This is the last in the year of blog-posts that have followed the emigration of my forebears, George Robertson Nicoll and Sarah Baird Nicoll, on their life journeys from Dundee in Scotland to New South Wales in 1848. I have learnt a great deal along the way: about my home city of Dundee, about emigration, about gold-digging and farming, about house-building and coastal shipping in New South Wales. I have also learnt that emigration is unlikely to be a one-off experience; George and Sarah returned ‘home’ on a number of occasions, and their ties with ‘home’ remained strong throughout their lives. Towards the end of his life, George came ‘home’ ‘for good’; Sarah had died a few years’ earlier in Sydney. Their children saw themselves as Australians through-and-through, and it is to them that we must look to see the real consequences of the emigration journeys of their parents.

But for now, it is time to look back and also to look forward, to think – what next for this story?

Looking back over the last year

When I began writing the blog in April 2019, I had read George’s book (published in 1899) but not his journal, which ends in 1897. I was hopeful that sharing his story would shed light on emigration as a personal, social and cultural journey, but, if I am honest, I was not at all sure how this might happen. In the event, I needn’t have worried. George’s book and journal, in many ways, spoke for themselves; it was George’s words that captivated readers of the blog, just as they had captivated me. It did not matter that George was my relative; readers from across the world identified with his stories because George was, in a sense, ‘everyman’, at the same time as being a unique individual, with his own history and his own foibles. And yes, he had plenty of them! George was not only courageous, resourceful and insightful; he was also self-opinionated and, at times, downright arrogant. But all of this contributes to the colour and vibrancy of his writing, and in the blog, I tried to share George with readers, ‘warts and all’.

So if George was indeed ‘everyman’, what ‘everyman’ was he? In the blog, I sought to connect George’s account with the larger stories of the day – stories which began in the early nineteenth century, as Scotland emerged from its agrarian past to become one of the major industrialised nations of the day. George and Sarah were, to a large extent, therefore, Dundee – he, the blockmaker who worked at the harbour; she, the mother and linen powerloom weaver who worked in a factory. The story of their migration is the story of every successful migrant that left Scotland for the new worlds in the nineteenth century; in the words of Anthony Trollope (1873):

In the colonies those who make money are generally Scotchmen.[i]

Once in New South Wales, George became the ‘everyman’ who chased the lure of gold, just as Sarah was the ‘everywoman’ whose lot was defined by choices made by her husband and the father of her children. This didn’t make George a bad husband or father, any more than Sarah was a victim without agency. Both were people of their day and time, and their triumphs and defeats say as much about the human condition as they do about themselves as individuals.

But that is enough from me!

It seems that towards the end of his life, like many emigrants, George came ‘home’ to Scotland ‘for good’. I would now like to consider this more deeply in the context of his book and journal, at the same time reflecting on the wider literature on emigrant homecomings.

Return migration

Between 1825 and 1939, 2.3 million Scots left Scotland; if we add to this the number of people who moved from Scotland to England, ‘Scotland might well be described as the migration capital of the Continent at this time’ (Devine 2011: xv). Many of those migrants – estimated at between one-fifth and one-third – returned to their homeland, either sooner or later (op.cit.). Meanwhile, the number of British migrants returning from Australia in the period 1870 to 1914 was even higher. Baines (1985) estimates that around 40 per cent of all those who emigrated in the mid-nineteenth century returned home. These people, Richards (1989: 17) argues, ‘remain virtually invisible and anonymous’.

A wide variety of terms have been used to describe the phenomenon of return migration, including remigration, second-time migration, homeward migration, back migration, re-emigration etc. (Verrochio, 2011:1). George Robertson Nicoll’s story, as we will see, reminds us that it is impossible to discuss return migration as if it were one thing. As we will see, individual and structural issues came together in the decisions both to migrate and to return; this shows that emigration and return are governed by happenchance as much as by design.

The first emigration, 1848

George and Sarah’s first emigration on the Royal Saxon happened because a number of ‘push and pull’ factors came together at a particular moment in time:

- The economic downturn in Dundee in the 1840s

- George’s experience of being the youngest son

- The death of his mother and his father’s remarriage

- The birth of George and Sarah’s first child

- The failure of George’s elder brothers’ business

- George’s skills, self-belief and entrepreneurial qualities

- The promise of a better life and opportunities

- The chance of an ‘assisted passage’ to New South Wales (see blog 6).

The first return home, 1858

Their decision to return to Scotland ten years later in 1858 was also as a result of a number of coalescing factors:

- Sarah’s poor health and medical advice to return to a cooler climate

- The educational needs of the children

- George had failed to make a living as a farmer

- George and Sarah had, nonetheless, enough money saved to travel to Dundee and to set up home when they got there

- They also had family support back in Scotland.

