‘Sometimes it’s hard to be a woman, giving all your love to just one man.

You’ll have bad times and he’ll have good times, doin’ things that you don’t understand

But if you love him you’ll forgive him, even though he’s hard to understand

And if you love him oh be proud of him, ’cause after all he’s just a man

Stand by your man’ (Billy Sherrill & Tammy Wynette, 1969).

The previous blog focused on Sarah Baird’s early life in Dundee, before she left with her young husband, George Robertson Nicoll, on the Royal Saxon in 1848. It’s now time to turn to her life in Australia, acknowledging that neither George’s book (Fifty Years’ Travels etc.) nor his journal (The Life and Adventures of Mr. George Robertson Nicoll) say very much about her life. Children were born and died, gold was discovered and stolen, houses were built and sold, businesses were established and passed on, ships were purchased and wrecked, and through all of this, George was constantly on the move, either travelling within Australia or journeying to and from America, Dundee, the Far East and eventually around the world twice. Sarah, meanwhile, was (we can only imagine) the loyal wife, mother and home-maker, living as a single parent for sometimes years on end, and at other times, travelling with George, putting up with the privations and hardships that went along with being a settler in New South Wales in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Because George makes so little mention of Sarah, I have had to follow his story, thinking all the while – but what about Sarah? – locating this in wider literature and using my imagination to do the rest.

Emigrating to New South Wales (NSW), March-July 1848

Sarah’s emigration journey must have been exhiliarating, terrifying, and often gruelling. It is reasonable to assume that she may never have been at sea before, and yet here she was, responsible for not just her own life and well-being, but for that of 10 month-old George Wallace, whom she was still breastfeeding. The small family left Dundee on a steamer for Leith (Edinburgh’s port) in March 1848 and then travelled to London by another steamer (a three-week journey) where they waited for a week at an emigration depot while the barque, the Royal Saxon, was made ready for sail.

Conditions on the Royal Saxon were, initially, good – there was plenty of fresh food and water, and the passengers settled down and organised themselves for the three-month passage. Over the course of the journey, however, everything changed. First, they hit storms in the Bay of Biscay, and everyone was seasick. George tells us that he could ‘hear the heavy seas coming on board the upper decks, thumping like great guns, which made the women and children scream, thinking they were going to the bottom’ (Fifty Years Travels, page 2). They then passed Gibraltar and onto the Tropics where they were becalmed for two weeks. The drinking water was, by this time, stinking and rotten, and passengers and crew alike became ill with fever. A young Scottish man from Glasgow in Sarah and George’s berth died and was buried at sea, his body sewn in canvas with a lump of stone, and ‘slid over a hatch into the deep’ (journal, page 36). Meanwhile, baby George Wallace became ‘very ill indeed’, ‘reduced to a skeleton, having got the Ricketts’ (op. cit.) The ship’s doctor advised Sarah to wean him, which, George notes ‘was very bad at this time’ (op.cit.). How George Wallace must have cried and cried! The doctor himself died soon after, and was also buried at sea.

From here on, the voyage seems to have been unremarkable. George tells us that they fell in with the trade winds, which made it cooler and everyone’s health improved, and the journey progressed satisfactorily. He made himself useful repairing blocks for the ship’s captain, while Sarah looked after her own and other families in their berth. Eight babies were born on the voyage, one to Sofie McDonald (aged 23) from Ross-shire, who gave birth to a son. It seems very likely that Sarah would have been involved in the birth in some way, either supporting Sofie’s labour or looking after her other children, John (aged 4) and Murdoch (aged 2). Three children died on the journey (no names are given); the mortality rate for seaboard infants was extremely high, with as many as one-quarter of infants not surviving the voyage.[1] Margaret Hinshelwood, who travelled to Queensland as a Scottish emigrant in 1883, gives some clues about what it felt like to be a woman passenger:

‘What a strange world we live in, one weeping and another rejoicing. Last night the sound of mirth and music ranged from forecastle to stern, and before dawn the wail of sorrow echoed over the peaceful sea. A fine little fellow of eighteen months was seized with croup and severe bronchitis in the night, and though the doctor tried every remedy, it was of no avail. The poor mother was nearly frantic, it came so suddenly, so unexpected. I could not go on deck to see the little body consigned to the waves. I felt it would be more than I could stand. The captain desired as much quietness as possible, as there is so much illness on board.’[2]

