1 Introduction

The first independent impact study of the BSL (Scotland) Act 2015, The impact of the British Sign Language (Scotland) Act 2015 on deaf education was published in November 2021 to contribute to the review of the first Scottish national BSL plan, and to act as a discussion point for parents, teachers, organisations and deaf young people themselves about what changes the Act has so far made in relation to their education. The report made 14 recommendations for key stakeholders involved in the implementation of the Act, including a public debate regarding language acquisition and the binary attitudes (speech or BSL), engagement with families of deaf children and young deaf people, transparency in relation to the funding of third sector organisations, an increase in the availability of BSL courses and an improvement in providing BSL content on websites.

No research however has been conducted exploring the perspectives of stakeholders on the education of deaf children and young people in Wales and this follow-up report intends to go some way to address this imbalance, and interesting comparisons can be drawn between the Welsh and Scottish approaches to BSL as a language.

We know that education has played a key role historically in facilitating and at times enforcing monolingualism and wonder whether education could also be used effectively to promote a minority language such as BSL, especially as schools promote what cultural and linguistic knowledge is generally expected of children. This is what has happened in the case of Welsh and Gaelic. Could BSL also be revived through the school system? The Scottish Curriculum for Excellence and the new Curriculum for Wales suggest that BSL can at least be taught to deaf and hearing children, although they do not give deaf children any rights to learn BSL in school. The Scottish Government’s policy, Language Learning in Scotland: A 1+2 Approach, is aimed at ensuring that every child has the opportunity to learn a modern language (known as L2) from P1 until the end of the broad general education (S3). Additionally, each child is entitled to learn a second modern language (known as L3) from P5 onwards. In Wales, the CfW brings together the teaching of Welsh and modern foreign languages to promote a multilingual approach to language learning in Wales.

The difference between Welsh, Gaelic and BSL, however, is the fact that BSL is considered to have ‘dual category status,’ which means that BSL users are seen as both disabled and a language minority. This undoubtedly clouds the minds of both medical and educational professionals who are involved in the education of deaf children. As BSL is not the language of the home in 94% of cases, parents often know little about the language when they discover their baby is deaf.

2 Aims of the research

The overarching research question was:

How does the approach of the devolved administrations of Scotland and Wales to language planning support the promotion and encouragement of BSL in deaf education?

This was broken down into sub-questions as follows:

- What approach(es) do Scotland and Wales take to language planning generally?

- How do Scotland and Wales deliver their devolved powers in relation to education, and to deaf education in particular?

- What bilingual potential exists in both nations in relation to BSL?

- How do Scotland and Wales conceptualise BSL in terms of deaf-disabled and language-minority rights?

- To what extent does the deaf-disabled paradigm persist in Scotland and Wales in the context of deaf education?

- How do stakeholders perceive the role of the national bodies, local authorities, parents, colleges, universities, parents of deaf children and the voluntary sector in relation to deaf children’s use of BSL and bilingual potential?

3 Methods

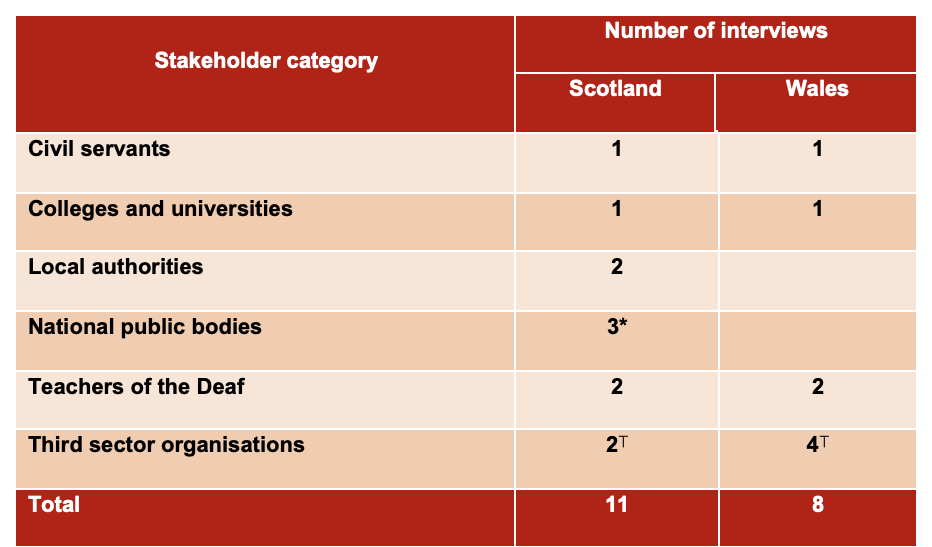

19 interviews with a total of 21 participants were carried out with Scottish and Welsh Government civil servants, national public body representatives, council officials, college and university representatives, families of deaf children, young deaf people, Teachers of the Deaf and third sector employees (see Figure 1).