George stayed in Scotland for only six weeks at this point, and went back to the goldfields, leaving Sarah and their five children in Dundee. When he returned three years later in July 1861, he had, he tells us, ‘the intention of […] settling for good in Scotland’ (1899: 68). But life (and the Scottish winter) intervened to make him change his mind. He writes:

It was now winter. I endeavoured to bear with the cold weather until February, all the time suffering acutely with rheumatics, toothache, headache etc. I never felt well, and could not suffer it any longer. I made up my mind to go off to Australia – the Sunny South – and took passages for all of us in the ship Hotspur from London to Sydney (page 69)

What did Sarah feel about this? The two youngest children had died from whooping cough and scarlet fever the previous year in Dundee; one can only guess that she was heart-sick of Dundee and open to persuasion (see blog 8). Moreover, George had had recent success at the goldfields, and had, surprisingly, been able to secure a second ‘assisted passage’ for the family back to Sydney.[1]

The second emigration, 1862

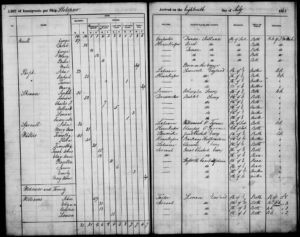

The 98-day journey from Plymouth on the Hotspur was no less demanding than the first emigration ship, and this time, George and Sarah had three children to entertain, and Sarah was heavily pregnant. There were 398 immigrants on board, along with a crew of 49 men. Three people died on the voyage, and three babies were born, including a son for Sarah and George, whom they named John Baird Nicoll.

I believe that 1862 was the time – that is, 14 years after the first migration – that the Nicoll family could reasonably be described as having ‘settled’ in New South Wales. Over the next 20 years or so, George made a successful living in the coastal shipping business (as a produce agent and later ship-broker) and in house-building. He returned to Scotland in 1877 to have a steamer built for the Manning River trade, but this trip was envisaged as a temporary visit; it was not in any sense a return migration. Meanwhile, George and Sarah’s children – only one of whom had been born in Scotland,[2] were proud Australians. Their eldest sons, George Wallace Nicoll and Bruce Baird Nicoll, became business leaders and politicians in Brisbane and Sydney; they contributed to the development of the Australian federation. Their daughter, Mary Baird Wigmore, put down long-lasting roots in the Ballina area, where she lived with her business-man husband, William.[3] Between them, they each played their part in the creation of the next generation of Australians; George Wallace, Bruce Baird and Mary Baird had 20 children, and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren besides.

The second return home, 1885

In 1885, when George was 61 and Sarah was 62 years of age, they decided to sell up and travel to Scotland. As George writes, ‘we sold off all our effects and took passage in a New Zealand mail boat, the SS Tongariro, for London’ (1899: 71).

This was not yet, however, a return migration in the fullest sense. It was a holiday; Sarah’s first visit to Dundee since 1862 (as George explains in his journal). Their adult children were now grown up and no longer needed them, and their youngest son had recently died in Sydney, aged just 18 years. They needed a change of scenery, so they travelled back to Dundee and spent the next 10 months in Scotland, staying with relatives and visiting old haunts.

The third emigration, 1887

In early 1887, George and Sarah travelled back to Sydney on another New Zealand royal mail steamer, the SS Rimutaka.

In his journal, George tells us that he felt very ‘unsettled’ to be back to Sydney. He realised it was going to be difficult to get back into the coastal shipping business again, because ‘competition was very keen’ (1890: 117). He turned his attention instead to house-building, and ‘built four new houses in the city, which occupied my time’ (1899: 74). Once they were completed, he decided ‘to have another trip to Scotland, by way of the Suez Canal’ (1899: 75).

Tourist travel, 1888-1898

The trip to Scotland in 1888 marked the beginning of a period of 10 years or so when George was in almost constant motion, travelling around the world twice and other travel besides, sometimes taking other family members with him (including his son, George Wallace Nicoll, daughter-in-law and various nieces), and other times travelling alone. He visited Scotland at least three times over this period; it is difficult to be clear about this from his written accounts. Sarah did not accompany him on these later voyages; she stayed at home in Sydney with her son Bruce Baird Nicoll, his wife and her grandchildren, dying there in August 1897.[4]

We know from Sarah’s obituary[5] that George did not attend her funeral, and I have not been able to work out why, although two possible explanations present themselves. George may have been too unwell to attend. He had had an accident the previous year, and this had left him in great pain and discomfort. When running to catch a ferry after a trip to Neutral Bay, he had missed his footing and ended up in the harbour. He had to wait some time for the next ferry, which, he writes, ‘discomforted’ him greatly:

Unfortunately, as an after effect, I was attacked with acute rheumatism in the shoulders, arms, hips, and left leg. I could not raise my arms to their full extent without experiencing the most acute agony. Walking was slow and painful work to me, and even writing was a torture. I had to keep indoors for some time, and thus neglected my business, and when I did get out again it was with no little danger to myself, for I would suddenly have terrible twinges of pain, which would compel me to slacken my pace; thus it happened I escaped by the merest chance being run over by an omnibus. I was crossing right in front of it, at quite a safe distance under ordinary circumstances, when one of these sudden pangs of pain gripped me as in a vice, and I could not proceed. It was with the greatest difficulty I got out of the way of the bus, and had the driver not done his best, I should have been knocked down by the bus.[6]

Was this fibromyalgia, a chronic, incurable condition triggered by the shock,[7] or was it something else? Given that his three elder children all died unexpectedly young (at 52, 54 and 56 years of age), and given that both his sons described having similar accidents, I wonder if there was another explanation? George’s death certificate cites cause of death as ‘chronic bronchitis (two years) and cardiac failure’. Was this accident the first indication that George had heart disease, and was there perhaps a congenital aspect to this? We will return shortly to George’s final years, but for now, we can only guess that George may have been too ill to attend Sarah’s funeral, and this may also explain why he stopped writing his journal and book the previous month, in July 1897.

There may, of course, be an alternative explanation, one for which I have, as yet, found no documentary evidence. It is possible that George and Sarah were estranged by 1897. They were not formally divorced, but they seem to have been living apart. When George and his niece Sarah (brother James’s daughter) travelled to Sydney earlier in 1897, they had lived for three months in a rented cottage at Strathfield, then a desirable suburb of Sydney, rather than at Gordon, with Sarah, son Bruce and his family.

George’s book continues a little further than the journal, and ends with a description of another trip back home in July 1898. He concludes with the words:

Thence we steamed on to London, via Plymouth, and arrived at the docks safely, after a fine passage from Port Said. Which brought me back to Old England once again, and a convenient proximity to the Land of Scots (1899: 224).

Home ‘for good’, 1900-1901

George must have returned to Sydney one last time, but I have not yet found any record of this. What we do have, however, is a newspaper story from 20th March 1900, which states:

Mr. G. R. Nlcoll, an old colonist of over 50 years’ standing, was amongst the passengers by M.M. Armand Behic at noon yesterday. Mr. Nicoll, who is 75 years of age, is proceeding to Scotland, his native land, where he intends spending the rest of his days. He has made the trip across some 20 times. He was one of the first owners of coastal vessels In New South Wales — a business developed later on by his sons, Messrs. G. W. and B. B. Nlcoll.[8]

The Armand Behic was described in a story in the Sydney Morning Herald some years earlier as ‘the most beautiful steamship that ever left Marseilles’.[9] I believe that George, travelling first class, would have been in his element!

And yet, what if George was actually coming home to die? We know that he was in poor health and a lot of pain. His obituary in the Sydney Morning Herald supports this claim. It states:

… failing in health four years since he determined to try the climate of Scotland, but he was unable to survive the severity of last winter.[10]

Assuming that George arrived back in Scotland in the summer of 1900, where did he spend the last nine months of his life? I have found no evidence that he bought a house when he returned, so it seems likely that he would have lived with one or other of his nephews or nieces and their families in Dundee – in Peddie Street, Craigie Terrace, Victoria Street or Windsor Street, or perhaps at Derby Terrace (Sandyford Street) in Glasgow.

George subsequently died on 4th April 1901, at Ventnor, on the Isle of Wight. My immediate thought in finding this out was, ‘lucky old George, on holiday again!’.

But I was wrong. Ten days before he died, George made a will in which he left his Dundee property and savings held in a Scottish bank to his unmarried nephews and nieces (all named)[12]. The will was witnessed by his doctor and nurse, Dr Harold Frederic Bassano[13] and Mary Hill. George was so weak, he was unable to sign the will, and instead marked his name with a cross. What a sad ending for such an articulate man! George’s death certificate provides further information. Here we learn that his 29-year old niece, Sarah Douglas Nicoll (who had travelled with him to Sydney in 1897), had accompanied him on his trip to Ventnor, and was present at his death..

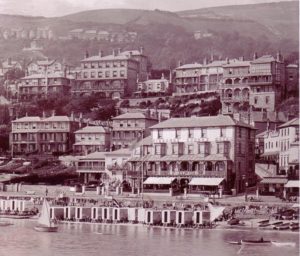

Digging a bit deeper, I discovered that at the end of the nineteenth century, Ventnor had become fashionable as a health resort . Numerous hotels and guest houses had sprung up at this time targeting sick visitors, particularly during the winter.[11]

So it was clear that George was not a tourist after all – or not only a tourist – he was sick and seeking relief from chronic pain and disability. His niece Sarah may have been his carer. And that all feels very different …

What next for this story?

