Welcome to the 11th blog post in my series on my forebear, George Robertson Nicoll, who travelled as an assisted migrant from Dundee to Sydney in 1848 with his wife Sarah and infant son, George Wallace Nicoll. This blog post, like the others, draws from the journal and book written by George Robertson Nicoll, and published in 1890 and 1899 respectively.

As we will see, there was a connection with ships and the sea throughout George’s life. His story was a unique one, with all the ups and downs that are a part of every individual life. And yet at the same time, his story demonstrates the much bigger stories that were unfolding at the time – stories about the place of Dundee in shipbuilding, and more widely, about the part that ships played in industrialisation, colonisation and the empire. British shipbuilding grew throughout the nineteenth and into the twentieth centuries; servicing the British colonies was a key part of this growth. At one time, British shipbuilding dominated the world; as late as the 1950’s, a quarter of all ships were built in Britain.[1] Today, only naval ships and island ferries are built in Scotland and there are no shipyards in Dundee. This is the ‘bigger picture’ into which George Robertson Nicoll’s story must be placed.

Early years

It is no exaggeration to say that George Robertson Nicoll grew up with ships. His grandfather, Thomas, was a mast, pump and blockmaker at Fishmarket, Dundee; his father James and uncle George followed Thomas into the blockmaking business, working at East Shore, Dundee. But what did a blockmaker do?

As the name suggests, a blockmaker made blocks; a block was a set of pulleys or sheaves mounted on a single frame. Every ship needed hundreds of blocks of many different shapes and sizes; one reference suggests that a single, large, sail-powered warship in the mid-nineteenth century required more than 1,400 blocks of various kinds.[2] The best way to explain this is with a photo of blocks and a sailing ship’s rigging.

In the nineteenth century, shipbuilding went through a number of revolutionary changes, each contributing to make ships faster, safer, and able to go longer distances. So wooden ships were gradually replaced by iron and steel, sail was overtaken by steam engines and propellers took the place of paddles. Nevertheless, steam ships continued to have sails as back-up at this time, because they could not depend on being able to refuel with coal when on a long journey.[3] So blocks were still needed, in ever-greater numbers.

Some blockmakers (like George Robertson Nicoll) were mast, pump, and blockmakers. They worked alongside a wide range of skilled craftsmen (they were all men) building and repairing ships. These included blacksmiths, carvers, coopers, glaziers, joiners, leadworkers, metalworkers, painters, riggers, ropemakers, sailmakers, shipwrights and sparmakers. As demand for ships increased, so machines were invented that took the place of work originally done by hand; for example, Marc Brunel, father of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, developed machines for blockmaking at Portsmouth docks.[4]

As a child, George was expected to go after school to help his father in his blockmaking shop at the docks:

[…] my school hours were from 9 to 1 and 2 till 4, after which I had to go down to Father’s shop at the Docks, where I had to turn the grindstone, tread the turning lathe, help cut timber with the crossent [sic] often until 9 and even 10 at night, until I was that tired I was unable to walk home (Journal, page 14).

Poor George! Life wasn’t all work though. He had lots of opportunities to mess about in boats at the docks and on the river Tay. His aunts had both married seamen. Aunt Jean had married John Spink, who went on to become Commander of the Dundee & Perth Shipping Company’s SS Perth, a wooden paddle steamer that travelled between Dundee and London from 1834. This ship and its partner SS Dundee were ‘the most luxurious and fastest steamers on the east coast and their Masters took great pleasure in outpacing their Leith and Aberdeen rivals’.[5] George tells us that ‘when they made their first appearance on the River Tay, at Dundee, half the inhabitants turned out to see them’ (Journal, page 5).

Aunt Janet, for her part, had married George Wallace, also a shipmaster, from South Street, Perth. George Wallace was captain and owner of the schooner Margaret Simpson, trading between Perth and London and sometimes to the Baltics. George recounts that he also went several times with Captain Ross on voyages of discovery to the North Pole (Journal, page 22).[6]

On special occasions, George and his brother John would get up at 3am to travel on one of the paddle steamers, Tay or Lass o‘ Gowrie, to Perth for the day. They would visit Captain Wallace and aunt Janet, who, by this time, were running the Gowrie Inn at the Watergate, Perth. George named his first son ‘George Wallace’, in honour of this, his favourite uncle.

