It looks like time to say farewell to the Decameron. The Decameron has been the place for new thinking, observation, letters from friends and art and we’ve been very proud of that. We’re now closed to new posts but if you want to get in touch please email me, angus.bancroft@ed.ac.uk

Author: Angus Bancroft

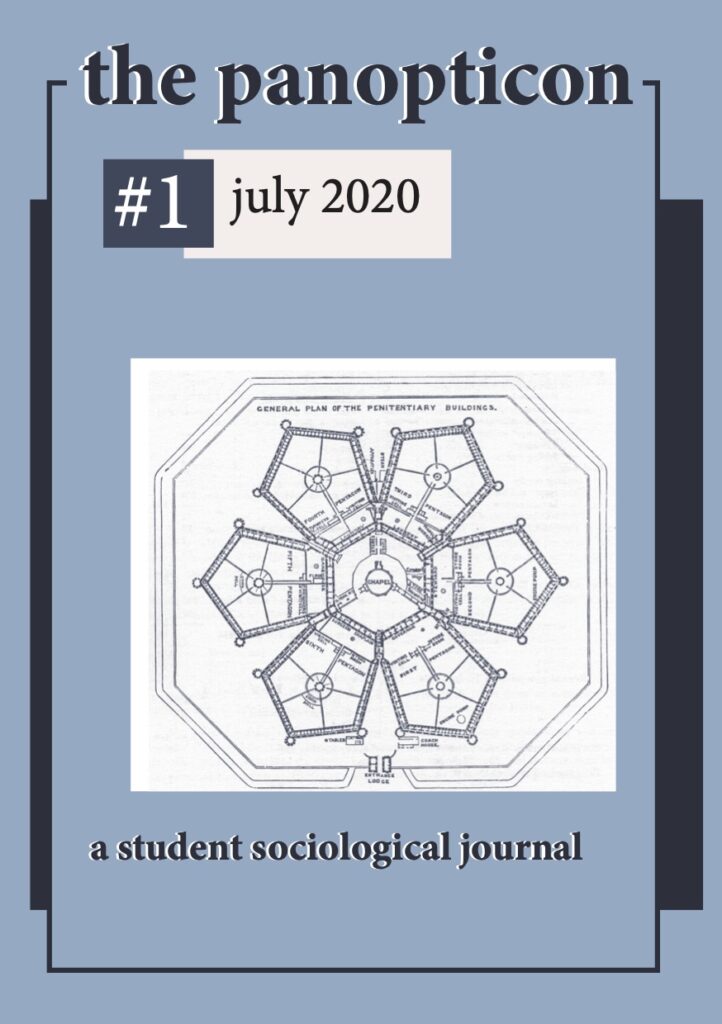

Introducing The Panopticon

I’m delighted to post the inaugural edition of The Panopticon, Edinburgh’s student led sociological journal. The Panopticon is named after the all seeing institution designed by Jeremy Bentham in the 18th Century. It is a building in which the inmates can be continually visible to their overseers. They can never be sure they are not being watched. It is an idea as much as an architectural template. Michel Foucualt identified it as the model for a pervasive system of governance and behavioural control that characterises modern societies.

The journal is a lively and fresh take on sociology and reminds us why it is relevant to the current moment. It includes interviews, playlists, reflection and analytical articles. The authors apply their sociological imagination to themes of death, anonymity, ambiguity, life in the city, system change and stasis, economics, autonomy and avacados. Thoughtful, provoking and vibrant, it asks what sociology means to us at this time, as individuals, scholars and communities. This first edition is a cracking read! Download the pdf here:

Introducing Radhika Govinda’s Rainbow Series

We are delighted to introduce the first in a seven part series by our colleague, senior lecturer and artist Radhika Govinda. Inspired by the handmade rainbows that children put up on the windows of their homes across the UK, the Rainbow Series by Radhika Govinda is a set of seven blog posts, through which she shares artwork she has been doing to grapple with the feelings and thoughts that the ongoing pandemic has brought up in her. These range from concerns about the climate crisis, to slowing down, prioritising loved ones, foregrounding radical kindness and solidarity in our quest for a covid-19-free future.

Day 1 – ‘Anthropocene’ https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/ed-decameron/rainbow-series-day-1/

Day 2 – ‘Spring is Here’ https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/ed-decameron/rainbow-series-day-2/

Day 3 – ‘Empathetic Elephants – Non-Human Roads to Kindness and Harmony’ https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/ed-decameron/rainbow-series-day-3/

Day 4 – ‘Out of the fishbowl!’ https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/ed-decameron/rainbow-series-day-4/

Day 5 – ‘Awesome Ants and the Why-Why Girl’ https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/ed-decameron/rainbow-series-day-5/

Day 6 – ‘The Squirrel’s Message’ https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/ed-decameron/rainbow-series-day-6-the-squirrels-message/

Day 7 – ‘The Peacock and the Path to New Beginnings’ https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/ed-decameron/rainbow-series-day-7-the-peacock-and-the-path-to-new-beginnings/

Read about Radhika’s work at her webpage http://www.sps.ed.ac.uk/staff/sociology/radhika_govinda and follow her on Twitter @GovindaRadhika https://twitter.com/GovindaRadhika

Thanks to Martin Booker for formatting the series for WordPress.

Fake times and real life during the pandemic

By Angus Bancroft

One of the effects of our arm’s length social life is that we interact with a limited range of interactional cues: our subconscious interpretation of body language, eye contact, tone of voice, is heavily truncated by the technology. There are many implications of that, not least for how we teach and engage students. They will have little sense of teachers and themselves as a classroom presence. It also has caused me to reflect on how we use these cues and others’ reactions for information verifiability. A part of my research is investigating how fake news and disinformation campaigns are produced and valued in the marketplace.

