Lecture Two: What Makes Us Human? The Construction of the Human Niche and the Capacity for Belief

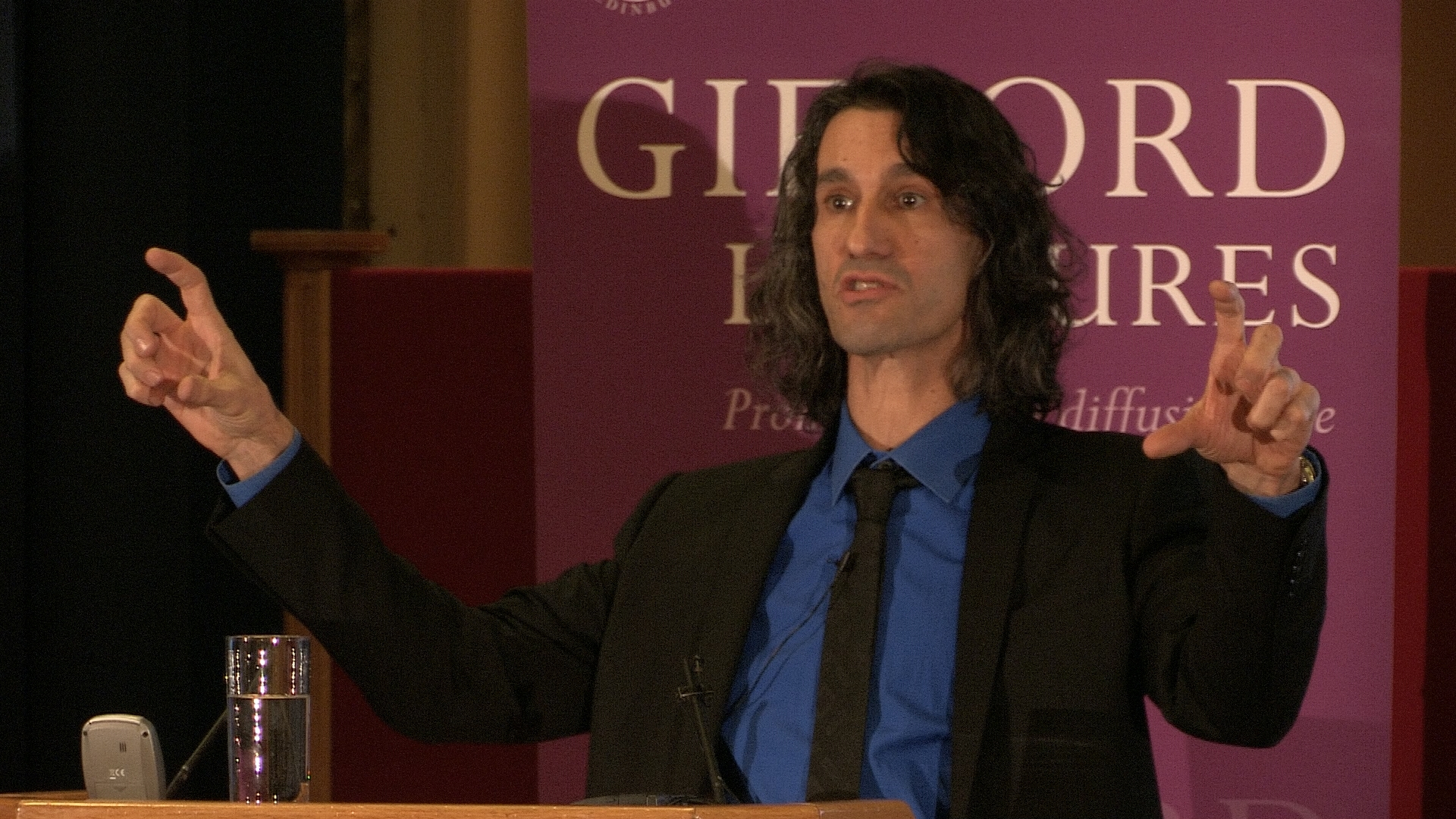

In this second lecture Professor Agustin Fuentes focuses on the human niche as it relates to our capacity for belief. The video of Fuentes’ lecture is embedded below for those who were unable to attend in person, or for those who’d like to watch it again. An audio only version can also be found at the end of this post. In order to further facilitate discussion Dr Mikael Leidenhag and Katherine Chow will be adding their initial reflections on Professor Fuentes’ lecture. Leidenhag earned his PhD in Philosophy of Religion from Uppsala University (Sweden) and is currently a Research Fellow (Templeton Foundation) in Theology and Science at the University of Edinburgh. Chow is currently a Postgraduate Research Student working in the field of Political Theology at the University of Edinburgh. We’d like to reiterate that we warmly welcome anyone wishing to engage with Fuentes’ lectures to contribute their comments and questions below.

In his second lecture Feuntes set out to answer “What makes us human?” by inquiring into the construction of the human niche and our capacity for belief. He began his story approximately 2 million years ago with our ancestors who, despite their meager sticks and stones, were able to survive in an environment full of bigger predators and were able to successfully find food and shelter amidst widespread competition. As he stated, “they survived, changed, expanded, and eventually became us, one of the most widespread and significant species on the planet. And in this history, in this process, lies a key answer to why we believe.” How did they do this and why is this significant for understanding why we humans believe? As Fuentes stated up front, “In a nutshell, they cooperated, innovated, created, imagined, and eventually believed. They became human. And in the process constructed, and were shaped by, a dynamic new niche, a new way of becoming in the world.” Fuentes asserted that understanding this evolutionary history is a key component for understanding why we humans believe.

