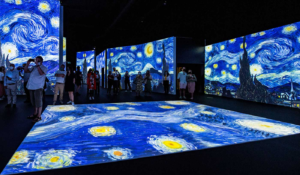

Van Gogh Alive – the touring exhibition of Vincent Van Gogh’s famous paintings – has recently arrived in Edinburgh. What sets the exhibition apart from others is that, instead of displaying the artist’s work framed and on a wall, Van Gogh Alive projects them onto huge screens.

The idea is to make it feel as though the visitor is walking among Van Gogh’s paintings. In fact, Van Gogh Alive labels itself as a ‘multi-sensory experience’ rather than an ‘ordinary art exhibition’. Although the paintings are projected onto a flat screen – much like a wall in an art gallery – they are not static. The projections move and some aspects of the paintings are animated. This movement is set to music, not unlike a film soundtrack. Though the experience contains many sensory elements – the gallery is infused with scents and aspects of specific paintings are constructed so that visitors can walk through them – the projections and matching music dominate.

If you forget the scents and the sets, Van Gogh Alive would be distinctly cinematic. The experience of sharing a dark room with strangers in order to watch moving pictures set to music is inherently cinematic. Therein lies the problem.

It may be interesting and novel to incorporate the other senses – hearing, scent and touch – but sight is still what defines our experience of art. Van Gogh Alive is an incredibly accessible exhibition with BSL and narrated videos to accompany any reading panels so that visitors with hearing or sight difficulties can also enjoy the experience. Still, the exhibition unavoidably privileges sight. Cinema, sculpture and art might be motivated by the desire to make the viewer feel but they are largely dependent on sight as a way to elicit this feeling. It seems that the experience of art – even when it tries not to be – is inherently about looking.

Written for The Film Dispatch by Niamh Carey-Furness.