As a native Dundonian, I have spent my life telling others that Dundee is a “much maligned city”. The Dundee Council website seems to agree with me. It states:

‘Dundee, the City of Discovery, is a modern and vibrant city set in a stunning location at the mouth of the River Tay on the east coast of Scotland with a population of approx. 142,000.

With more hours of sunshine than any other Scottish city and an abundance of green spaces – Dundee provides an unrivalled quality of life. It is a thriving regional economic and commercial centre drawing commuters from a catchment population of 640,000 within a 60-minute drive.’

And yet, I have missed out the second paragraph from the webpage, which seems to suggest that what is really special about Dundee is that it is easy to escape from:

‘The city benefits from a central geographic location, with 90% of Scotland within 90 minutes drive. Dundee is a main station on the UK east coast line, has excellent motorway network access and a regional airport with direct flights from London. It is also a significant cruise ship port.’

The idea that Dundee is a city to escape from resonates with the story I am researching just now – the emigration of George Robertson Nicoll and his wife Sarah Baird to New South Wales in 1848 as ‘assisted migrants’. Unusually, George and Sarah returned to Dundee ten years later in 1858, and subsequently secured a second ‘assisted passage’ to Sydney in 1862. From then on, George completed the three-month journey to and from Dundee a further five times, returning in 1877, 1886 (with Sarah), 1888, 1890 and 1898. He finally settled again in Dundee in 1899 and died on holiday in the Isle of Wight in 1901.

Like most migrants, George was devoted to his homeland, which he calls ‘bonnie Scotland’, and was especially fond of the Perthshire and Angus countryside, which he writes about with great affection. He named his Sydney home Taybank, and one of his ships (built in Dundee for the coastal trade in Australia) the Lass o’ Gowrie. Yet George says almost nothing about Dundee itself, beyond expressing his reluctance to return from his stay in Perth after the shipyards there closed down in 1846. A contemporary description of Dundee from the Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal, published on 13th March 1847, may explain why he had no wish to return to what he called ‘smoky Dundee’. The author describes his short trip on the ferry from Fife over to Dundee:

‘… leaving Fife behind, we must get on to Dundee, which, enveloped in a cloud of smoke, issuing from a crowd of lofty chimneys, did not make itself visible till I was actually landed on its quays.’

This is a dreadful picture of Dundee, so what must it have been like for the people who had to live and work in such an environment? The account continues encouragingly:

‘The Dundee folk, however, as I am well informed, care little about the smoke; the great thing with them being plenty of orders for the products of their foundries, spinning mills, and factories. A sagacious, enterprising set of people, with an indomitable spirit of industry, are the inhabitants of Dundee’ (page 161).

This, then, is the reality of Dundee in the nineteenth century. During George’s lifetime, the city underwent a period of major social and economic expansion. In 1801, the population had been only 2,472, and yet over the next 50 years, it had grown to 64,704, and by 1901, it was over 161,173. The Dundee Directory and General Register records six ship-building yards in full employment in 1834, as well as three iron foundries at which steam engines and boilers were manufactured and six further ‘manufactories’ (firms that supplied all the smaller machinery for the spinning trade). A recently-completed research project on Victorian professions includes Dundee as one of its study sites. It offers this description of Dundee in the nineteenth century:

‘The export of wool in medieval times was replaced in the 18th century by the production of linen in substantial four storey-mills, supported by the 1742 Bounty Act. The phasing out of this government subsidy in 1825 and 1832 stimulated demand for cheaper textiles and the town switched to jute production, using its easily accessible supply of whale oil to lubricate the dry fibres. At its height in the 19th century, the Dundee jute industry had 62 mills, employing some 50,000 workers. This jute boom led to an expansion in the supporting industries of whaling and shipbuilding. Around 2000 ships were built between 1871 and 1881 and because of its experience building whaling ships to withstand extreme conditions, Dundee was also chosen to build the RRS Discovery which took Captain Scott to Antarctica – the last traditional wooden three-masted ship to be built in Britain. The second half of the 19th century was a period of great prosperity for the town and it is often said that Dundee was built on the three J’s: “jute, jam and journalism”.’

Another historical source states that ‘at its zenith, the harbour in Dundee sprawled over 119 acres and three and a half miles of quayside, and more than 200 ships and 18 whalers registered in Dundee traded around the globe’ (Ogilvy, 1999: 72).