Life in NSW, 1848-1858

Arriving in Sydney must have been a welcome relief for everyone – the sun, the sky, the birds, the light, the dry land! Then again, the mosquitoes, the flies, the snakes, the spiders… And yet this was Sydney in winter, and the Southern hemisphere was experiencing a period of unusually cold and wet weather (Ashcroft et al., 2014; Neukom et al., 2014). Maybe this felt a bit like home? Sydney, like Dundee, was a place of great contrasts, with a lot of poverty, unmade streets and hastily thrown up buildings, but at the same time, a substantial number of public and private buildings, churches, libraries, theatres, banks and shops, a court and a police station. With a population of around 50,000 people, it was considerably smaller than Dundee (reckoned at about 80,000 in the 1851 census). But it was a city that was growing all the time, and one that was about to benefit – as Melbourne did – from the profits from gold.

This was a busy time for George: he travelled a lot and spent considerable amounts of time away from home, chasing gold in California, NSW and Victoria, and farming at Shoalhaven. It was also a busy time for Sarah, who had four more pregnancies that we know about and four more children (there may have been other pregnancies that did not go to full-term). It seems that every time George returned home, Sarah got pregnant again. Was she happy? We cannot know, but there is at least one suggestion in George’s journal that she may have felt lonely; why else would she have walked miles each day to bring him his lunch (journal, page 41). Of course, Sarah would have made friends – she would have had to, just to survive. But the family’s constant moves must have made it difficult to sustain mutually supportive relationships, and while Sarah would have received occasional letters from home, these would have taken months to arrive. [3]

Five months after they arrived in Sydney, George headed off for the Californian gold rush, leaving infant George Wallace and Sarah, now 4-months pregnant, living in a two-roomed house at Miller’s Point in Sydney; Mary was born in May 1849. When he returned in 1850, George was penniless. Not only had he been unable to get anywhere near the goldfields because of snow, he had been shipwrecked on the way back. How did Sarah manage when he was away? And how did they all manage when he came back? Over the next two years, George spent many months away from home, firstly, digging for gold at Maitland Point in NSW, and then at Mount Alexander in Victoria. Another child was born in October 1851 – Bruce Baird – and in March 1852, the family relocated to Melbourne, where George rented a small cottage in William Street, before heading off with the family for the goldfields, along with ‘two mates’ (sailors William Trail from Dundee and Jamie Lawton from Lerwick). He writes in his journal:

‘The wife and children rode on the dray while we [the men] walked. This was the only way we could get up as the road was very rough and the weather hot with plenty of mosquitoes, flies and hot winds, worse than Sydney. We arrived there in about six days, camping at night underneath a tarpaulin. We enjoyed it much as we were young and strong…’ (page 94).

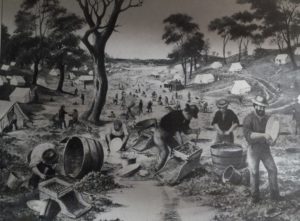

This does not sound like much fun to me, with three children under five years of age! At Golden Gully, George and his two mates built a wooden-framed house covered in tarpaulin, divided into two rooms (one for the men and one for the family). The men worked together for a time digging for gold, while Sarah kept house.

Life in the gold fields cannot have been easy for Sarah. Not only were there few women, but those who were there were as likely to be sex workers as they were wives and mothers.[4] George tells us that the children became unwell because of the heat and the ‘bad water’, and George was left working alone, after his two mates took off for Bendigo and Ballarat following new discoveries there. One of the only stories that George tells us of this time is of Sarah’s care for two neighbours on Golden Gully. The men were very sick, and Sarah fed them, cleaned them and looked after them for a week until they were well again; they gave her 2 ½ ounces of gold in thanks. George’s digging was ultimately successful: over time, he amassed 17lbs of gold (a considerable amount, then and now), and with this carefully stashed and a loaded gun by his side, the family headed back to Sydney, where he bought and renovated an old property, the Saracen’s Head Hotel, then a shop and dwelling-houses ‘which proved a good investment’ (journal page 99). George returned to the goldfields, working with limited success, until Sarah wrote to tell him to come home again; we do not know why. He stayed only for a short time and returned to the diggings again, ‘just making wages or thereabouts’ (journal page 103), before returning to Sydney where he bought the goodwill, stock and a general store in Burwood, Sydney. From here, he supplied goods to the team of navvies working on the construction of the Sydney to Parramatta railway. He also got up early each morning to go into the bush and fell ironbark trees, selling firewood around the houses in Sydney. After building up the business, he sold it for a profit, and having heard there was money to be made in farming, he decided to try his luck in Shoalhaven. He subsequently bought a farm with crops and cattle at Shoalhaven, where land was said to be fertile and plentiful, and took his family to live there, including another baby boy, Allen George, born in November 1854.