In 1836, George (aged 12 years) was apprenticed to Thomas Adamson,[7] then the largest shipbuilder in Dundee. Although he doesn’t mention this, it seems likely that he may have worked on the building of the coastal paddle steamer the Forfarshire, which was completed in 1836. The ship ran aground two years later on 7th September off the Farne Islands on its regular run north from Hull to Dundee. Grace Darling and her lighthouse keeper father attempted the rescue and this became the story of legends:

One of the ships that George does name is the brig Cairo, launched in 1839 from the Calman yard.[8] George had helped to rig her out, and when she was ready for sea, he approached the captain to ask if he could sail with her. Captain Thomas agreed, but George’s father refused to let him go. George remembers that ‘the captain and he had a great row about it, and I had a good cry about it and felt awfully discouraged and disappointed’ (Journal, page 19). Soon after, he ran away to sea, taking a smack to London, where he met up with his cousin David Spink, then working on an Aberdeen ship at St Katherine Dock. The captain contracted to take him on as a sailor (he had these useful extra skills, after all!) and George looked forward to the voyage to Cape of Good Hope. Unfortunately, he had a bad accident and couldn’t go – he fell down the ship’s hold one evening and injured his knee. He was forced to return home in disgrace and penniless, where he got ‘plenty of scolding and little sympathy’ (Journal, page 21). When he was well enough, he returned to work as a blockmaker for his father, firstly in Dundee, and later in Perth, until the early 1840’s recession hit and five of Perth’s seven shipyards closed down (Journal, page 22). George had to return to Dundee, out of work.

Middle years

Times were hard in the 1840’s for those in the shipbuilding industry.[9] A large number of firms (including Thomas Adamson) went out of business completely. When George came back from Perth, he wasn’t employed in blockmaking, but as a storeman and traveller for his brothers, James and Thomas, as they traded under the name of the ‘Dundee Iron Company’. But this was not to last. The brothers’ business struggled and by 1847, he was unemployed again.

Once in New South Wales, George established a mast, pump, block and spar making business at the docks in Sussex Street, Sydney.[10] Some years later, good use of his blockmaking skills at in building wooden, ‘weatherboard’ cottages and repairing fences on a sheep-station. He was a resourceful man, able to turn his hand to many different practical tasks. He was also an entrepreneur, able to spot a gap in the market and capitalise on it. It was this that led him (by then, 40 years of age) to begin a produce agency business in the early 1860’s, with the support of a financial partner, Thomas Isbester.[11] The agency was based at Lime Wharf, Sydney. Over the next 20 years, he built a successful business into which he brought his two sons, George Wallace Nicoll and Bruce Baird Nicoll,[12] taking produce and passengers to and from the developing communities north and south of Sydney. George’s sons went on to expand the business greatly, initially working together as G & B Nicoll (also known as Nicoll Brothers), and then separating in the mid-1880’s to set up their own businesses based on trade in different rivers.[13] The Nicoll sons went on to become extremely wealthy, influential men, so described in the various books that have been written about them and their contemporaries.[14] George and wife Sarah’s only daughter, Mary, meanwhile, married her father’s business partner, William Wigmore, in 1882; William also successfully traded on the Richmond River for many years, and is still celebrated today in names of streets and buildings in Ballina.

George’s first venture, in 1864, was to buy a schooner called the Spec for trading on the South Coast, Wollongong, Kiama and Shoalhaven. Things went well for a time, and trade increased, then on 17th October 1865, the Spec sank in a storm off Kiama. Three men were drowned and one managed to swim ashore to safety. The ship was uninsured; George began a collection for the dependents of the men and raised £100 (Journal, page 113). Following the accident, Isbester withdrew from the produce agency. George’s next venture, in 1866, was to have a schooner built at Broken Bay, on the north coast. The Sarah Nicoll was ready in eight months and George traded her to the Richmond River, where he took timber and maize from settlers, in return for produce (oil, bags, foodstuffs etc.). He also sent the vessel twice to New Zealand, before lengthening her into a three-masted schooner. The following year, he had a brigantine, the Saucy Jack, built on the Manning River, again for trading to the Richmond River.

In 1873, George bought a ketch, the Confidence, trading her to the Bellinger River and the Macleay. In 1877, he took his boldest step so far and had a steamer, named the Lass o’ Gowrie, built by engineer John Keys at the Abden Shipbuilding yard, in Kinghorn, Fife, for the Manning River trade.[15] When she arrived in New South Wales, the river mouth was found to be too shallow, so the ship was sold.

