Every blog in this series has begun with a challenge – how to make sense of something in a way that does justice not just to what is said but also to explore what is not said. As with the other blogs, I am working through the publications (a journal from 1890 and a book published in 1899) of my Dundee forebear, George Robertson Nicoll. So I want to think about what George chooses to report and why, what he deliberately omits to tell us, and what he takes for granted and does not even notice. This blog explores George’s experiences of ‘race’ and identity – his own and others – from 1848 when he landed in Sydney with his wife Sarah and infant son, George Wallace, and 1901 when he died.

George was a white, male, Scottish, Presbyterian colonist; I am a white, female, Scottish, currently-agnostic academic, living in Scotland – very much an outsider, just as he was. I have visited Australia on three occasions, and during those times, had very little contact with Aboriginal people. In contrast, on three visits to Aotearoa/New Zealand, I was privileged to meet Māori women and men, some of whom I got to know well as they shared stories of their culture and heritage with me.[1] What does this tell us, about very different approaches to the First Nations people of Australia and Aotearoa/New Zealand? But that is another story, and it’s George’s experience that I want to foreground in this blog.

What comes across in George’s writing is the story of a man who was trying to make sense of the very different situations he found himself in. He was, at heart, ‘Scotch’, deeply proud of ‘bonny Scotland’ (Journal, page 1), its scenery, its music, its dancing, its education, its whisky! He returned here on many occasions during his lifetime and finally chose to live out his last years in Scotland. Beyond this, he liked to think of himself as a ‘good man’, God-fearing, loyal, honest and protective of the weak and vulnerable; this is the George that he wants the reader to see. But he struggles to live up to his self-image, and this produces some dissonance in his accounts of his life and adventures. At times, he comes across as genuinely sympathetic – he understands and accepts that the white man has done real harm to indigenous peoples. Yet at other times, he seems to accept cultural stereotypes without question. Through a close reading of his book and journal, and by placing this in its wider social context, we can uncover something of the complex reality of the contradictions within a white emigrant’s views of ‘race’ and identity.

Situating George’s writing in context

One of the most striking aspects of George’s journal and book is how little he mentions Australia’s First Nations people (widely known, at that time, as ‘Aborigines’ or ‘Aboriginals’).[2] Either they were so common as to not merit attention (extremely unlikely by 1848) or they simply did not feature in his world (a more likely explanation). We hear much more about his encounters with ‘savages’ in the South Seas than we do about his interactions with the indigenous peoples of Australia. And this requires further reflection.

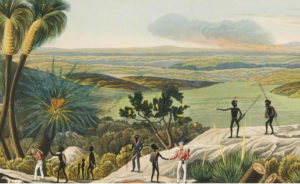

Estimates vary, but it is suggested that there were between 300,000 and 600,000 indigenous people living in Australia in 1788, at the time when the first transport ships carrying convicts arrived in Sydney Cove.[3] They had lived in Australia for some 30,000 years and were divided into more than 500 tribes, with at least 220 distinct languages. Their numbers had already been massively depleted by 1848. Not only had many been killed by conquerors’ guns, others had died from the imported diseases of pneumonia and consumption, smallpox and syphilis.[4] Tens of thousands had been forced off their traditional lands, as free settlers, assisted migrants and former convicts had cleared ‘the bush’ and destroyed forests to make way for farming. The impact of the ‘pastoral incursion’[5] cannot be overstated, as Macintyre (2009) explains:

‘[…] there was little effort to increase efficiency or conserve resources. Stock quickly ate out native grasses. The cloven hoof hardened the soil and inhibited regrowth. Patches of bare earth round the stockyards, eroded gullies and polluted water-courses marked the presence of the pastoral invader. So did the signs of human loss, the ruined habitats and desolate former gathering places of the Aboriginal inhabitants, the skulls and bones left unburied on the sites of massacres, and the names that because associated with some of them’ (page 59).

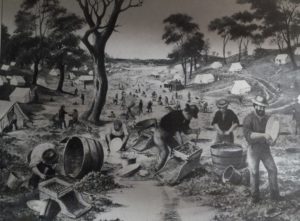

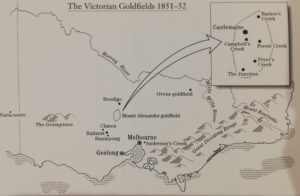

By 1848, large numbers of ‘Aboriginal’ people had been forced to far-flung mission stations and native reserves for their own ‘protection’ – protection from white settlers who shot and poisoned them and protection from each other, as rival tribes fought over land. The discovery of gold in the 1850’s was another nail in the coffin of the indigenous people of Australia, as gold digging in New South Wales and Victoria placed enormous pressure on the land and on a people whose way of life had depended upon living off, while caring for, the land.[6]