* One of these interviews had two individuals representing one national public body

⟙ One of these interviews involved three representatives in one organisation covering Scotland and Wales between them

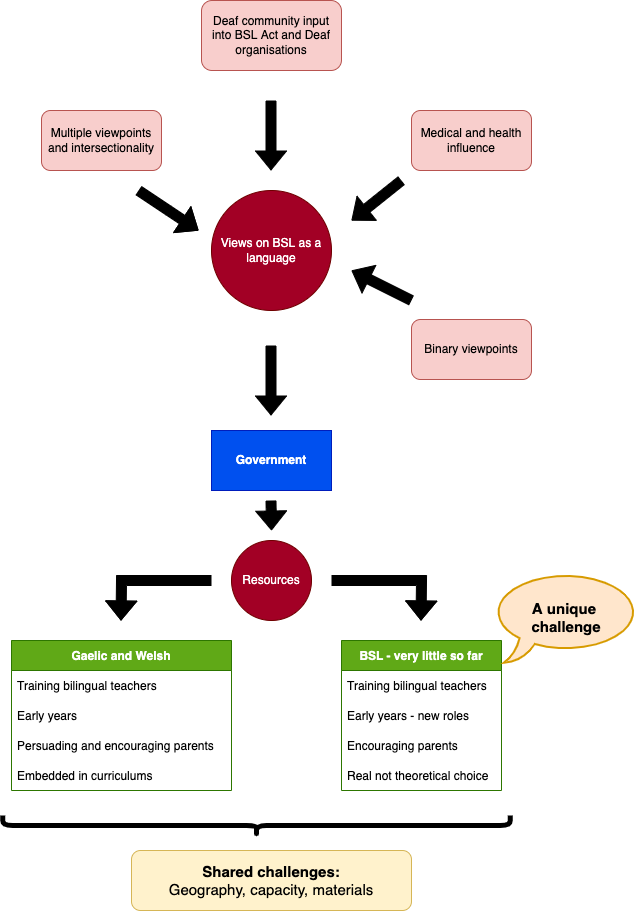

Through the analysis of the interview data, we constructed three over-arching themes which helped us to understand the situation of BSL and deaf children in the education system in Wales and Scotland:

- the varying conceptualisations of BSL as a language;

- the gaps in provision in the crucial early years for deaf children; and

- the lack of resources to move BSL and English bilingualism forward for deaf children in the two countries.

We also found evidence of themes that were identified during the first phrase of this research project: bi/multilingualism, language policy, language attitudes and the BSL (Scotland) Act 2015.

4 Interview findings

The interview findings are summarised in diagrammatic format at Figure 2.

The conceptualisation of BSL as a language was clearly dependent on who was interviewed and rested on whether BSL was viewed as a language or as a communication tool for deaf people. A mixture of deaf and hearing individuals were interviewed, and differing views could be discerned between them, as was the case between top-level and mid- to bottom-level personnel. The conceptualisation of BSL as a language was clear at top-level, that is, government civil servants and national public bodies, and tended to veer towards BSL as a communication tool from mid-level (local authorities) and low-level (ToDS). Similarly, there was a greater awareness of language policy and the right to language, that is, the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child, at top-level, which decreased towards the lower levels, and a greater awareness of language policy among third sector representatives. Nevertheless, at the mid- and low-level, there was generally a positive attitude towards BSL, but this was accompanied by ‘trepidation’ and anxiety in ToDs, and lack of awareness in local authorities about the amount of time it takes to learn a language. It was clear, overall, that those at mid- to low-level tended to frame deaf children according to their audiological status, and that even though health – more specifically audiology – is outside education, it clearly exerts a huge force over the work of ToDs which would explain their attitudes towards BSL.