In 1883, George sold the Saucy Jack and, as he tells us in his journal, retired from the shipping business. This may not, however, have marked the end of his interest in shipping and shipbuilding. As the person who had established the so-called ‘Nicoll line’, it seems likely that although George retired from shipping, he continued to make money through investments in his sons’ and daughter’s businesses. He certainly continued to work from a warehouse and office, at 171 Kent Street, Sydney, at least until 1894.[16] He also built property after retirement, including ‘four new houses in the city, which occupied my time’.[17] (book, page 74).

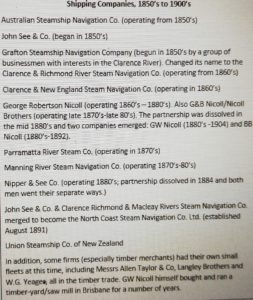

Looking back over this 20-year period, two features stand out. Firstly, it is evident that when George started trading on the south and northern coasts in the 1860’s, there were very few companies involved, but this changed considerably over time as new companies entered the field. By the time he retired from the business, there was significant competition for trade on the coastal rivers. A name-check of the shipping companies that were operating at this time includes:

The second noteworthy feature is the colossal number of ships that were lost at this time – wrecked in storms, stuck on sand bars and reefs and sunk following collisions with other ships. Few of the ships that the Nicoll family members built survived for more than a few years; today, the wrecks provide sanctuary for sea-life, as well as much-treasured dive-sites for scuba divers.[18]

The wider context

The story of the growth and eventual take-over of the Nicoll family’s shipping business mirrors the story of coastal shipping more generally. Initially, the expansion of shipping came hand-in-hand with the increasing numbers of white settlers; ships (ketches, schooners and brigantines) provided the only means of transport for goods and people at this time. Gradually, steamers replaced the sailing ships of the early years – as Richards (1977: 2) points out, steam navigation came to Australia as much as 23 years before the first railways. Shipping continued to be crucially important even after the railways began, because, as Richards outlines, the nature of the terrain made road and rail-building difficult:

The development of these shipping companies rested solely on the fact that, in the last century, sea communications were the only link with the outside world. […] Roads from one town to the next were little more than a pair of wheel ruts winding painfully through the bush, fording creeks and streams, and ending up at river jetties or mountain ranges. Horses were the only source of motive power, and coaches offered local services between towns not served by navigable rivers and large enough to warrant a service being run. Mostly, however, one travelled on horseback, or failing that, one walked. Cars (or horseless carriages) were unheard of in the bush for years after the first ones chuffed and spluttered their precarious and improbable way down George Street [in Sydney] (page 9).

Two shifts led to the eventual demise of the small companies, and with them, the shipping businesses of the Nicoll family. Firstly, as railways and roads became available, so easier and more comfortable (and significantly, less dangerous) forms of travel emerged. As a politician, Bruce Baird Nicoll campaigned for railways – he was, in a sense, an architect of his own demise. But he understood that this was the way the future was going. Secondly, as successful companies grew bigger, they were able to create considerable economies of scale, thus lowering the cost of freight for business and passengers alike. Small companies were unable to compete and were forced to sell out to the bigger companies.[19] The writing was on the wall for the Nicoll line of steamers almost from its inception. Richards (1977) is sorry to see the end of the fleet belonging to George’s son, George Wallace Nicoll:

He had lifted the standard of our coasters from small, often slow tramps to a new high; fast, pretty little packets that were the envy of all (page 36).

Later years

What George Robertson Nicoll did most in the last 10 years of his life was the thing he loved best – he travelled on ships. He went around the world twice, visiting new countries and cultures, and relishing the opportunity to try out different ships: iron screw barque steamers, single screw steamers and royal mail steam ships. He even travelled on the maiden voyage of the RMS Lucania on 2nd September 1893, travelling first-class. Built in Govan and owned by the Cunard Steamship Line Shipping Company, she was the fastest and largest liner afloat at this time, carrying 2,000 passengers from Liverpool to New York.