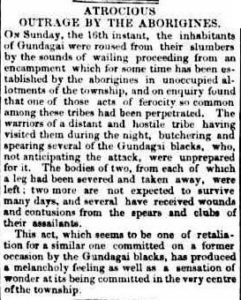

A search of local newspapers in 1848 gives a flavour of how Aboriginal people were presented at that time. In the Sydney Morning Herald, we find them convicted of stealing potatoes and sheep and killing cattle; charged with assault, rape and murder. We also find stories of ‘atrocious outrage’ like this one, as one tribe attacked another at night at Gundagai:

In contrast, there are positive stories, such as accounts of ‘our sable brethren’ providing ‘great service’ at harvest time. But two strong messages come through again and again in the newspaper coverage. Firstly, we are told that the ‘Aboriginals’ were a ‘backward’ race, ‘incapable of elevation’[7] (all attempts at ‘civilising’ them were bound to be ultimately ineffective). Secondly, we read that they would ‘soon disappear from amongst us’ (the so-called ‘doomed race theory’).[8] Both messages led to the same incontrovertible conclusion: nothing could be done, whether one showed pity for, or hostility towards, Aboriginal peoples. This was the prevailing view that George Robertson Nicoll would have inherited when he landed at Sydney in 1848.

‘Blackfellows’ in Sydney

The first mention of indigenous Australians in George’s writing appears early in his account of his travels and adventures, and it is not a favourable first impression:

‘Next day we came on shore with all our luggage and rented a small two roomed weatherboard house in Sussex Street – a dirty, damp place full of rats and blackfellows living next door nearly always drunk and noisy and singing a song with this chorus: “The world may nag, since I got the bag; for hundreds have got it before me” ‘(Journal, page 39).

This presentation of Aboriginal people as poor and drunk is a familiar one in the newspapers of the day; poverty and alcohol use remain a serious problem in indigenous communities.[9] John Pilger’s (2013) film Utopia is a damning indictment on the conditions in which many First Nations people are forced to live today.

I was unable to find the song that George refers to; it has been lost over time, along with its meaning. What was ‘the bag’ in the song. Was it ‘the sack’ (they had lost their jobs)? Or was it a sexually transmitted infection such as syphilis or gonorrhoea (both were both passed on by white men to Aboriginal women, who in turn, infected their partners).[10] Alternatively, did George misunderstand what he heard; was this actually an Aboriginal word that he was unfamiliar with? We have no way of being sure.

The next mention of Aboriginal people is a few months later, in relation to George’s trip to California as part of the 1848 gold-rush:

‘[…] we made a start. Took two Aboriginals Blacks with us, as they had better eyesight than us and would as we thought be useful to pick up the small gold specks; such was our ignorance of gold finding at the mines’ (Journal, page 47).

This is the one and only mention of these two men. We know that George and his mates failed to find gold and returned to Sydney as soon as they were able to secure their passage. But we have no idea what happened to these men. Did they manage to hitch up with other more successful diggers and make their fortunes, or as seems more likely, did they die of cold and starvation in the snow-bound country they found themselves abandoned in, without money and without support?

Later, George describes the Aboriginal people he sees at the New South Wales goldfields:

‘[…] arrived at Queanbeyan and stayed there with an acquaintance of mates and equipped ourselves with tent, tools, blankets, provisions etc., we arrived in due time and found the country hilly and very cold, well-watered with beautiful spring water on the tops of the tablelands, abundance of grass and potatoes wild, about the size of gooseberries. We dug them out with knives and boiled them. The blacks come every year for them and live on them while they last, together with kangaroo, Opossums etc., we pitched our tent on one of the hills and made ourselves as comfortable as we could. Firewood was scarce and the weather extremely cold and the ground damp’ (page 110).

This description fails to indicate that the diggers were making it extremely difficult for the Aboriginal people to live in their traditional ways. Not only were they competing for food, they were also devastating the land, polluting streams and rivers and clearing forests and bushes so that wildlife disappeared.[11] Bruce Pascoe has written a powerful riposte to the conventional presentation of Australia’s First Peoples as hunter-gatherers who lived in an uncultivated land. He argues that they planted, irrigated and harvested; they stored the surplus in sheds; they built dams, houses and villages. But they did so with a larger goal in mind:

‘Earth is the mother. Aboriginal people are born of the earth and individuals within the clan had responsibilities for particular streams, grasslands, trees, crops, animal, and even seasons. The life of the clan was devoted to continuance’ (Pascoe, 2018: 209).