Inevitably, Dundee’s industrial success did not make it a healthy place for its residents. Not only did they (particularly the women) have to contend with working 12-hour days in noisy, poorly-ventilated factory buildings, their living accommodation would have been overcrowded, with little or no sanitation and no running water. Dundee also had major social problems associated with drunkenness at this time. It was estimated that by 1888, Dundee had more public houses per head of population than anywhere in Scotland, ‘with 447 licensed premises plus innumerable shebeens selling illegal liquor’ (Ogilvy 1999: 185).

One of the things I have been trying to do is to imagine Dundee as George and Sarah would have seen it. This has proved all but impossible, not least because Dundee lost so many of its landmark buildings at two key moments: firstly, as a result of actions taken as part of the Dundee Improvement Act on 1871, and then again more recently, in the 1960’s and 1970’s, as Dundee’s crumbling city centre began to be modernised. Lamb’s Dundee, published in 1895, describes the High Street that George would have known as follows:

‘When the Town House, Trades Hall and Union Hall were all in existence in the High Street of Dundee, the place presented a very picturesque appearance, recalling the market-square of some Flemish burgh rather than the thoroughfare of a Scottish Town’ (page XII).

This early photograph, taken around 1878, captures some of the sense of this. When George was a small boy, the Nicoll family lived in rooms above the shops on the left hand side, and his Robertson grandparents lived across the road and up a bit. Only a few years later, The Trades Hall and Union Hall disappeared, removed for the purposes of road widening. The Town Hall, initially extended to the rear in 1872, was later demolished, along with St Clement’s, Dundee’s earliest parish church, to make way for the Caird Hall, built between 1914 and 1923, and the new city chambers and City Square in 1932.

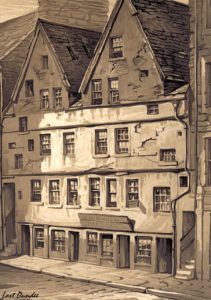

Another of Dundee’s famous buildings, reproduced by Lamb in 1895 and demolished twenty years earlier, was Our Lady Warkstairs, which stood on the north side of the High Street, opposite Crichton Street. It was, Lamb tells us, the last of the old timber-fronted houses in Dundee, standing nine stories high: ‘one of the most magnificent mansions in Dundee’ (page XXI):

George’s birthplace, Campbell’s Close, 74 High Street, Dundee still exists today, although it is well-past any grandeur it may have held in the past. The rooms at Campbell’s Close, with its wrought-iron gateway, were undoubtedly sought-after property in their day. Today, the High Street still contains some smart stores and shops, but there are also parts that are significantly down-at-heel; Campbell’s Close is now entered to the left of a garish gambling arcade full of slot machines. The close itself is unappealing and dirty, and a homeless person uses the front entrance as his begging stance:

And so my discovery? – to conclude – is that George would not know Dundee today. It is a very different city to the one he and Sarah left in 1848 and to which he returned on many occasions. Its traditional industries of shipbuilding and textiles have gone, and it has sought to re-invent itself as a centre for medical research and the digital entertainment industry, as well as being a major tourist destination, bolstered by the presence of the RRS Discovery and the recent addition of Scotland’s first design museum, the V&A. It is home to thousands of university students; one person in seven of Dundee’s current population is a student. There is, in reality, little that connects it with its past, while only fragments remain: St Mary’s Church, which was rebuilt after fire in 1844; the High School of Dundee, originally opened in 1834 as the ‘public seminaries’; Morgan Academy, established in 1866 as the ‘Morgan Hospital’; the McManus Gallery and museum, formerly the ‘Albert Institute’, founded in 1867; Couttie’s Wynd (the original through-way that connected the town centre and the harbour). And, of course, Campbell’s Close, which, I hope, may some day get the recognition it deserves as one of the few remaining closes in Dundee.

Viviene Cree

22nd August 2019.

References

http://www.victorianprofessions.ox.ac.uk

Lamb, A.C. (1895). Dundee. Its Quant and Historic Buildings. Nethergate, Dundee: George Petrie.

http://canmore.org.uk/collection/702403

It was not until the 1870’s that Dundee inhabitants were able to access clean water, thanks to the building of the new Lintrathen reservoir (Ogilvy, Graham. (1999). Dundee: A Voyage of Discovery. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing).

https://www.fdca.org.uk/1871_Dundee_Improvement_Act.html

Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal Volume VII, No. 167, https://archive.org/details/chambersedinburg7818cham/page/n173

https://www.rrsdiscovery.com/

https://www.vam.ac.uk › dundee