Fuentes went on to speak about what makes a human a human. As he said we are mammals, primates, and hominins “but we are also something distinct from all of these categories.” He spoke about how humans can philosophize, experience existential crisis, and speak and experience various transcendent components of life. An evolutionary explanation of what makes us human, he affirmed, ought to be compatible with these aspects of human existence even though these aspects of humanity are often the focus of philosophers and theologians. Without necessarily competing with philosophical and theological descriptions, an evolutionary description of what makes us human needs to undertake its inquiry in its own distinctive way. As he stated, “An evolutionary description of distinction has to be a measurable or otherwise discreetly identifiable set of parameters that classify one cluster of beings versus another.” He then went on to ask, “what makes us human in the evolutionary sense?”

He began his answer by stating that it has to be “more than a constellation of morphological traits or genetic sequences.” The identity of living organisms, he affirmed, is constituted not only by what they are made of, but also by what living organisms do. As he stated, “an evolutionary definition needs to encompass not just an organism’s materiality (morphology, genetics, etc.) but also its behavior, its way of relating to the world.” However, as he went on to affirm, surface level descriptions of behavior and a recognition of complex sociality are not sufficient for understanding the distinctiveness of humans. As he said engaging with Jacob von Uexküll’s work, “to understand, from an evolutionary perspective, what makes a particular kind of organism distinctive, what makes it ‘it’ we need to know not just its form and some details of its behavior, but also the way that it exist in, and with, the world. . . . We need to be able to describe its umwelt, the way it perceives and experiences the world.”

It is here that Fuentes, from his own evolutionary perspective and in his own distinctive way, begins to describe the “human niche” in a way that offers interesting interdisciplinary possibilities of convergence with two previous Gifford lecturers. Namely, philosophically, with Paul Ricoeur’s Oneself as Another (originally delivered here at the University of Edinburgh in 1985) with his, among other things, emphasis on narrative identity and, theologically, with Rowan Williams’ The Edge of Words (originally delivered here at the University of Edinburgh in 2013) with his, among other things, discussion of the formation of personal identity through the ongoing action (especially that of speech, holistically understood) of embodied persons with one another.