What the First Nations people were faced with was the destruction of their land and culture, as the new ‘Australians’ consolidated their hold on the country. George was inevitably implicated in this process in all his activities, on the gold-fields, in forestry, in farming, and finally, in trading with settlers up and down the rivers of New South Wales. This is not, however, something that he chose to write about.

Experiencing racism first-hand

An interesting aside is that George himself experienced discrimination in San Francisco in 1848, where he and his mates were greeted with posters bearing the message: ‘NO SYDNEY MIGRANTS HERE’. As he explains:

‘[…] A deal of misery existed at this time. The Sydney people were camped at a place outside the town called Happy Valley, where they pitched their tents and erected portable wooden houses which they brought from Sydney and other parts of the colony. We came across some we knew who had arrived before us and who were at work on the streets, but they were much afraid to speak to us for fear any of the Yankees working alongside would hear we were from Sydney in which case they would be discharged or perhaps something more befall them, so we had all to say we were from New Zealand or Canada’ (page 54).

The posters illustrated the widely-held perception that all Australians were convicts – thieves and murderers – and California did not want them! Nevertheless, George does not comment on the much more widespread anti-Chinese hostility at this time, which reached a head in the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, prohibiting the immigration of all Chinese labourers.

Encounters with ‘savages’, ‘natives’ and ‘cannibals’

Returning from California early in 1849, George was shipwrecked at the Bay of Islands for some months. While he was there, he was helped by a number of locals (white men and black men, women and children), and he writes very forcefully about a ship’s captain’s double-crossing of the ‘natives’ who had rescued them.

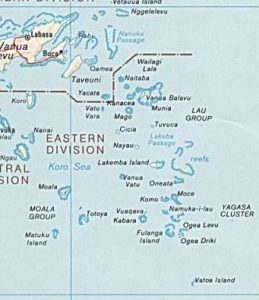

George describes his encounters with the South Sea Islanders in great detail. He admired the ‘natives’, whom he describes as big and strong, although sadly lacking in clothes (he saw this as a marker of how ‘civilised’ they were). He was especially relieved to be advised that he and his fellow sailors had been ‘tabooed’ – they were not to be eaten! His account includes the following stories:

‘[…] we were in great suspense, when a native came on board. He was very big man, a regular giant. He said nothing but took up my blanket, which I had saved, and a tommy hawk. He placed the blanket over his shoulders and with the axe in his hand sat in the bow of the boat staring at us and waving the small axe for about two hours. He brought neither coconuts nor anything with him and we were in a sad plight to know what was up. In the meantime we were showing off two rusty red flint guns which were no use as we had no powder but thought they might frighten the savage […] the savage plunged in the sea and swam off with blanket and tommy hawk. Nothing occurred until daylight when a native swam to us with some young coconuts tied around his neck and, as this was a sign of peace, we lifted the kedge and went into the beach with the boat (Journal, pages 62-3).

The story continues:

‘We now spread our clothes out on the grass to dry. As soon as they were laid out however, they were all stolen. I saved nothing but what I had on, a shirt and pair of trousers. The natives now came to us in scores, men, women and children. We had saved a saucepan or two and took possession of an empty hut. The cook caught a sea turtle and made some turtle soup for our dinner. There were two natives here from Tonga who were building a canoe and who had been among the missionaries and were now trying to connect the natives. They came to us and made signs that we were to be tabooed. That is, not to be hurt by the natives’ (Journal, page 64).

He then travelled to another island where he lived for a few weeks with a ‘Yankee’, who had a ‘black wife’ and a ‘black man slave and black woman slave’. George describes his shock at the treatment of the black woman slave:

‘One morning his female slave forgot to put the salt on the table for our eggs, he called his tall man and told him to get the whip and bring the female slave to the door of the kitchen, tie her to the post and whip her on the bare back, for that small offence, or rather mistake, in order to show us what he could do and what power he had over these poor creatures. This cruelty interfered very much with our digestion. We had previous to this learnt from him by conversation that he had been colleged in Salem, South America. His father was a clergyman and owned several slaves and said that there was no more pain in that than whipping a horse. After this he fell very much in our estimation’ (Journal, page 68).

George continues:

‘At this time, a white wishing to settle on any of these islands could buy a male or female servant from the chief for about 10/- of trade, such as a cheap gun. The chief would also build him a Fijian house for the same amount. The few whites who were living on these islands got their wives and servants through the chiefs in this way. The wives and servants do all the work, build the houses, plant yams, catch fish, dig the yams, cook, wash etc. The black men do only as they fancy. They make the canoes and implements of war and do any fancy work etc. as well as go to the wars’ (Journal, page 69).

