‘In 1852, Australia became the talk of the world. It was the moment in our history when there was nothing but gold.’ So writes Robyn Annear, as she tells the story of her great-great-grandmother’s experience of life as the wife of a gold-digger in Victoria in the early 1850’s.

167 years later, I visited the Victorian goldfields, retracing the steps of my own ancestor, Dundonian George Robertson Nicoll, who took part in gold rushes in California, New South Wales (NSW) and Victoria over a period of 12 years, on and off, from 1849 to 1861. His story – of failure as well as success – is the story of many gold-diggers of this period. Just as importantly, the repercussions of the gold rushes on both the landscape and the culture of both countries are still being felt today.

It was on the 24th January 1848 that gold was first discovered in John Sutter’s mill-race on the Sacramento River in California. Reaction to this momentous event was initially slow, but as news spread, what has been called the California gold rush began. By the middle of 1848, San Francisco was half empty, with three-quarters of the men off to the mines, shops closed, newspapers suspended and ships in the harbour deserted by their crews (Holliday, 1981: 35). The consequences of the California gold rush were ‘vast and far-reaching’ (Rohrbough, 1997: 1), felt not only across America, but also across the world, including 10,000 miles away, in what was then the Australian colony of New South Wales (NSW), where George Robertson Nicoll was living with his wife Sarah and young son George Wallace Nicoll. In his book of his travels, George describes the impact of the California gold rush on Sydney in late 1848:

‘In Sydney, hundreds sold off their household furniture, and also their houses, for what they could get. Those who could not dispose of theirs, borrowed money on the security of the title-deeds, if they could raise as much as would pay for their passage. Property could be bought at this time for a mere song, so great was the excitement’ (1899: 5).

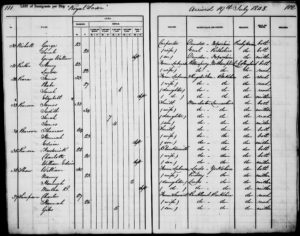

George tells us that there were no steamers fit to make the journey to California, so small coasting vessels were used instead, and he was kept busy making gun-cartridges and other fittings; the boats were being armed against pirates! George also made wooden tent poles and wooden portable houses to be shipped to San Francisco for people on the goldfields. By late December 1849, he himself ‘caught the gold-fever’ (1899: 6) and was persuaded to buy a share in the Sea Gull, a schooner that he had fitted out for the journey to San Francisco. The 25 shareholders hatched a plan, that half of them would go to the goldfields, while the rest would sail and trade on the Sacramento River. They would meet up in two years’ time and divide the profits or losses.

As things turned out, neither part of the plan succeeded. By the time they arrived (at the end of February 1850), the goldfields were swamped with diggers: most of the rivers and their tributaries had already been claimed and the gold-finds themselves were greatly reduced. Thousands of miners were giving up and heading for home (Holliday, 1981: 300). There was also, however, a more pressing problem, and that was the weather. Heavy snow meant that George and his mates were unable to even reach the goldfields, let alone dig for gold.

They were also unable to sell their carefully accumulated supply of fresh fruit, vegetables and provisions, because when they arrived, their boat was impounded by the Customs’ Authorities and all the produce confiscated.[1] George and his shipmates were forced to seek work where they could get it, some discharging ships in the harbour and others working on the roads. With his money rapidly dwindling, George signed up as an able-bodied seaman on a brig, the Lady Howden, bound for Sydney. Following shipwreck and various near disasters (including encounters with cannibals!), he finally returned to Sydney on a small man-of-war, the Bramble, in the middle of 1850. He had been away for eight months and had ‘saved nothing but what clothes I had on, viz shirt, trousers and hat’ (journal, page 82).

George’s experience was shared by many who clamoured to the California gold rush, then and later. Even when gold was discovered, the people who made most out of gold were not the diggers themselves, but the people who supplied them. Writing about the Scots who went to the Californian goldfields, Jenni Calder states that much of the gold acquired ‘was quickly spent. Wherever there were miners, there were those who supplied their needs – provisions, equipment and entertainment. Most of the supplies came via San Francisco, and none of them came cheap’ (2009: 106). This point is echoed by economic historians, Clay and Jones, who state that economic outcomes were ‘generally small or even zero for miners, but were positive and large for non-miners’ (2008: 997). George was lucky. When he got home, Sarah had saved enough to allow him to start work as a shipwright again, and he rebuilt his business, later supplying diggers with tents poles and pick-axes after gold was discovered in NSW. But the lure of gold was too strong, and by August 1851, he headed off in a party of 10 shipwrights, again determined to make his fortune.