As Fuentes went on to describe the human niche, “in contemporary ecological and evolutionary parlance, we use the term niche when describing, scientifically, the umwelt of an organism.” Niches or life-worlds, as Fuentes described, are dynamic not static. They consist of potentialities for continued development. Fuentes asserted that understanding the human niche is essential for a satisfactory answer to what makes us human. Fuentes initially went on to describe the human niche “as the spatial, ecological and social sphere that includes all social partners, perceptual contexts, and ecologies of human individuals, groups, and communities and the many other species that live with and alongside humans.” It is, in short, “the context for the lived experience of humans and their communities.” He then went on to describe in further detail the multifarious aspects of the human niche in conversation with the anthropologists Terry Deacon and Polly Weissner and with the biologist Kevin Laland. Concerning the latter’s work Fuentes stated that “if what makes us human is, in part, creating, occupying and modifying the human niche, and co-constructing and co-evolving with it, then a large part of the answer to ‘what makes us human?’, and therefore a substrative component of why we believe, lies in the patterns and events that characterized this process across the longue durée of our evolutionary history.” What we do and have done, and who we do and have done it with, is an essential component for answering what and who humans are and why we humans believe. As Fuentes went on to state, “The capacity for belief emerged during the evolution of the human niche.”

Fuentes then went on to speak further about how we got from the early Homo to the human niche. He discussed the development of bodies over the past 1 million years, but then stated that “bodies are not all that matter in this narrative.” He went on to claim that the human success story “is linked directly to the emergence and development of a distinctive human niche, a novel umwelt, in which the capacity for belief emerges.” He then went on to narrate the development of the human niche starting when it began to pick up pace in the last 3-4000,00 years ago, began dramatically expanding 125,000 years ago, and then when it began “exploding in complexity over the last 12,000” years. As he stated, “This dynamic mode of becoming in the world forms the central core of our capacity for being human, for creating, for destroying, for imagining, and for believing.”

He then went on to divide this developing phase of the human niche (for the purposes of these lectures) into two parts: its initiation and its construction (but not completion).

In talking about its initiation he again returned to the work of Kevin Laland to highlight the co-constructive dimension of this initiation. He also highlighted the work of Matt Grove and Fiona Coward to illustrate the complexity of this initiation. For the purposes of his lectures Fuentes focused on a few key patterns. As he summarized, “the initiation of the human niche emerged from the interfaces of physical ecological and behavioral mutual re-shaping process that came about when a tool making hominin, with increased social collaborative and communicative skills began to diversity their diets, reduce the pressures of predation on themselves, and work together to care for, and socially inculcate the young in more intensive and information-rich manners.” He highlighted the social and cooperative dimensions that allowed our ancestors to better collaborate through the sharing of information and the manipulation of materials in order to “create new solutions to the challenges of the world.”

In beginning to speak about the ongoing construction of the human niche (and not merely its initiation) Fuentes began to speak about the migration of our lineage across much of Africa, Eurasia, and East and Southeast Asia (between 1.8 million and 100,000 years ago), to Australia (by 15-20,00 thousand years ago), and to the Americas (by about 2,000 years ago). Fuentes often highlighted throughout the lecture a unique homogeneity despite widespread diffusion across the globe. Here he spoke of the development of and innovations in movement and group connections, and of the developments with “foraging, fire, meaning making (semiosis), and increasingly complex tools.” He went on to suggest that all these factors shaped “Homo cognition and social organization” that went in to constructing the human niche, which provided “the infrastructure for our capacity to believe.”

Fuentes went on to discuss the importance of the development of stone tool technology. He alluded to recent work by Dietrich Stout, the Laland lab in St Andrews, Michael Arbib and others to talk about the important links between the development of stone tool technology and the development of “the capacity for flexibility in behavior, diet and habitat manipulation” as well as a link to the development of stone tool technology that helped “facilitate novel connectivities across neurobiological systems” which played a role in brain development and the capacity for language. Fuentes then went on to note that by 200-400,00 years ago tools began to exhibit “regional and structural variation” as well as increasing complexity. The genus Homo by this time, he pointed out, “is locked into a life-way that ubiquitously involves the extensive collection and deployment of materials that we shape, meld to our desires and use to alter the world.” He then briefly went on to speak about extended cognition and suggested that it is not quite as distinctive to our technological age as some might think. The transportation of materials from one region to another also began to pick up during this period, indicating that trade among disparate groups was beginning to emerge. As he stated, “The contemporary patterns of deep interconnectedness, and exchange of ideas, between human groups across space, critical for the later development of belief systems, emerges here.”