He also writes very critically about missionaries and the harm they had done in the South Sea Islands. His observations are telling:

‘As far as I have seen and heard, it is my opinion that the white missionary has a splendid time of it and may come home to England in less than twenty years with a handsome fortune. However, if they would only send home true reports about the grand life they have they could be forgiven as it is a great shame that the poor people in England and throughout the British Empire should be induced to give so much of their hard earnings away under the cloak of converting the poor heathen. It is all a great mistake for the “poor heathen” in the South Sea Islands are far better fed that the British poor with the advantage of having no work to do, as a rule they are far happier before the missionaries come among them, for they afterwards know the use of money, strong drink, tobacco and vice of which they were innocent before. The money however that is collected for the poor heathen never reaches them, the missionaries agents, presidents, secretaries and other officials, eat it all up in grand style but the “poor heathen” does not want it, they themselves say – feed your own poor in your own country, for missionary eat it all (Journal, pages 72-3).

It is noteworthy that George does not describe the mission stations and native reserves in Australia in the same way; it seems he had no contact with them. Nor does he comment on the notoriously racist Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act, which was first passed in Queensland in 1897, and followed in Western Australia in 1905, Northern Territory in 1910 and South Australia in 1911.[13]

George finishes the account of his shipwreck by introducing another story of an inter-racial marriage:

‘Among the whites was a Scotch chap from Montrose, who had the share of a small boat. He had a black wife and black slave, had a family of children and some goats and fowl. I asked him if he would not like to leave the island. He said no, never. I am happy, get a good living, am my own master and can do as I like, with no rent, taxes or wages to pay, with plenty to eat and drink. We also bade adieu to our host and black Nancy, his wife, as well as the other whites and darkeys who were so kind to us. We felt as if we were parting from friends’ (Journal, pages 77-8).

This is the George he wants us to see – open, accepting, non-racist.

Later years

There is no other mention of black or First Nations people at any point in the rest of George’s narrative of his life and adventures in Australia. In his final years, he travelled the world as a tourist almost non-stop, and he provides vivid accounts of his trips to mosques, temples and churches, to museums and burial sites, to shops and schools. He also visited World Fairs on three occasions, in Paris in 1889, in 1893 and 1895 in Chicago, where he would have seen displays of First Nations’ peoples, seen at the time as educational, not controversial in any way.[14]

In all this writing, George comes across as someone who was interested in how other people lived their lives, open to difference, with a curiosity and lively intelligence. He was not obviously racist in any way. But maybe that is not the point. George benefited from the privilege of his own gender, ‘race’ and culture. As Satnam Virdee (2019) points out, racism works through ‘multiple routes’; it is ‘incremental’ and ‘relentless’:

‘It is only through concretisation that we can demonstrate the interplay among causal mechanisms, idiosyncratic events as well as powerful contingencies. In that process, we can illuminate what work racism accomplished across time and place as well as for whom and why’.[15]

George Robertson Nicoll was a man of his’ time and place’. His story is both unique and, at the same time, symptomatic of this wider reality. He was, at the end of the day, a British coloniser, complicit in the imperial project. Two of his sons went on to become prominent politicians: George Wallace Nicoll at local level as an Alderman in Canterbury, Sydney and Bruce Baird Nicoll at state level as the Protectionist member for Richmond on the New South Wales Legislative Assembly (M.L.A.) between 1889 and 1894. Both men were ‘Federationists’, proud Australians who supported the coming-together of the six self-governing colonies of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia, and Western Australia into the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901. Bruce was also a Protectionist, and as such, would have been sympathetic to the ‘white Australia’ policy as outlined in the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901, which outlawed the immigration of non-Europeans, specifically Chinese people and Pacific Islanders.

As George’s descendant and a British person, I have benefited both from his individual achievements and from the imperial colonising project in general, just as I currently benefit from my own privileges of class and ‘race’ every day of my life.

Viviene Cree

20th January 2020

Primary Sources

Nicoll, George Robertson (1890). The Life and Adventures of Mr George Robertson Nicoll, unpublished journal.

Nicoll, George Robertson (1899.) Fifty Years’ Travels in Australia, China, Japan, America Etc. London: self-published.

References

Cree, Viviene E. (ed.) (2013). Becoming a Social Worker, Global Narratives. London: Routledge. ISBN 978 0 4156 6694 7

Macintyre, Stuart (2009). A Concise History of Australia. 3rd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pascoe, Bruce (2018). Dark Emu. London: Scribe Publications UK Ltd.