Gaps in early years provision for deaf children also emerged as an important theme, with recognition that it is this period that is vital for language acquisition. It was clear that the Welsh third sector playgroup representatives understood the importance of language acquisition in the early years, and one of them was quite easily able to apply this to the case of deaf children and BSL. Among ToDs, it was clear that they did not have any proposals to ensure language acquisition in deaf children between the age of zero and three before they start their formal education. The work of Mudiad Meithrin, particularly its Cymraeg i Blant scheme, serves as a useful model for encouraging parents to consider early years learning and childcare for their children in bilingual settings. The link between early years and health services was also made clear, with the role of health visitors in particular highlighted in terms of passing on their personal opinions to parents regarding language choices for their child.

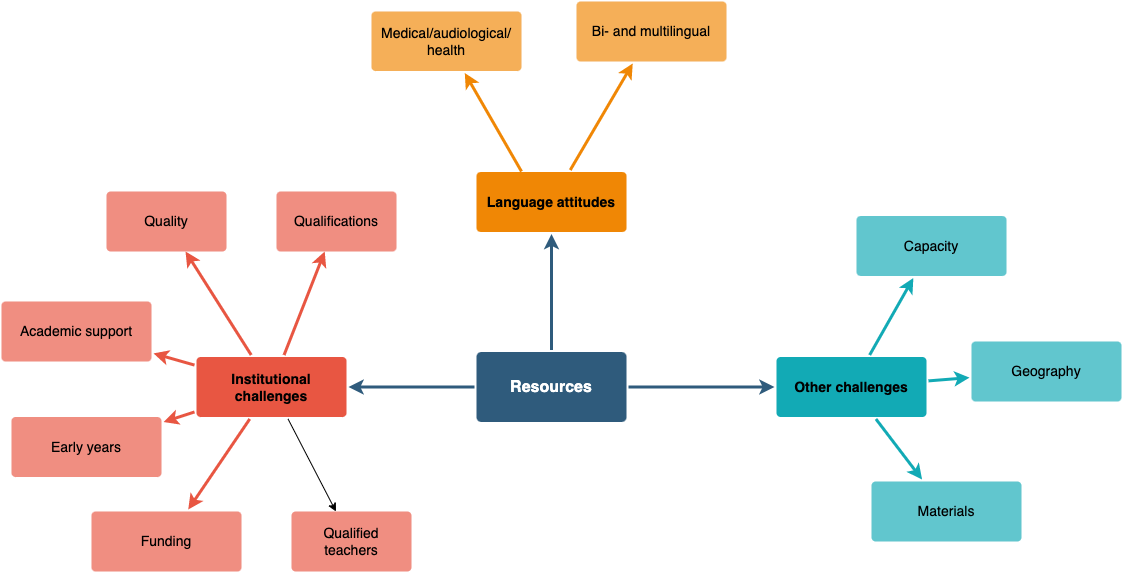

The final theme identified through the interview stage was the availability or scarcity of resources in both Wales and Scotland for the teaching of BSL and in deaf education. These issues are summarised in Figure 3.

There is a clear case for putting BSL learning for the families of deaf children on a formal footing. There is a distinct lack of qualified and/or trained teachers to teach BSL in both Wales and Scotland, compounded by the lack of BSL courses and tailored courses that allow children to learn BSL in the context of the CfE or CfW. Much can be learnt from the capacity-building efforts for Gaelic and Welsh in this regard, and there were examples of language learning in schools by way of partnership working with other schools, local authorities and universities and the utilisation of ‘area teachers.’ It was made clear that it is not known how many BSL teachers there are in the UK, which makes workforce planning all the more difficult.

Ideally, deaf people should teach BSL, but as one national public body representative pointed out: there is a capacity issue, and deaf people have non-traditional academic backgrounds and experience which makes it difficult for them to obtain teaching qualifications and meet standards. There was also some discussion about a ‘centre for excellence’ for BSL.

The ToDs who were interviewed were clear that they were not suitable personnel to teach BSL, although it would be expected that they teach deaf children bilingually. This means that an upskilling of the ToD profession is needed, as well as an uptake in training and recruitment.

