Does the ACEs framework traumatise and stigmatise those it should support?

David Ford is the Founder and Head of Expert Link, a national organisation with a network of people around the country, predominately with lived experience of multiple disadvantages.

This blog was originally posted on 19th August 2019 at: http://expertlink.org.uk/blog/aces-framework-traumatise-stigmatise-support/

For years, Expert Link has called for greater recognition of the link between multiple disadvantages (namely experience of three of more factors such as homelessness, mental health difficulties, substance misuse, contact with the criminal justice system and domestic abuse) and adverse childhood experiences. In 2015, I was part of the research team that worked on the Hard Edges report, speaking with many people across England who, like me, had lived experience of multiple disadvantage. Through listening to peoples voices we found that all had experienced poverty, as well as a range of social and family factors. Crucially, we found that nearly 9 in 10 of us had experienced some form of adverse childhood experience.[1]

At Expert Link we are clear that an increased understanding of the role adverse childhood experiences can have on individuals is crucial if society wants to respond effectively to issues such as the increasing number of people currently rough sleeping and the high numbers of people dying on the streets. However, a current focus on an Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE’s) test or framework, has made us concerned about the potential affect this may have on our community.

What is the ACEs framework?

The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE’s) test or framework is based on a study conducted in the USA in the late ‘90s.[2] The study looked at ‘the relationship of health risk behaviour and disease in adulthood to the breadth of exposure to childhood emotional, physical, or sexual abuse, and household dysfunction during childhood.’ Participants in the study were 75% white, middle class ,with good education, in good employment, with health insurance and born between 1938 – 1940.

The framework itself, which is being advocated in some quarters to be applied universally to all children in the UK, scores people, rather crudely, on the number of adverse childhood experiences they have experienced before they were 18. The set list of ACEs include parental mental and physical abuse, sexual abuse and rape, neglect, and ‘having family members experience mental health problems, addiction or incarceration.’ Not only are the questions used subjective, but there are only 10 being used from a much larger set of questions used in the original study.

My experience

As someone who has experienced multiple disadvantages, adverse childhood experiences and works to use my experiences to make positive social change, I decided to search the internet and take the test. I scored 6.

Looking at the research, this means that the risk of me making a suicide attempt is more than 30 times higher than someone with an ACE score of zero. My life expectancy is also 20 years younger than those with none, and as a 52 year old man, this was a worry! But it was more than a worry. I didn’t sleep. I suffer from mental illness and my depression took over. I struggled to get out of bed, consumed with the thought that in reality I was 72 with only a couple of years left to live. At about the same time a good friend of mine who was the same age as myself and with a similar childhood passed away. I was not in a good place, but fortunately I have great support network around me and I pulled through.

Many people who have experienced multiple disadvantages, who are very likely to have experienced adverse childhood experiences, are also likely to be isolated. My immediate worry is that many will complete the test, see the implications for life expectancy, and be left anxious and afraid, choosing not to engage with support agencies. Worse still they may decide to take their own lives. Amazing people with skills and talents could lose all hope in their recovery.

It is not true that a high score will lead to negative outcomes

It is critical that people understand that getting a high score on the test does not equate to dying 20 years younger or some of the other negative health outcomes will happen. The Science and Technology Committee final report into ‘Evidence-based early year’s intervention,’[3] is clear to note that although there is correlation, experiencing these problems is not guaranteed. Many people who experience adverse childhood experiences do not have negative health outcomes later in life, and many people who have negative health experiences later in life have not experienced adverse childhood experiences.

But does everyone know this? Is the necessary work being done by advocates of the ACE framework to ensure that people who have experienced adverse childhood experiences are adequately informed and supported – in particular those who are not connected with current services?

The risk of stigmatising

Another key concern relates to the stigmatising effect the adoption of this framework could have on parents who have experienced multiple disadvantages. The experiences considered within the framework are limited to family behaviours – violence in the family is included, whereas violence outside is not. Experiences of poverty, insecure housing and homelessness are also not included. The negative outcomes are linked almost solely to the parent, with little or no reference to economic or political factors like changes to the welfare system, limited provision of mental health support and the shortage of decent, habitable, housing.

Such a framework therefore risks stigmatizing parents who have experienced multiple disadvantages, parents who themselves have likely experienced adverse childhood experiences. This stigmatizing will not only increase feelings of guilt, shame and anxiety for individuals, but also risks isolating us from participating in decision making. An approach which has the potential to see behind behaviors has itself failed to see behind the reasons for parental actions.

Listen, hear, empower

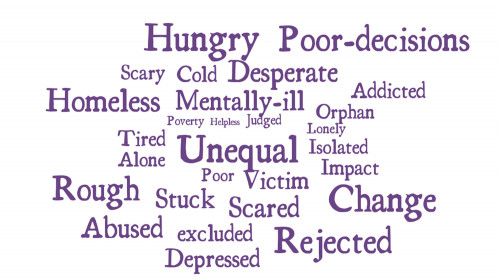

It is important that people are made aware of the consequences that adopting crude frameworks in response to complex issues can have on individuals. As a society our response to supporting people who are having difficult times should not be to promote fatalistic stories, but to listen and hear their individuals skills and talents, expertise and wishes. Instead of labelling and stigmatising people, we need to empower people and reflect on how we can work together.

In the rush to prevent negative experiences, we must not forget about those of us who have already lived them.

To Jose

[1] https://lankellychase.org.uk/resources/publications/hard-edges/

[2] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9635069

[3] https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmsctech/506/506.pdf

(Expert Link)

(Expert Link)

Recent comments