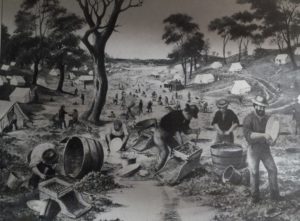

George’s second attempt at gold-digging was more successful than his first. His book of his travels details how ill-prepared they were for what lay ahead of them; for example, they took far too much equipment and lost a great deal of it on the way. The weather was cold and some members of the party soon lost heart and returned to Sydney. It was, as George describes, an uncertain and difficult life:

‘One moonlight night, about twelve o’clock, there was a rush of people tramping past our tent up the Turon [river], going to a new place just discovered. I rose, hastily got on my clothes, and followed them. They were going off to a place called Golden Point, about six miles farther up. I took a meal and my billy with me and went too, but did not get a claim. They were all taken, and the holders were waiting for the commissioner to come and give them the necessary documents before they could begin. Some of the men were lying on the ground, taking hold of the long grass with their hands, while others – rival claimants – hauled them off, swearing and fighting. I was too late for Golden Point, but fortunate enough to get a claim on the next point on the river – Maitland Point. I marked it out and left it in charge of one of my acquaintances while I returned for my mate and tent etc.’ (1899: 39).

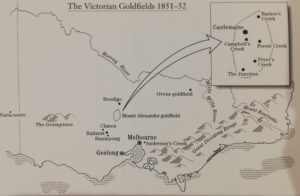

George spent four months at the digging, before returning to Sydney where another son, Bruce Baird Nicoll, had been born. This time he did the journey unencumbered by horses or equipment; he and his mate walked barefoot for five days (130 miles) carrying only a blanket each, later picking up a stagecoach at Parramatta. (There were no railways at this time.) George had earlier sent his gold pickings by government escort; this was a much safer (though expensive) way of taking gold back to Sydney. He then returned to the Turon, where he heard about gold being discovered at Mount Alexander,[2] 80 miles north of Melbourne. So he and his mate sold their claim and headed back to Sydney on foot again, before booking passages on a brig, the Thomas and Henry, bound for Melbourne.

After checking out that the goldfields seemed profitable, George went home to collect Sarah and the three children, and they all travelled together to Golden Gully at Mount Alexander, where George built a two-roomed tarpaulin house in a wooden frame, with one room for his family, and the other for his mates. It was now 1852.

George and his mates did find gold at Golden Gully; his share amounted to 17 pounds of gold, a substantial sum, then and now. The family returned to Sydney, where he bought a shop and dwelling houses, before the tug of gold caught him again, and he headed off for the Ovens diggings, travelling 400 miles on foot, and then another 300 miles in order to reach Mount Alexander again. George worked alone for a time, before teaming up with a man from Northern Ireland. In his book, he describes both the hard work and the risks attached to the digging process:

‘… we made a clearance and a start. We got out the washing stuff. The first tub washed out about two ounces. We went home rather cheery at our venture, and returned next day, commencing in the tunnels. In about three weeks’ work we got about three hundred pounds’ worth of gold out of it. We now all of a sudden got out of it, and tried another old tunnel. I was fossicating with my knife one day when I heard a cracking noise. I was lying at full length, with the candle lit, working in a crevice of the rock. The cracking continued, and I moved out as quickly as possible. All at once tons of earth and stones came crashing down, which buried pannikin, candle, knife and pick, and all but caught me. This was the last of these claims for me. They might be lucky, but they were also unlucky, and we thought it was time for us to clear out of it’ (1899: 53-54).

George returned to Sydney, following a letter from Sarah (another child was born), then went back again, this time to the Forest Creek goldfields at Mount Alexander, where he teamed up with another old friend and, going over old ground, they ‘did very well together’ (1899: 55) for a time. He then reverted to Sydney, where he bought a general store along with stock near Burwood, on the outskirts of the city. He did not return to the goldfields until 1859/1860, after a disastrous attempt at farming in Shoalhaven, which precipitated him taking Sarah and their five children back to Dundee. This time, he headed for the Snowy River goldfields in NSW, where he and his mates struggled for six weeks in heavy snow before he accepted a position at the Mitchell’s Creek quartz mine near Bathurst, working for the Glasgow company on wages, doing carpentry work and erecting engines and stampers. George subsequently had one final attempt at digging a claim for himself, but finding it unsuccessful, he sold it. In 1861, he worked his passage on the Oliver Cromwell, heading for London, to meet up with Sarah and the children again in Dundee.

So, what conclusions can be drawn from George’s experience of gold digging, and what evidence is there of the gold rush today?

Perhaps the most striking aspect of George’s account is how haphazard it all seems to have been. George was forever on the move, teaming up with different ‘mates’ at different times and in different locations, but always travelling. With little in the way of public transport, much of his journeying was done on foot. Life must have been hard, physically and emotionally, as diggers fought each other and the environment to gain rewards that were, for the most part, disappointing. Diggers had to pay the British government 30 shillings a month for the privilege of working a claim whether or not they found gold, and this meant that many lost what little they gained.