Time passed, and George tried and failed to make a success of farming. Sarah was pregnant again, and George tells us in his journal that she was unwell, so he bought 2.5 acres of land, along with a clearing lease, and built a cottage at Nowra on higher ground, because the doctor said that ‘the low ground was killing her’ (page 105).

Soon after, another baby (James) was born in May. Meanwhile, George sustained heavy losses at farming and Sarah was still unwell, so the family went back to Sydney, again renting a house on high ground. When the doctor recommended a return to Scotland, I can only guess that Sarah must have been overjoyed.

But what was wrong with Sarah? Was this a physical illness – perhaps a respiratory problem (such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD) brought on by her 10 years’ working in a linen factory, and made worse by the damp flood-plains of Shoalhaven?[5] Or was this a mental health problem – was Sarah suffering from postnatal depression, or was she simply missing her family back in Scotland? Powell (2007) outlines many of the challenges faced by women in this new world:

‘The trauma of being a new immigrant and the loneliness and separation that it entailed could prove to be defeating for both men and women. […] But women more likely to die from other causes – high numbers of women died from respiratory diseases such as bronchitis and pneumonia. Moreover, women of childbearing age throughout the country had to contend with the complications of pregnancy and childbirth which often proved fatal’ (page 76-77).[6]

Return migration, 1858-1862

After 10 years in NSW, the family (Sarah, George and their five children) returned to Dundee in 1858. George paid for second-class berths on the clipper Duncan Dunbar, sailing on 10th February 1858, a ‘splendid passenger ship’ with ‘mostly squatters and wealthy colonists’ (as George’s journal relates, page 107).

After a 90-day passage, they travelled by steamer to Dundee, arriving in the middle of May 1858, with a white cockatoo, two Gilear parrots and two dozen Java sparrows. They returned, to all appearances, as successful colonists, coming ‘home’ to Dundee to educate their three older children, no doubt bearing gifts for their many nephews and nieces, and something special for Sarah’s mother, now 69 years of age (Sarah’s father had died the previous year in 1857). The family moved into a rented house in Lochee, with a large fruit and vegetable garden, and spent the summer visiting friends and enjoying the climate and scenery of ‘Bonne Scotland’ (journal page 108.) Six weeks later, the lure of gold meant that George was off again on another ship to Sydney. He was then away for the best part of three years, digging for gold at the Snowy River goldfields, and later working as a carpenter near Bathurst. During this time, Sarah’s lifestyle and happiness took a dramatic turn for the worse.

I was shocked to find her listed in the 1861 census records, living in a tenement flat in Albert Street, Dundee, with only her three eldest children; the two youngest had died, James, on 24th January 1859 (aged 1 year 8 months) of ‘scarlatina dropsy’ (scarlet fever), and Allan George, three months later, on 4th April 1859 (aged 4 years and 5 months) of ‘effusion on the brain’ (possibly meningitis), which George calls ‘hooping cough’. Both deaths were registered by George’s brother, Thomas; George is recorded on the death certificates as a ‘farmer from Nowra, Shoalhaven, Australia’. This was not actually accurate, but may have been felt to be more appealing than ‘itinerant gold digger’! George does not mention the children’s deaths in his book, but he does in his journal, where he describes arranging for a headstone to commemorate them when he returned to Dundee in July 1861, with the intention of ‘settling for good in Scotland’ (as he says in his book, page 68).

How did Sarah cope with all of this loss and grief on her own? Of course, infant mortality was a massive problem in early Victorian Scotland. For example, in 1861, children under 10 years of age made up 54% of all deaths in Glasgow, and figures for the years 1861 to 1870 show that tuberculosis, whooping cough, and diarrhoea and dysentery accounted for the highest number of child deaths. (Flynn et al., 1977: 404-5). But knowing that it is a common occurrence cannot in any way take away from the terrible loss this must have been to Sarah and to the other children.