Disinformation operations are deliberate attempts to undermine trust in the public square and to create false narratives around public events. Rid (2020) outlines three key myths about them: 1. They take place in the shadows (in fact, disclosing that there is an active campaign can be useful to those running it) 2. They primarily use false information (in fact they often use real information but generate a fake context) 3. They are public (often they use ‘silent measures’ targeting people privately). Research indicates that how others respond to information is critical in deciding for us whether it is factual or not (Colliander, 2019). Social media platforms’ ability to counter the influence of fake news with verification tags and other methods are going to have a limited effect, other than enraging the US President.

Overall disinformation operations are about the intent, rather than the form, of the operation. For that reason tactical moves like disclosing an operation’s existence can be effective if the aim is to generate uncertainty. According to Rid (2020) what they do is attack the liberal epistemic order – the ground rock assumptions about shared knowledge that Western societies based public life on. That facts have their own life, independent of values and interests. Expertise should be independent of immediate political and strategic interest. That institutions should be built around those principles – a relatively impartial media, quiescent trade unions, autonomous universities, even churches and other private institutions, are part of the epistemic matrix undergirding liberalism.

It doesn’t take a genius to work out that this order has been eroded and hollowed out from multiple angles over the past decades by processes that have nothing to do with information operations. Established national, regional, and local newspapers have become uneconomic and replaced with a click-driven, rage fuelled, tribalist media. Increasingly the old institutions mimic the new. Some established newspapers evolved from staid, slightly dull, irritatingly unengaged publications to an outrage driven, highly partial, publication model. The independence universities and the professions once enjoyed has been similarly eroded by the imposition of market driven governance on higher education, the NHS, and other bodies. On the other hand Buzzfeed evolved in the opposite direction for a time. It also doesn’t take a genius to note that the liberal epistemic order was always less than it was cracked up to be, as noted by the Glasgow University Media Group among others.

The erosion of this may be overplayed – for example, most UK citizens still get their news from the BBC. however survey data notes that there is a definite loss of trust in national media among supporters of specific political viewpoints (Brexit and Scottish Nationalism being two). The liberal epistemic order was therefore neither as robust, nor agreed, nor as liberal as it proclaimed itself to be and may have been contingent on a specific configuration of post-WW2 Bretton Woods governance. We can see plenty of examples of where this faith in the impartiality of institutions was never the case e.g. widespread support for the Communist parties in Italy and France, which had their own media, trade unions and social life.

Building an alternative reality was a key aim of progressive movements at one time. Labour movements often had their own newspapers, building societies, welfare clubs, shops and funeral services. Shopping at ‘the coppie’ (The Co-Op) said a lot about one’s belonging, social class and politics. That alternative reality can be the basis for social solidarity. That isn’t to compare the two. Fake news is inherently damaging to any effort to build a better society or understand the one we are living in. But real life and life organised independently does provide a defence and a basis for building a resilient post-pandemic society. Part of this is resisting and questioning what underlies fake news – the continuous attack on autonomous knowledge and Enlightenment values which have eroded the resilience of democratic societies.

References:

Colliander J (2019) “This is fake news”: Investigating the role of conformity to other users’ views when commenting on and spreading disinformation in social media. Computers in Human Behavior 97: 202–215. DOI: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.03.032

Rid T (2020) Active Measures: The Secret History of Disinformation and Political Warfare. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

The ‘stay at home’ discourse

For those who can read French, here is an article by Gil Viry and Eva Nada on the lockdown published in the Swiss newspaper Le Courrier on the 5th of May 2020. They argue that the ‘stay at home’ discourse chimes with a romanticised model of the family based on the nuclear home. Yet, many people among the most vulnerable groups cannot stay safely and healthy in their homes: essential workers in precarious jobs, homeless people, women and children experiencing domestic violence, older people living alone, post-divorce families, etc. By favouring a lifestyle over others, this discourse can therefore stigmatise other cultures and lifestyles. https://lecourrier.ch/2020/05/05/un-discours-universel-stigmatisant/

This works well in Google Translate if your French is non existent like mine.

Plagues, monuments and folds in the land

Angus Bancroft

In pandemic times social time seems to give way to virus time. The time the infection takes to replicate, transmit and reinfect is now the basic unit of time which supersedes other rhythms of social and economic life. There is a much longer historical virus time. To be human is to carry the imprint of virus responses in our immune systems and DNA. Viruses have their own biological historical record. Edinburgh is scattered with monuments to the medical history of the place. There are statues to medical pioneers, far too many plaques to read and grasp, each marking the struggle between humanity and mortality. On Princes Street sits a statue to James Young Simpson, one of the pioneers who developed chloroform as an anaesthetic. Another imprint of disease and public medicine is less pronounced but more chatty, the folds in the land . There are the plague mounds, cemeteries, and the plague barriers, remnants of barriers between folk designed to ensure social and contagion distance, and the draughty working class housing that was an attempt to get a grip on miasma and contagion.

The collision between theories of humanity and theories of disease contagion is worth attention. It is written stone and earth. In creates new ways of governing humans, tagging and sorting them and shifting some to the edge of the expanding city, to new sites like Niddrie. Improvement moral, economic, social and sanitary reshaped the city and resorted its inhabitants. Planners theorised how bodies would mix. The vertical social segregation of the Old Town gave way to the horizontal separation of the new suburbs. Internal and external architecture was informed by ideas about hygiene and sanitation alongside privacy, ownership, divisions of domestic labour and time.

The evidence of past social innovations and public health crises is visible in the physical form of the city and also its social dynamics and the cultural and imaginary distance between places. The current pandemic will produce its own legacy in the physical and organisational infrastructure while as a society we move onto the next worry. Looking at past pandemics is going to be crucial to understanding the challenges involved.