I am privileged to have a connection with this amazing story, and I wondered for a while if I might try to turn it into a novel or a screenplay, but that will have to be left for someone else. Instead, I would now like to write this up as a book. There is so much to be learned from the story of George and Sarah and their lives and adventures.

All that remains is for me to thank all of you who contributed to the blog in some way. I appreciated having the benefit of your genuine interest, your knowledge and your skills and your enthusiasm. So, on with the book proposal!

Viviene E. Cree

19th March 2020

Primary Sources

Nicoll, George Robertson (nd). The Life and Adventures of Mr George Robertson Nicoll, unpublished journal.

Nicoll, George Robertson (1899.) Fifty Years’ Travels in Australia, China, Japan, America Etc. London: self-published.

References

Baines, Dudley (1985). Migration in a Mature Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Cited in Richards (1989).

Devine, Tom (2011). Foreword. In Varrichio, Mario (ed.) Back to Caledonia. Scottish Homecomings from the Seventeenth Century to the Present. Edinburgh: John Donald: xv-xvi.

Donnachie, Ian (1992) The making of ‘Scots on the Make’: Scottish settlement and enterprise in Australia, 1839-1900. In Devine, T.M. (ed.) Scottish Emigration and Scottish Society. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers Ltd: 135-153.

Freeman, Michael (2014). Ventnor. Isle of Wight. The English Mediterranean. Ventnor: Ventnor & District Local History Society.

Richards, Eric (1989). Annals of the Australian Immigrant. In Richards, Eric, Reid, Richard and Fitzpatrick, David (eds) Visible Migrants. Neglected Sources for the History of Australian Immigration. Canberra: Department of History and Centre for Immigration and Multicultural Studies, Australian National University: 7-22.

Richards, Eric (2005). Running home from Australia: intercontinental mobility and migrant expectations in the nineteenth century. In Harper, Marjory (ed.) Emigrant Homecomings. The Return Movement of Emigrants, 1600-2000. Manchester: Manchester University Press: 77-104.

Further reading

Cage, R.A. (ed.) The Scots Abroad. Labour, Capital and Enterprise, 1750-1914. London: Croom Helm.

Devine, T.M. (2011). To the Ends of the Earth. Scotland’s Global Diaspora, 1750-2010. London: Allen Lane.

Jupp, James (1991). Immigration. Australian Retrospectives. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Prentis, Malcolm. D. (1983). The Scots in Australia. A study of New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland, 1788-1900, Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Richards, Eric (2004). Britannia’s Children Emigration from England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland since 1600. London: Hambledon and London.

Sherrington, Geoffrey (1980). Australia’s Immigrants, 1788-1988. The Australian Experience. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Endnotes

[i] Trollope, Anthony (1873) Australia. Cited in Donnachie (1992: 135).

[1] Richards (2005: 90) calls those who secured a second assisted passage ‘double migrants’. He points out that until the Australian shipping lists have been fully computerised, it will not be known how many were in this category.

[2] Only George Wallace Nicoll was born in Scotland.

[3] Mary’s obituary notes that she was ‘well known by acts of charity’, while William was ‘one of the old pioneers’ and ‘one of the founders of the town’ [of Ballina]. See ‘Death of Mrs W. Wigmore’, Northern Star, Monday 9 April 1906, page 3. Accessed 2 April 2019.

[4] Bruce Baird Nicoll owned a number of properties in and around Sydney. He and his family seemed to spend most of their time at Gordon, Palace Street, Petersham; George also lived there in the 1890’s.

[5] The write-up in the Australian Star, Monday 9 August page 7, lists three sons and six grandsons who attended the funeral.

[6] Entitled ‘A SYDNEY MAN’S IMMERSION’, Evening News (Sydney) Saturday 22 July 1899 page 3. The story was covered in 47 other regional newspapers throughout New South Wales and Victoria.

[7] Medical advice from GP consultant/friend on this and all medical conditions discussed in the blog. See also NHS website information, https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/fibromyalgia/ Accessed 13 October 2019.

[8] Entitled ‘Departure of an old colonist’, Daily Telegraph, Sydney, Tuesday 20 March 1900, page 4.

[9] Sydney Morning Herald, Wednesday 9 March 1892, page 6.

[10] Sydney Morning Herald, Wednesday 29 May 1901, page 6.

[11] Freeman (2014).

[12] There is no detail as to what property this refers to.

[13] By 1911, Harold F. Bassano M.A., M.B., B.V. Cantab. was medical officer at St. Catherine’s Home for Advanced Consumption (H.R. & I.H. The Duchess of Saxe-Coburg Gotha (Duchess of Edinburgh), patron), Grove Road, Ventnor. See Kelly’s 1911 Directory, https://www.bartiesworld.co.uk/directory_db/diroutput.php/ Accessed 16 March 2020.