Ritchie, John (1975). Australia As Once We Were. Melbourne: Heinemann.

Further reading

Attwood, Bain (1989). The Making of Aborigines. Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Docker, John and Fischer, Gerhard (eds) (2000). Race, Colour & Identity in Australia and New Zealand. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

Elkin, A.P. (1945). The Australian Aborigines. How to Understand Them. Sydney and London: Angus and Robertson Ltd.

Evans, Raymond, Saunders, Kay and Cronin, Kathryn (1988). Race Relations in Colonial Queensland: A History of Exclusion, Exploitation and Extermination (Second edition) Brisbane: University of Queensland Press.

Evans, Raymond (1999). Fighting Words. Writing about Race. St. Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press.

Kidd, Rosalind (1997). The Way We Civilise: Aboriginal Affairs – The Untold Story, St Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland Press.

Loos, Noel (1982). Invasion and Resistance: Aboriginal-European Relations on the North Queensland Frontier, 1861–1897, Canberra: Australian National University Press.

Macmillan, David S. (1967). Scotland and Australia 1788-1850. Emigration, Commerce and Investment. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Richards, Eric, Reid, Richard and Fitzpatrick, David (1989). Visible immigrants, Neglected Sources for the history of Australian Immigration. Canberra: Dept. of History and Centre for Immigration and Multicultural Studies, Research School of Social Sciences, Australian National University.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai (1999). Decolonizing Methodologies. Research and Indigenous People. Dunedin: University of Otago Press and Zed Books.

Endnotes

[1] For more information, see chapters written by Moana Eruera and Gaylene Stevens in Cree (ed.) (2013).

[2] To find out more about the various terms given to Australia’s First Nations people, see https://www.commonground.org.au

[3] Ritchie, 1975 page 26; Macintyre, 2009 page 61.

[4] See Campbell, Judy (2002). Invisible invaders: smallpox and other diseases in Aboriginal Australia, 1780-1880. Carlton South, Vic: Melbourne University Press.

[5] Sheep numbers increased from 100,000 in 1820 to 1 million in 1830, and while the production of other livestock and cereal crops also increased sharply, it was sheep that were ‘the shock troops of land seizure’ (Macintyre, 2009: 58). New South Wales flocks numbered 4 million in 1840 and 13 million in 1850.

[6] See my previous blog for a fuller t of the negative impacts of gold digging. https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/emigration-blog/2019/12/21/nothing-but-gold/

[7] See Westgarth, William (1948). Australia Felix, Historical and Descriptive Account of Port Philip, Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd.

[8] See McGregor, Russell (1997). Imagined Destinies. Aboriginal Australians and the Doomed Race Theory, 1880-1939. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. It was this idea that led to the conclusion that aboriginal children should be taken from their mothers (both so-called ‘half-castes’ and ‘full-blooded’ children) and placed with white families for their own ‘protection’; they have been called the ‘stolen generation’. See https://aiatsis.gov.au/research/finding-your-family/before-you-start/stolen-generations/

[9] Study reported in the Guardian newspaper, 20th February 2015. See https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2015/feb/20/alcohol-abuse-behind-high-rates-of-early-death-among-indigenous-study-finds/ For more recent research, see Lee, K.K., Conigrave, J.H., Wilson, S. et al. (2019). Patterns of drinking in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as self-reported on the Grog Survey App: a stratified sample. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 19, 180. doi: 10.1186/s12911-019-0879-8

[10] See Dowling, Peter J. (1997). ‘A Great Deal of Sickness’: Introduced Diseases among the Aboriginal People of Colonial Southeast Australia. Unpublished PhD thesis, Australian National University, Canberra.

[11] See my previous blog for a fuller account of the negative impacts of gold digging. https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/emigration-blog/2019/12/21/nothing-but-gold/

[12] Although cannibalism was practised in a number of the islands at this time, white people (and missionaries) were treated as ‘taboo’ (ref).

[13] This legislation established reserves to which Aboriginal people could be forcibly taken and removed their civil rights, treating them as dependents rather than citizens. The Act was strengthened by subsequent amendments.

[14] Such displays were a common feature at the fairs. There has been much debate about how far this was degrading and exploitative, and to what degree Native Americans, for example, were able to use these displays as an opportunity to represent themselves in an authentic way. See Beck, David R.M. (2019). Unfair Labor?: American Indians and the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

[15] Satnam Virdee, Unthinking Sociology and Overcoming its History Deficit, The Sociological Review Annual Lecture, 18th August 2019, available on Youtube: https://youtu.be/sKfbMBphsYg