Teaching materials also need to be developed tailored towards the Scottish and Welsh curriculums and appropriate for deaf or hearing children rather than adults. A clear case was made for a BSL GCSE (or National 5 in Scotland) which one participant thought would trigger more funding and resources to teach BSL to all year groups in schools.

In terms of early years provision, in Wales, leaders and workers are required to have minimum qualifications, within which framework the requirement to learn BSL could be incorporated.

Finally, funding needs to be put in place to achieve all of the above. To date there appears to have been no concerted effort to allocate funding by either the Welsh or Scottish Governments purely focused on BSL, although both governments already have mechanisms in place for Welsh and Gaelic, which could easily be extended to cover BSL. This could be the way forward to ensure that the capacity is developed for BSL to be provided in early years, primary and secondary education, and for the upskilling of ToDs.

5 Recommendations

Having conducted a review of the impact of the National Plan on deaf education, in particular its issues, failures and successes, in Phase 1 of this project which produced 14 recommendations, we would like to add the following recommendations, grouped under five themes.

Early years

- Utilising Mudiad Meithrin’s Cymraeg i Blant’s model, the benefits of BSL and language pedagogies for deaf children should be incorporated into the training of midwives, health visitors, newborn hearing screening, ear, nose and throat consultants, cochlear implant centre personnel and audiology departments in Wales and Scotland.

- A new profession of BSL Therapists should be developed to support young deaf children and late diagnosed children and those who have not thrived using speech-only methods.

- Funding should be made available for early years workers working in early years learning and childcare settings to learn fluent BSL (to SCQF 6 or Signature/iBSL Level 3).

- Funding and provision should be made to allow parents and families of deaf children to access BSL learning.

Language pedagogies

- We recommend that higher education institutions in Scotland and Wales form a working group to explore the development of language pedagogies courses with pathways in Welsh, Gaelic and BSL, applying a joined-up approach to deal with the common issues associated with bilingual education and the teaching of international languages and 1+2 languages.

BSL Teachers

- The Welsh and Scottish Governments should commission a mapping exercise to establish the number of BSL teachers currently practising in Wales and Scotland so as to ascertain the extent of the qualifications and skills gap for the teaching of BSL.

- There should be an expansion of undergraduate and postgraduate language courses to provide individuals with opportunities to develop fluency in BSL, initial teacher training courses that incorporate BSL as a subject and continuing professional development training courses for teachers who are already qualified, and resources developed to supplement such training courses.

- Until similar provision is established in Wales, the Welsh Government should fund places for four students per year to complete a Primary Education with BSL at the University of Edinburgh.

- Funding should be extended by the Welsh and Scottish Governments to include language sabbaticals for qualified teachers to learn BSL.

- In order to achieve more joined up thinking and action, existing networks for BSL Teachers, deaf teachers and ToDs should work together. These networks include the Scottish Deaf Teachers Group, the British Association of Teachers of the Deaf, d/Deaf Teachers of the Deaf, the Association of BSL Teachers and Assessors, the Sign Bilingual Consortium and the Scottish Sensory Centre.

- Welsh, Gaelic and BSL language provision networks should be afforded the opportunity to work together to deal with the issues common in Welsh-, Gaelic- and BSL-medium education.

Teachers of the Deaf

- The Welsh Government should work in partnership with a ToD qualification provider to provide more opportunities for (language) teachers in Wales to qualify as ToDs with a view to developing a ToD course in Wales.

- Funding should be extended by the Welsh and Scottish Governments to include language sabbaticals for ToDs to learn BSL.

Language policy

- We would urge the Scottish Government to incorporate these recommendations and the recommendations set out in the Phase 1 report in the second Scottish National BSL Plan for the period 2024 to 2030.

6 Next steps

It is clear that there is much to do to improve deaf education in Scotland and Wales, and to increase capacity for BSL learning across the board. More joined up thinking across the sector is essential, and we propose that a UK-wide deaf education conference is organised for 2023 or 2024 to which stakeholders at all levels should be invited to disseminate knowledge, language pedagogies and best practice.

Further research is also needed about how deaf children’s access to the curriculum is affected by being educated through a language in which they are not yet fully fluent, to further support the inclusion of BSL in deaf children’s education.

Rob Wilks, Cardiff University

Rachel O’Neill, University of Edinburgh

10 October 2022