The last half of George’s book is taken up with his accounts of his travels. He describes in minute detail the places he visited, the people he met, even the meals he ate. For the lover of tourism history, this is a goldmine! George’s story brings to mind a quote from Robert Louis Stevenson, who himself travelled on a Nicoll steamer (the Janet Nicoll) from Sydney to Auckland in 1890:

For my part, I travel not to go anywhere but to go. I travel for travel’s sake. The great affair is to move; to feel the needs and hitches of our life more clearly; to come down off this feather-bed of civilization, and find the globe granite underfoot and strewn with cutting flints. […] when the present is so exacting, who can annoy himself about the future? [20]

Viviene E. Cree

February 2020

Primary Sources

Nicoll, George Robertson (1890). The Life and Adventures of Mr George Robertson Nicoll, unpublished journal.

Nicoll, George Robertson (1899.) Fifty Years’ Travels in Australia, China, Japan, America Etc. London: self-published.

References

Bruce, George J. with contributor Ian Garrard (2013). The Business of Shipbuilding. London: Informa Law, Routledge.

Daley, Louise Tiffany (1966). Men and a River. Richmond River District 1828-1895. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Horsburgh, D. (nd). James Horsburgh (1786-1860) Shipbuilder in Dundee, http://www.fdca.org.uk/ Accessed 12/02/2020.

Jehan, Jean (2007). The Nicoll Brothers. Pioneers of Northern Rivers Shipping. Hurstville: Hurstville Family History Society Incorporated.

Lythe, S. G. E. (1964a). Shipbuilding at Dundee down to 1914. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 11(3): 219-232.

Lythe, S.G.E. (1964b). Gourlays. The Rise and Fall of a Scottish Shipbuilding Firm. Dundee: Abertay Historical Society No. 10.

Moss, Michael S, and Hume, John R. (1977). Workshop of the British Empire: Engineering and Shipbuilding in the West of Scotland. London: Heinemann Educational Publishers.

Myers, Francis (1886). The Coastal Scenery of New South Wales. Harbours, Mountains and Rivers. Sydney: Thomas Richards, Government Printer.

Richards, Mike (1977). North Coast Run. Men and Ships of the NSW North Coast. Killara, NSW: Turton & Armstrong.

Stevenson, Robert Louis (1897. 1993). Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes and Selected Travel Writings. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wood, James (1998). Shipbuilding. Scotland’s Past in Action. Edinburgh: NMS Publishing.

Further reading

Craig, Robin (1980). The Ship. Steam Tramps and Cargo Liners, 1850-1950. London: National Maritime Museum.

Harcourt, Freda (2006). Flagships of Imperialism. The P&O Line and the Politics of Empire from its Origins to 1867. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Lythe, S.G.E. (1962). The Dundee Whale Fishery. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 9(2): 158-169.

Mackenzie, John M. and Devine, T. M. (2011). Scotland and the British Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ogilvy, Graham (1999). Dundee. A Voyage of Discovery. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing.

Walker, Fred M. (2010). Ships and Shipbuilders. Pioneers of Design and Construction. Seaforth Publishing.

Endnotes

[1] See Moss and Hume (1977). Also https://www.savetheroyalnavy.org/can-british-shipbuilding-be-revived/

[2] The Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol III, (1847) London, Charles Knight, p.436.

[3] https://www.rmg.co.uk/discover/explore/shipbuilding-1800%E2%80%

[4] See Bruce (2013). Also https://www.flotilla-australia.com/nicoll.htm

[5] See https://dpandl.co.uk/history/ Accessed 10/2/2020.

[6] George tells us that his uncle had great stories to tell of his travels with Captain Ross, who in 1818, received the command of an Arctic expedition, the first of a new series of attempts to solve the question of a Northwest Passage. Second expedition 1829-1832. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Ross, Sir John”. Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

[7] Thomas Adamson shipbuilder came from Grangemouth and set up at the Seagate in Dundee in 1829. He later had a number of yards, including one at Broughty Ferry. Lythe states that Adamson was ‘early into steam – Dundee, Perth & London Company already owned a small steam tug- Sir William Wallace -built in 1829 by Adamson with engines by the Dundee Foundry’ (Lythe, 1964a, page 221). In 1842, Thomas Adamson was in bankruptcy and two unfinished vessels in his yard were sold by his creditors (Lythe, 1964a, page 222, citing Dundee Harbour Trust, Committee of Finance Minutes, 9 May 1844).

[8] See Friends of Dundee City Archives, 19th Century Dundee Ships (from the Directories) 1818-1898, http://www.fdca.org.uk/pdf%20files/19cShipsReg%20C.pdf accessed 10th February 2020.