It is here too that developments in “cooperative parenting” took place where “heightened compassion and caretaking” began to further develop in the human niche. Fuentes here engaged with the work of archeologist Penny Spikins to illustrate evidence of various forms of care and compassion in the genus Homo. While Fuentes did not sidestep the fact that violence and cruelty was also taking place he stated that “No other species, to our knowledge, exhibits such a patterns of care for others who are injured or ill aged.” Given this Fuentes went on to further claim that “this capacity, and its use, is argued to be one of the key reasons why members of our genus were able to spread so widely, across so many new environments, and collaborate so effectively as to develop a range of novel ways of reshaping the world around them.”

Fuentes then went on to highlight that the recognition of the power of fire was one of the most crucial factors in the construction of the human niche. As he stated, “fire as a tool, fire as light, and fire as external source of heat reshaped our niche and opened up new pathways and opportunities for social and cognitive interactions, inspiration of the imagination, and for the expansion into, and manipulation, of the world.” He then moved on to talk about the significant development of art and symbol: The “creation and use of materials that have meaning based in some shared ideology/assumptions/imaginations that are not necessarily tied to the material features/qualities of the item itself.” Fuentes went on to speak of the work that he and biological anthropologist Marc Kissel recently completed compiling all the “potentially ‘symbolic’ or meaning-laden artifacts in the early archeological record.” He suggested that “altering the world not just to serve specific functional ends, but to represent shared ideas and imaginaries” became a central component of the human niche. He then engaged with Terry Deacon to point to the omnipresence of meaning in the human niche, and suggested that this dimension of the human niche “is critical infrastructure for our capacity to believe.”

Fuentes began to end his second lecture by reminding us of the “core process that emerged” as part of the complex and multifarious nature of the human niche as it related to the initial question of why we believe. Firstly, he asserted, that it “set up the necessary biological, social and ecological infrastructure for a capacity for belief.” Secondly, it “set up the critical material and demographic infrastructure necessary for the development of particular kinds of ecologies and societies that enabled shared beliefs, and eventually belief systems, to emerge.”

He went on to reiterate the importance of the “increasing ubiquity of meaning making” that linked with the development of innovation and imagination and of the emergence of “imagining novel items/representations/materials” in order to create anew or to creatively modify. He also highlighted the important development of “the capacity for creating explanations of observable phenomena (such as death, the behavior of other animals, weather, the sun and mon, etc.).” He ended by stating that by 25,000 years ago the human niche was well constructed, but that it lacked some important “structural, ecological, and perceptual aspects” that shape how and why contemporary humans believe. And he promised to tackle those aspects in his next lecture.

Towards the very end of his lecture Fuentes’ claimed that “the capacity for belief is not simply an ‘emergent property’ of humanity or something ephemeral floating above the material ‘reality’ of the human.” This claim is something that Mikael Leidenhag would like to further reflect on as he gets our conversation on Fuentes’ second lecture started.

In his seminal book The Selfish Gene (1976), Richard Dawkins famously stated that human beings are selfish survival machines. On this rather gloomy picture, we are ultimately controlled, determined, and constructed by genes. Hence, the base structure of evolution, the driving force of evolutionary development, and human behaviour can be fully explained at the genetic level. The message is clear: genes run the show. This “genocentrism”, as philosopher Evan Thompson dubbed it, has been widely discussed and heavily critiqued. First of all, Dawkins’ theory seems to invite a problematic and scientifically strange dualism between genes and the rest of the biological environment. Second, this one-sided focus on genes means that we neglect other important evolutionary factors. One such significant factor is cooperation.