And how did the little family readjust to George’s presence again in 1861? It must have been strange for everyone. He had been away for three years, and it seems likely that George Wallace (at 14 years of age) would have, by then, seen himself as the ‘man of the house’. The other children were 12 and 10 years, and were used to having Sarah to themselves. And how did Sarah feel? She was pregnant again within a month of George’s return. I would like to think that she still loved George and that this was a union of equals. In truth, George had conjugal rights[7] and this pregnancy may not have been something she wanted. Whatever the truth, George could not settle back in Dundee. He hated the Scottish winter and suffered from ‘rheumatics, headaches and toothaches’ (Fifty Years’ Travels etc., page 69). He longed for the warmer climate, and persuaded Sarah to go back to Sydney with him again. I can only guess that she was glad to go too, sickened by the deaths of her two youngest children. The family returned to NSW, again travelling as assisted migrants in March 1862, this time on the Hotspur. Baby John Baird was born on the journey, and it was Sarah who appeared in the statistics of births on board.

Settling in NSW, 1862-1897

The next thirty years or so seems (on the surface) to have been a more settled time for the family. George set up a new business in Sydney, working as a produce agent, first representing the South Coast, and later trading on the North Coast on the Richmond and Manning Rivers, and he brought his two elder sons into the business. George named one of his steamers the Sarah Nicoll and another the Lass o’ Gowrie, built for him in Dundee. Another child was born in Paddington, Sydney, in October 1867. Named David, he was a much-cherished last child; his siblings were 20, 18, 16 and 5 years of age. George was, by this time, relatively wealthy. Son George Wallace married in 1872 as did Bruce Baird the following year, and both went on to have children of their own soon after. George says very little about this period in either his book or his journal, so it is difficult to be sure what either he or Sarah was doing. An obituary states that Sarah was ‘of a lively and intellectual disposition, and was possessed of considerable literary ability, and her kindly efforts in the cause of charity were many’ (The Australian Star (Sydney) Monday 9 August 1897 p.7). This suggests that Sarah – never afraid of hard work – was probably a volunteer for some voluntary organisation or church society, and she may even have written about her own adventures (though presumably without using her own name[8]). So far, I have not been able to find any evidence either of Sarah’s writing or her charitable work.

Inevitably, there were highs and lows over this time. The two elder sons did well in the shipping business, building it up considerably, and between them, had a combined fleet of 44 steamers. They have been described as ‘iconic figures in the Northern Rivers region’, who had ‘opened up the area to trade’.[9] They also became politicians, at both local and state level: George Wallace was an alderman and later Mayor of Canterbury in Sydney, and Bruce Baird represented the Richmond electorate in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly (Jehan, 2007). Behind the story of the family’s success, there were, nonetheless, other, more difficult life-events. In 1870, their only daughter Mary ran off with a married man, whom she married bigamously, each using false names. Mary came back home the following year, presumably in disgrace, and her father initiated a private prosecution against her former partner. Mary did not then marry until 1882, and this was to a middle-aged widower friend of her father and brother. Just as shocking for the family, son George Wallace’s wife, Helen, had an affair in 1882, while George Wallace was in Dundee commissioning the building of a steamship; two of her babies had died earlier that year, and it seems that she was struggling on her own. George Wallace subsequently divorced her, taking custody of their three remaining children. The divorce caused a public scandal (as all divorces did)[10], and was carried in all the local newspapers for days on end; extremely distressing for Sarah, who may have felt either/or/ both sympathy and fury with Helen, whose experience of motherhood was not unlike her own.

George Wallace married again in 1883, and went on to have six more sons. Soon after this marriage, Sarah and George’s last child, David, a painter, died of ‘phthisis’ (tuberculosis) after ten months of illness, at 18 years of age on 12th October 1885. George and Sarah were distraught, as demonstrated by the eulogies in the press and also the huge obelisk that was erected in the Rookwood cemetery in Sydney (Blog 3 discusses the impact of loss and bereavement on this family).

Soon after David died, George and Sarah went back to Scotland in 1886 to visit family and friends. They travelled in relative comfort on the New Zealand steamship, the Tongariro, and if George is to be believed, they both enjoyed the trip, following it with a three-month holiday in Tasmania. George went on to spend the next ten years travelling around the world twice, while Sarah lived with her son Bruce and his family. She died there on 6th August 1897, not long after celebrating her 74th birthday; George was not with her.