[9] See Lythe (1964a).

[10] Obituary of George Robertson Nicoll in the Sydney Morning Herald, 20th May 1901, page 6.

[11] The partnership did not last. Two years later, it was dissolved, and George took over sole ownership of the company.

[12] Obituary of Bruce Baird Nicoll in the Northern Star, 24th September 1904, page 5.

[13] It is difficult to be sure the extent to which this was an acrimonious separation; similarly, it is unclear how far the two brothers were business rivals over the years. Of the two, it was George Wallace Nicoll who kept going for longer, not retiring until 1904, when he sold out to the North Coast Steam Navigation Company. Daley (1966: 129) suggests that he was forced to sell out. Bruce Baird Nicoll, meanwhile, had retired from shipping in 1892 to concentrate on politics.

[14] See Daley, 1966; Jehan, 2007; Richards, 1977. Also https://www.flotilla-australia.com/nicoll.htm (with pictures of some of the Nicoll ships).

In an interview in the Northern Star, Saturday 21st August 1897, page 2, George Wallace Nicoll (GWN) lists the many ships that he and his brother, Bruce Baird Nicoll (BBN), built and traded. There were also many other ships, as outlined by Jehan (2007).

The brothers began with the small schooner, Wallaby (1871), then built the Wallace, the Bruce and the Rob Roy schooners (1873), before going into steamers in 1877, when they imported the Bonnie Dundee, built by Gourlay Brothers of Dundee (see Lythe (1964b). They then bought the Truganini from the Tasmanian Government. In 1877, they imported the first Richmond and the Lass o’ Gowrie (with their father) from Dundee, followed in 1878, by the Australian. Then the Lismore was ordered and came out in 1880, as did the Fijian; two years later, sister vessels, the Casino and Helen Nicoll were imported from Dundee (GWN sold this on arrival), as was the Mallard, built for BBN. In 1883, a steamer called the Rook, re-named the Palmerston, was bought and subsequently sold. In 1884, the Janet Nicoll was brought out for BBN, as was the Bellinger for GWN, followed in 1886, by the Tweed No.1. In 1887, the Wryaallah was operating for BB Nicoll. The same year, GWN opened a shipbuilding yard at Terrigal, near Broken Bay, which built the Tweed No. 2, of wood, and the following year, the Byron. In 1892, BBN retired from shipping, meanwhile GWN relocated his shipyard to Jervis Bay, to ‘utilise that good, but much maligned timber, spotted gum’. The Wollumbin was the first boat launched there, followed by the Chindera in 1894, and later, the Orara and Dorrigo (with engines imported from Gourlay Brothers.) GWN then commissioned another new steamer Excelsior, in 1897, from Gourlay Brothers in Dundee; in the period between 1881 and 1900, they were responsible for almost half the shipbuilding in Dundee (see Wood (1998: 26-27). (Interestingly, Gourlay Brothers are described in the newspaper article as ‘near relatives of Mr Nicoll’, but this has still to be proved.) In 1900, GWN commissioned another two ships from Scotland: the Cavanba (built by Bow, McLachlan & Co. on the Clyde), and the Noorebah (built by Scott of Kinghorn Ltd., Fife). GWN finally retired from shipping in 1904, selling his fleet and wharves to the North Coast Steam Navigation Co. Ltd. BBN’s obituary (endnote 11) states that the Nicoll Brothers spent over £250,000 in steamships, droghers, wharfs, and other essentials.

[15] Report of the Lass o’ Gowrie’s departure in the Dundee Courier, Monday 18th February 1878, page 4.

[16] George wrote to the Mayor of Sydney in 1894 complaining about the ‘goat nuisance’ outside the new properties he had built in Gloucester Street, Sydney (letter dated 26th June 1894).

[17] The new houses were in Gloucester Street, Sydney, later compulsorily purchased (after George’s death) as part of ‘the Rocks’ redevelopment to make way for approach roads to the new Sydney Harbour Bridge.

[18] The SS Bonnie Dundee is one such ship, wrecked in December 1878, following collision with the much larger SS Barrabool. See https://mail.michaelmcfadyenscuba.info/viewpage.php?page_id=146, accessed 14th February 2020.

[19] See Richards (1977) pages 34-6.

[20] From Robert Louis Stevenson’s Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes, which tells the story of his 12-day hike through the Cévennes mountains in south-central France in 1878.