I want to thank Professor Agustín Fuentes for demonstrating the relevance of cooperation for understanding not only evolutionary development, but also human distinctiveness. As Fuentes shows, our quest for understanding human nature is intrinsically bound up with the biological phenomenon of cooperation. Our ancestors succeeded because “they cooperated, innovated, created, imagined, and eventually believed”. In order to understand what it means to be human it is not enough to simply count human capacities or provide a detailed list of morphological facts (although such a task can be important). Instead, we have to begin with a basic phenomenological fact of human creatures: we are experiencing beings that perceive, act, and react in the world in markedly distinct ways. This is one important insight missing in a genocentric portrayal of human becoming.

I greatly appreciate Fuentes turn to semiotics at this point, and his fusing of Jakob von Uexküll’s theory of umwelt with the scientific notion of niche. A human niche is, simply put, the life-world of an organism. This forms the basis for not only the capacity for human belief, but for the emergence of shared beliefs. More so, it provides the ingredients for cooperation between individuals and within larger communities. Fuentes, therefore, takes us away from a more reductionist understanding of evolution and a genocentric understanding of human behaviour. In this way, cooperation is not some strange anomaly to be explained away in terms of other underlying factors. Rather, it is a natural part of the human niche and grounded in the human capacity for belief.

But, how should we explain the emergence of the capacity for belief and how can it be safeguarded from the “acid of reductionism” (to quote philosopher Daniel Dennett)? Keeping with a semiotic view of human experiencing, he reminds us that human activity is not reducible to genetic facts. Fuentes, however, is careful to point out that this does not mean that the complex capacity for belief is “an ‘emergent property’ of humanity or something ephemeral floating above the material ‘reality’ of the human.” It is obvious that Fuentes does not want to land in a problematic dualism, like the one we find in Dawkins’ genocetric view of evolution. Fuentes wants to tread the golden path between reductionism and dualism, but I struggle to understand this middle path. He suggests that the capacity for belief, in a similar way to fingers and arms, has emerged to allow us to navigate and shape the world and to engage in our human niche. It is a core aspect of what it means to be human. However, this offered analogy, although interesting, does not seem sufficient for safeguarding this very important human niche from the reductive spell. Fuentes might successfully avoid a dualistic understanding of human experiencing, but I worry that his analogy might pave way for a reductionist understanding of human belief-forming. It is not clear, at least not at this point, how this view of the capacity for beliefs goes above and beyond standard evolutionary reductionism.

That being said, I greatly appreciate Fuentes’ emphasis on the particularity and distinctiveness of human experiencing and engagement with the world. I look forward to hearing Professor Fuentes speak more about the emergence of beliefs, and to help us unpack the distinctiveness of the human umwelt.

I should confess at the outset that I am not a scientist—not even a social scientist—but a student steeped in the humanities. That is to say, I spent my undergraduate years reading Plato, Augustine, and Rawls (a lot of Rawls, actually, maybe too much) rather than Darwin. The following response will probably reflect this. Social/scientists, please bear with me.

Trained in political theory and moral philosophy, I am inclined to bring everything into the realm of the normative. It is unsurprising, then, that I wandered out of the hallowed halls of the Playfair Library after the lecture pondering one main question: what are the implications of Professor Agustín Fuentes’s account of the human niche for moral philosophy?

This question was inspired by Fuentes’s compelling description of two capacities that he identifies as uniquely human: the capacity to imagine novel items, representations, materials, and either making them or altering other things to become them, and the capacity to create explanations for things. These capacities are indeed exciting ones. The lecture focused on the earliest manifestations of these capacities in the form of stone tools and early cave drawings. Yet one quickly realizes that the same capacities that allowed us to make stone tools and cave drawings have evolved to enable the creation of wildly sophisticated technologies and rich libraries of literature and arts.