And yet on the more positive side, gold was the prize that encouraged George to test himself in new and often challenging situations. It also brought him into contact with people from all over the world – from across Europe and North America and from as far away as China. It also brought him face-to-face with the Aboriginal people whose lands and livelihoods were decimated by the destructive effects of gold on their land and livelihoods; this subject will be picked up again in Blog 10.

I have said that George was one of the lucky ones. It is estimated that 10% of diggers became very wealthy, 10% made enough to set up in small business or farm, the other 80% made nothing, or were worse off than if they had never left home. George was in the second group. His gold spoils allowed him to set up two businesses and, on another occasion, to buy a farm. None of this money lasted, however, and it was not until 1862 that George’s new career as a produce agent brought him the stability and prosperity that he was searching for.

Looking ahead, the kind of gold-digging that George and his mates engaged in (in both California and Australia) was soon overtaken by big companies and massive machinery that could dig much deeper and further than the itinerant diggers had ever achieved. And while the early diggers had felled thousands of trees (often for firewood, sometimes for building mine shafts and houses) and cleared vast areas of native bush, now large companies also polluted rivers and streams in the dash for profits from gold. The story of the devastation wrought by gold is still being played out today in South Africa, Nevada, Indonesia, Western Australia, Peru, the United States, Canada, Papa New Guinea, Japan and China.[3] Meanwhile, Mount Alexander today is a pleasant place to ramble; nature seems to have recovered from at least some of the damage done by the nineteenth century diggers.

Garden (2001) is less certain. He writes:

‘In the bush around gold towns […], vegetation grows on the uneven clumps of clay and stone which cover the landscape. It might be mistaken for harsh natural bushland, but in reality, these are disrupted and degraded ecosystems, devoid of any of the range of species of flora and fauna which once were present. Apart from possums, the small mammals are almost universally gone’ (page 35).

He concludes:

‘Ironically, the scenes of these environmental cataclysms have in recent years become valuable sites in our cultural heritage. […] Environmental issues and repercussions are generally not yet included in our study of or interest in gold mining, but their time must come if we are to learn to live more sensitively in this fragile world ’ (page 43).

This is a hugely important point to end on.

Viviene Cree

21st December 2019

Primary Sources

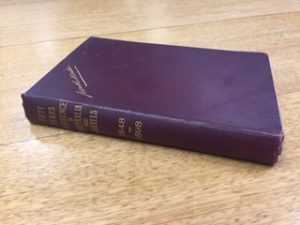

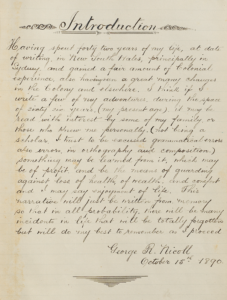

Nicoll, George Robertson (1890). The Life and Adventures of Mr George Robertson Nicoll, unpublished journal.

Nicoll, George Robertson (1899.) Fifty Years’ Travels in Australia, China, Japan, America Etc. London: self-published.

References

Annear, Robyn (1999). Nothing but Gold. Melbourne: The Text Publishing Company.

Calder, Jenni (2009). Frontier Scots. The Scots who Won the West. Edinburgh: Luath Press Limited.

Clay, Karen and Jones, Randall (2008). Migrating to Riches? Evidence from the California Gold Rush. The Journal of Economic History 68(4): 997-1027.

Garden, Don (2001). Catalyst or cataclysm? Gold mining and the environment. Victorian Historical Journal 72(1&2) Special Issue Celebrating 150 Years of Goldmining in Victoria: 28-44.

Holliday, J.S. (1981). The World Rushed In. The California Gold Rush Experience. New York: Touchstone.

Rohrburgh, Malcolm J. (1997). Days of Gold. The California Gold Rush and the American Nation. Berkeley, LA: University of California Press.

Further reading

Clarke, Percy (1889). Three Diggers. A Tale of the Australian Fifties. London: Faudel Phillips & Sons.

Flett, James (1970). The History of Gold Discovery in Victoria. Melbourne: The Hawthorn Press.

Hocking, Geoff (2007). Castlemaine. From Camp to City. A Pictorial History of Forest Creek & the Mount Alexander Goldfields 1835-1900, 2nd edition. Castlemaine: New Chum Press.

Korzelinski, Seweryn (1979). Memoirs of Gold-digging in Australia. Translated and edited by Stanley Robe. St. Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press.

Ritchie, John (1975). Australia: As Once We Were. Melbourne: Heinemann

Victorian Historical Journal 72(1&2), September 2001, Special Issue Celebrating 150 Years of Goldmining in Victoria.

[1] In his journal, George explains that British vessels were not allowed to trade on the American coast or on any of its rivers (1890: 50).

[2] Mount Alexander was the name originally given to all the goldfields around present-day Castlemaine, as far as Bendigo in the north (Annear, 1999).

[3] The world’s 10 most prolific goldfields are described in 2011 in an online article (see cmi-gold-siver.com/) I have added China to this list, because the gold-mining industry here is currently undergoing massive expansion (see www.gold.org/).