network of schools and colleges will be explored.

Response to Lecture 1

Religious Mobility and The Creation of Transnational Kinship: Networks, Nodes, and Nucleus

Towards a Theory of Transnational Religious Change presents a case for a creative and dynamic approach of engaging religious change within history. The dogmatic and denominational focus of researching Christianity, which narrowly looks at its development between 1500 and 2020 by only prioritising the impact of Enlightenment in the West and the Reformation, limits the intersectional nature and development of this faith within the various social contexts in our Global world. This is what I think Professor David Hempton contends and challenges us to consider in his first Gilford lecture. Hempton proposes this by first discussing how Methodism was a ‘highly mobile religious network’ that transcended its identity as a religious society in connection with John Wesley in Britain, and included members to as far as the Caribbean islands and Australasia. What was fascinating for me with this point is the way religion can seemingly have mobility, to the point where it is able to adapt or even utilise its influence within changing social circumstances for its own benefit. This mobility, at least according to Hempton, can be evaluated in his three ‘framing words’: networks, nodes, and nucleus. Additionally, these three aspects are applied in a case study, which introduces the notion of ‘Kinship making.’ This idea has resonance depends on already existing cultural structures, which supports Hemptons view on how: ‘successful religious networks depend on pre-existing structures or social conditions that facilitate their transmission.’

Hempton’s working definition of a religious network as: ‘a group or systems of interconnected people, ideas, or spaces designed to achieve a religious purpose beyond the confines of its borders and boundaries established by states, hierarchies, and religious tradition.’ Here, Hempton uses the ‘networks’ as a ‘primary metaphor’ and ‘tool of analysis’ in order to understand religious mobility. Such an approach allows for flexibility, whereby, a religious movement is assessed for its innovation, instead of, limiting the study to a rigid structure of ‘denominations, countries and organisational hierarchies.’ Nodes, on the other hand, ‘are places where people, ideas, and movements intersect and produce something different or more fertile.’ This can include spaces like university, cities and town centres, centres of trade and social media. Lastly then, nucleus ‘is the positively charged centre of an atom or the very heart of a group or a movement.’ In other words, the nucleus is the focal point that holds a religious network together. For example, Hempton reflects on the research of his doctoral students, Helen Kim, who argues that the rapid rise of voluntary evangelical movements in Korea after the Cold War were interconnected and forged alliances beyond its borders.

The transnational partnerships with South Korea and American fundamentalist movements in the form of ‘para-churches’ gave rise to the: World Vision, Campus Crusade, and the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association. Hempton contends here that the backdrop of the Cold War allowed for the development of anti-communism ideology, which paved the way for American evangelism to have influence in South Korea and Korean Protestants benefitting for their own advantage. This included a pro-American capitalist belief that went against communist Chinese and Soviet states. Such a reading of social history in the study of religion, displays the nuances, intersectionality and relationships of power at play within a context. Another example of a religious network that stretched beyond its borders is the Redeemed Christian Church of God. Hempton rightly points out that its ‘main hub’ is located in Lagos, Nigeria, but has a transnational network that utilised nodes of social media and grew its financial power globally, by including other spaces of worship in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean, and even a ‘redemption’ campus in Dallas, Texas, USA.

After providing an overview of the strength and weaknesses of his argument, and discussing what areas that he will cover in his other lectures of this Gilford series, Prof Hempton provides a test case to assess his three n’s: networks, nodes, and nucleus, as way of conclusion. This is based on the work of the cultural anthropologist, Todne Thomas, who performed ethnographic research of two Africana congregations that compromise of African-Americans and Afro-Caribbean, called: Dixon Bible Chapel and Corinthian Bible Chapel. The research discovered how the DNA or nucleus of these churches are rooted in a “Kincraft” or ‘kinship making,’ which ironically transcends ethnic nationalities through a creation of followers understanding themselves as being part of a Global family of God. This for me, has resonance with African religious family systems, whereby, ancestors and humans live in a symbiotic relationship that is cosmologically related to both physical and spiritual realms.

As Hempton points out, ‘church members constructs a sense of belonging to a broad kinship collectives (e.g., transnational diasporized family networks, family of God) through imaginaries that are not just not just distant and aspirational but also deeply meaningful and personal.’ I would suggest that this ‘family of God’ as a transnational network has resonance with the ways that we Africans relate our human community physically in relation to, not only their immediate family (parents and siblings), but also, with the clan (cousins, aunts/uncles, and grandparents), whom constitute as singular family unit that is bound to our ancestor (previous descendants of the clan who are no longer alive in the physical realm). Although, Hempton showcases the migration significance of these family centred communities, the adoption of this transnational network that comprises of diasporic Africans, supports the view that these religious movements truly depend on pre-existing structures, whether consciously or unconsciously, by those pioneering them to move beyond their specific location. This is important to consider in our technological age of globalisation, as it seems kinship is now being created through shared ideological nodes or nucleus that bind people together, which goes beyond blood, nationality, and ethnicities. A social history into Christianity using this framework can expose these nuances and make connections with existing cultural system that are present even in our time today.

Video recording

Join the conversation by posting a comment below. Instructions here.

Recent comments