In fact, many moral philosophers would seem to agree with this sentiment. There has been a trend in moral philosophy—found in the writings of Cicero, Immanuel Kant, John Rawls, among many others—to ground some notion of human dignity in particular capacities identified to be uniquely human. The capacities identified as dignity-grounding by moral philosophers are loosely related to the ones Fuentes identifies, such as rationality, moral reasoning, creativity, and personal agency (Incidentally, Jeremy Waldron offers a pretty good overview of these arguments in moral philosophy in his 2015 Gifford Lectures).

The obvious objection (articulated by thinkers including the famous philosopher-theologian Nicholas Wolterstorff) to an approach that seeks to ground human dignity in the identification of specific capacities perceived to be “uniquely human” is that such an approach risks being exclusive. Those who may be affected by illness or handicap, and as a result lack the capacities identified by moral philosophers, may come to be seen as less than “human.” This gestures to a certain danger in glorifying human capacities, impressive as they are.

This is why I found Fuentes’s holistic description at the beginning of this lecture of the human niche, which transcends morphological characteristics, so captivating. I especially liked the idea that what it means to know what makes a thing that particular thing has something to do with “the way in which it exists in, and with the world.” I can’t say I have anything particularly intelligent to say on this yet, except that it may be interesting to contemplate this ecological conception of a “human niche” in theological terms…

Of course, this is all the product of my own wandering mind, rather than a critique of Fuentes’s fascinating lecture. Fuentes himself steered clear of making normative judgments in his description of the human niche (and, as he notes in response to my question at the end of the lecture, he does so intentionally). Yet, in my defence, I wonder if it might be a good idea to consistently contemplate the normative alongside the descriptive. Granted, it may not be possible to link the descriptive directly to the normative (I suspect our famous alumnus David Hume may agree with this assessment), but I would argue that the ethical should never be too far from our minds. Certainly, the work cannot all be done by one person. More than anything else, then, maybe this is a call for scholars to work across disciplines to collectively figure out what on earth human existence is all about.

Is it allowable to say that mind transcends brain? Dawkins is close minded in his atheism. Consciousness matters. Science and materialism have their limitations.

I find the concept of linking our ancestors earliest practical challenges to the initiation of language and discription for passing on skills, turning into perhaps story telling, and wishing and hoping collectively, with faith and beliefs both absolutely tantalising and hopeful.

Beliefs had to have begun somehow, and I’m really excited to hear Prof. Fuentes’ theories.

The stage has been set to really deeply explore the connection, can theology and anthropology find some common ground through the ever expanding realms of research? Is that even something that we should be exploring? Well it is almost impossible for us not to, because that is so much of what it is to be human, as Prof. Fuentes has shown in his first two lectures. As a species we have the incredible morphology and intelligence to ask questions and to be endlessly diligent in trying to find answers and solutions that satisfy us until they no longer do. The wheel probably began as a long rolling log, until some thinker dreamed of an novel new concept which probably seemed like madness to most.

I wish I had studied theology, so that I could be more equipped to link the two perspectives in my own mind. I think that these lectures will inspire me to do so.

Thank you so much Professor Fuentes.

I find the concept of linking our ancestors earliest practical challenges to the initiation of language and discription for passing on skills, turning into perhaps story telling, and wishing and hoping collectively, with faith and beliefs both absolutely tantalising and hopeful.

Beliefs had to have begun somehow, and I’m really excited to hear Prof. Fuentes theories.

The stage has been perfectly set to really deeply explore the connection. Can theology and anthropology find some common ground through the ever expanding realms of research? Is that even something that we should be exploring? Well it is almost impossible for us not to, because that is so much of what it is to be human, as Prof. Fuentes has shown in his first two lectures. As a species we have the incredible morphology and intelligence to ask questions and to be endlessly diligent in trying to find answers and solutions that satisfy us until they no longer do. The wheel probably began as a long rolling log, until some thinker dreamed of an novel new concept which probably seemed like madness to most.

I wish I had studied theology, so that I could be more equipped to link the two perspectives in my own mind. I think that these lectures will inspire me to so.

Thank you so much Professor Fuentes.