Conclusion

This blog began, tongue in check, with the first verse of the song, Stand by your Man. Looking at Sarah’s life as a whole, it is clear that this is what she did: she stuck by George ‘for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health’, as traditional marriage vows dictate. But did she? She did not accompany him on his last two world trips and was not living with him at the time that she died. In the end, I suspect that she stood by her children and her family, not her man. And maybe that was the best – and the only thing – that she could do, as a woman of her time.

Viviene E. Cree

25th November 2019

Primary Sources

Nicoll, George Robertson (1890). The Life and Adventures of Mr George Robertson Nicoll, unpublished journal.

Nicoll, George Robertson (1899.) Fifty Years’ Travels in Australia, China, Japan, America Etc. London: self-published.

References

Ashcroft, Linden; Gergis, Joëlle & Karoly, David, John (2014). A historical climate dataset for southeastern Australia, 1788-1859, Geoscience Data Journal 1(2): 158-178. doi: 10.1002/gd3.19

Cooms, Roger (2014). Shoalhaven District. Pictorial History. Alexandria: Kingsclear Books.

Frost, Lucy (1995). Immigrant women in narratives of divorce. In Richards, Eric (ed.) Visible Women. Female immigrants in Colonial Australia, Visible Immigrants: Four. Canberra: Centre for Immigration and Multicultural Studies, National University: 85-111.

Jehan, Jean (2007). The Nicoll Brothers. Pioneers of Northern Rivers Shipping, Hurstville: Hurstville Family History Society Inc.

Lai, Peggy S. and. Christiani, David C. (2013). Long term respiratory health effects in textile workers. Curr Opin Pulm Med. Mar; 19(2): 152–157. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32835cee9a/ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3725301/ Accessed 15th October 2019.

MacDonald, Charlotte (ed.) (2006) Women Writing Home 1700-1920: Female Correspondence Across the British Empire, Volume 5: New Zealand, London: Pickering and Chatto.

Neukom, Raphael; Gergis, Joëlle; Karoly, David J.; Wanner, Heinz; Curran, Mark; Elbert, Julie; González-Rouco, Fidel; Linsley, Braddock K.; Moy, Andrew D.; Mundo, Ignacio; Raible, Christoph C.; Steig, Eric J.; van Ommen, Tas; Vance, Tessa; Villalba, Ricardo; Zinke, Jens & Frank, David (2014). Inter-hemispheric temperature variability over the past millennium, Nature Climate Change 4: 362–36, doi: 10.1038/nclimate2174.

Powell, Debra (2007). ‘It Was Hard to Die Frae Hame’: Death, Grief and Mourning among Scottish Migrants To New Zealand, 1840 -1890, Unpublished Master of Arts in History dissertation, Waikato: University of Waikato.

Shlomowitz, Ralph and McDonald, John (1991) Babies at risk on immigrant voyages to Australia in the 19th Century. Economic History Review 44(1): 86-101.

Weber, Brooke (2018) ‘A Mad Proceeding’: mid-nineteenth century female emigration to Australia, Unpublished PhD thesis, London; Royal Holloway, University of London. https://2018weberphd.pdf.pdf

Endnotes

[1] Schlomowitz and McDonald (1991) state that although the seaboard adult death rate had declined to roughly the same level as the poorer classes of land-based people from Great Britain and Ireland, the child death rates remained significantly higher. Nearly one-quarter of infants died on voyages between 1838 and 1853. See also Powell (2007).

[2] Extract 1.5 Margaret Hinshelwood, account of voyage to Queensland, 1883 (NLS, Acc. 12149). In Breitenbach 2013: 293.

[3] Letter-writing was hugely important means of women keeping in touch, in spite of the great time-gaps. See MacDonald (2006).

[4] See permanent exhibition, Melbourne: Foundations of a City, Old Treasury Building, Melbourne.

[5] Textile dust related obstructive lung disease has been found to have characteristics of both asthma and COPD. See Lai and Christiani (2013).

[6] See also Weber (2018) on migrant women’s mental health.

[7] The assumption that ‘marital services’ (i.e. sexual intercourse) should be expected was not abolished in the UK until 1971.

[8] A delightful book written by ‘A Lady in Australia’, entitled Memories of the Past (1873), recounts the experiences of one middle-class woman who travelled to Australia in the early 1840’s with her husband on a convict ship from Gravesend, England.

[9] Website accessed 17 April 2019:

https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/Hansard/pages/HansardReult.aspx#docid/HANSARD-1820781676-75242

[10] Public scandal was one of the ways that the behaviour of women and men was policed. See Frost (1995).