Why nature and nurture matter when it comes to our health

Is it nature or nurture that affects our health? Usually it’s both.

Generation Scotland tackles important questions about health risk. What matters most: nature (genetic and biological factors) or nurture (environmental and social factors)? With rare exceptions, the evidence almost always points to a combination of both. Here’s why.

Some medical conditions really are only down to genetics. We know of about 5,000 different examples. Most are vanishingly rare, affecting just a handful of babies born each year. In each case, the faulty gene is the dominant factor. The identifying features are only ever seen when accompanied by the specific gene fault. If we add all 5,000 up, they affect about one in a hundred babies born each year in the UK.

What about the other conditions that affect our health and run in families? Health risks are not evenly spread. Each family has its own genetic and medical history. That’s why Generation Scotland is a family-based study. No two families are quite the same. If we look back in time and to more distant relatives, there are often medical conditions that pop up more often than by chance alone. It might be asthma or diabetes, heart disease or bowel cancer, depression or dementia, or any of a long list of conditions. However, in none of these examples is there a clear and obvious genetic ‘smoking gun’. The increased risk comes from many different gene variants. Each changes the risk by a tiny fraction. Add them all up and it can make an important difference.

For these conditions, the environment matters too. Indeed, our health is heavily influenced by nurture – where, when and how we are born, brought up, and live our lives. People’s health also changes over time and varies from country to country. Things like health services, infection control, education, housing, wealth, pollution, diet and exercise all play a part.

We now know just how damaging smoking is to our health.

By contrast, it is now easy to detect differences in the genetic makeup between any two individuals. If we compare all individuals in Generation Scotland with a particular condition (‘cases’) with those that don’t have it (‘controls’), we can see if any gene variants keep appearing in the cases. This type of research is going on all around the world. Generation Scotland is helping the search by sharing what we have found. If two or more different studies find the same thing, we can be more confident that we are on the right track.

A good example would be the work we led on defining a set of over 100 genetic factors that influence the risk of depression. Some made immediate biological sense. They were genes known to be important for how the brain functions and antidepressants act. In some ways, the more interesting findings were genes with no known previous connection. These provide new clues and a start point for new research.

102 Genes Found Linked to Depression

What if we could find a way to ask about genes and the environment at the same time? Generation Scotland has invested heavily in this quest. The information content of our genetic material, DNA, is written into a very long string of just four letters, A, C, G and T. It turns out that when we look carefully, when a C is followed by a G, the C letter is sometimes chemically modified. These DNA marks are now easy to spot. It doesn’t change the genetic information as such, but it can change whether a nearby gene is switched on or off. To stay healthy we need the right genes switched on in the right tissues and the right time from birth onwards.

We call these DNA methylation marks, or DNAm. They can be affected by the environment, our lifestyle and our habits. A very good example is smoking. We ask you about your smoking history – ‘never’, ‘past’ or ‘present’.

With this information to hand, we (and others) have shown a very strong association between specific DNAm marks and smoking history. In fact, the signatures are more telling than the answers you give to the question on smoking history!

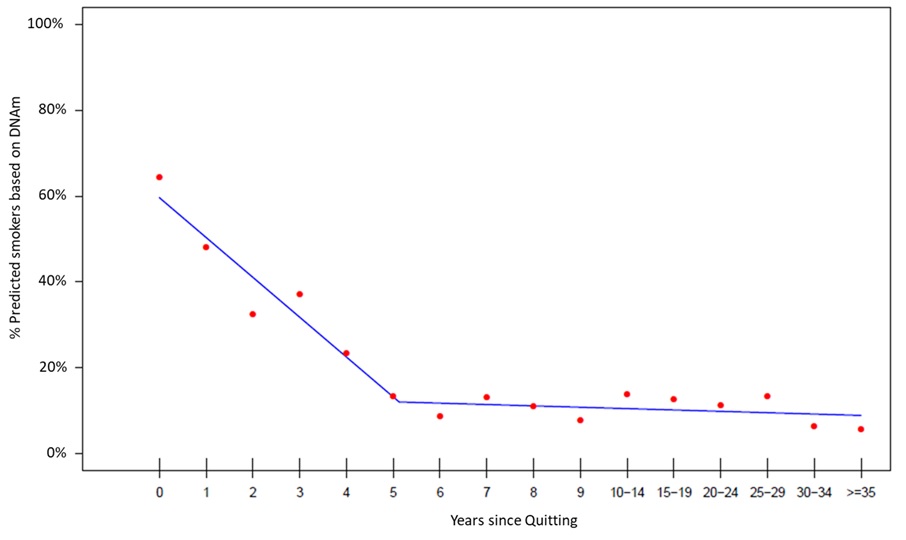

Epigenetic signatures of starting and stopping smoking

Rate of predicted smokers compared to years since participants stopped smoking.

The figure shows what happens to the DNAm smoking signature over time. The good news is that some of the smoker-defining marks are lost more or less immediately after stopping. The less good news is that some linger on. Are those that linger pointing to genetic factors that play a role in the long term effects of smoking? That is just one question we now want to test.

In other studies, we have found DNAm signatures that are associated with depression and dementia. These signatures add greater weight to genetic or lifestyle factors alone. It goes further than that. Some of us age faster, others slower than the rest. A whole host of factors contribute – how we have been brought up, how we live our lives, our occupation, where we live, our economic circumstances, general health and well-being. Remarkably, the tick-tock of time can also be seen in these DNAm signatures. This biological ‘clock’ serves as a consistent measure from which to deduce which aspects of our lives could be best changed for the better. We will keep you posted as we learn more.

Recent comments