The second-order structure function corrected for systematic error.

In last week’s post, we discussed the corrections to the third-order structure function ![]() arising from forcing and viscous effects, as established by McComb et al [1]. This week we return to that reference in order to consider the effect of systematic error on the second-order structure function,

arising from forcing and viscous effects, as established by McComb et al [1]. This week we return to that reference in order to consider the effect of systematic error on the second-order structure function, ![]() . We begin with some general definitions.

. We begin with some general definitions.

The longitudinal structure function of order ![]() is defined by:

is defined by:

(1) ![]()

where ![]() is the longitudinal velocity difference over a distance

is the longitudinal velocity difference over a distance ![]() . From purely dimensional arguments we may write:

. From purely dimensional arguments we may write:

(2) ![]()

where the ![]() are dimensionless constants.

are dimensionless constants.

However, as is well known, measured values imply ![]() where the exponents

where the exponents ![]() are not equal to the dimensional result, with the one exception:

are not equal to the dimensional result, with the one exception: ![]() . In fact it is found that

. In fact it is found that ![]() is nonzero and increases with order

is nonzero and increases with order ![]() .

.

It is worth pausing to consider a question. Does this imply that the measurements give ![]() ? No, it doesn’t. Not only would this give the wrong dimensions but, more importantly, the time dimension is controlled entirely by the dissipation rate. Accordingly, we must have:

? No, it doesn’t. Not only would this give the wrong dimensions but, more importantly, the time dimension is controlled entirely by the dissipation rate. Accordingly, we must have: ![]() , where

, where ![]() is some length scale. Unfortunately for aficionados of intermittency corrections (aka anomalous exponents), the only candidate for this is the size of the system (e.g.

is some length scale. Unfortunately for aficionados of intermittency corrections (aka anomalous exponents), the only candidate for this is the size of the system (e.g. ![]() ), which leads to unphysical results.

), which leads to unphysical results.

Returning to our main theme, the obvious way of measuring the exponent ![]() is to make a log-log plot of

is to make a log-log plot of ![]() against

against ![]() , and determine the local slope:

, and determine the local slope:

(3) ![]()

Then the presence of a plateau would indicate a constant exponent and hence a scaling region. In practice, however, this method has problems. Indeed workers in the field argue that a Taylor-Reynolds number of greater than ![]() is needed for this to work, and of course this is a very high Reynolds number.

is needed for this to work, and of course this is a very high Reynolds number.

A popular way of overcoming this difficulty is the method of extended scale-similarity (or ESS), which relies on the fact that ![]() scales with

scales with ![]() in the inertial range, indicating that one might replace

in the inertial range, indicating that one might replace ![]() by

by ![]() as the independent variable, thus:

as the independent variable, thus:

(4) ![]()

In order to overcome problems with odd-order structural functions, this technique was extended by using the modulus of the velocity difference, to introduce generalized structure functions ![]() , such that:

, such that:

(5) ![]()

Then, by analogy with the ordinary structure functions, taking ![]() with

with ![]() leads to

leads to

(6) ![]()

This technique results in scaling behaviour extending well into the dissipation range which allows exponents to be more easily extracted from the data. Of course, this is in itself an artefact, and this fact should be borne in mind.

There is an alternative to ESS and that is the pseudospectral method, in which the ![]() are obtained from their corresponding spectra by Fourier transformation. This has been used by some workers in the field, and in [1] McComb et al followed their example (see [1] for details) and presented a comparison between this method and ESS. They also applied a standard method for reducing systematic errors to evaluate the exponent of the second-order structure function. This involved considering the ratio

are obtained from their corresponding spectra by Fourier transformation. This has been used by some workers in the field, and in [1] McComb et al followed their example (see [1] for details) and presented a comparison between this method and ESS. They also applied a standard method for reducing systematic errors to evaluate the exponent of the second-order structure function. This involved considering the ratio ![]() . In this procedure, an exponent

. In this procedure, an exponent ![]() was defined by

was defined by

(7) ![]()

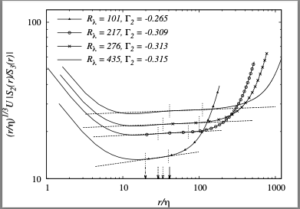

Results were obtained only for the case ![]() and figures 9 and 10 from [1] are of interest, and are reproduced here. The first of these is the plot of the compensated ratio

and figures 9 and 10 from [1] are of interest, and are reproduced here. The first of these is the plot of the compensated ratio ![]() against

against ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the dissipation length scale and

is the dissipation length scale and ![]() is the rms velocity. This illustrates the way in which the exponents were obtained.

is the rms velocity. This illustrates the way in which the exponents were obtained.

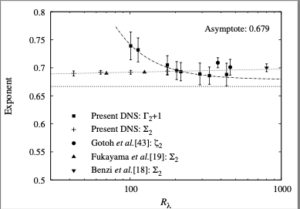

![]() with Reynolds number, compared with the variation of the ESS exponent

with Reynolds number, compared with the variation of the ESS exponent ![]() . It can be seen that the first of these tends towards the K41 value of

. It can be seen that the first of these tends towards the K41 value of ![]() , while the ESS value moves away from the K41 result as the Reynolds number increases.

, while the ESS value moves away from the K41 result as the Reynolds number increases.

![]() , hence

, hence ![]() , which is why we plot that quantity. We may note that figures 1 and 2 point clearly to the existence of finite Reynolds number corrections as the cause of the deviation from K41 values. Further details and discussion can be found in reference [1].

, which is why we plot that quantity. We may note that figures 1 and 2 point clearly to the existence of finite Reynolds number corrections as the cause of the deviation from K41 values. Further details and discussion can be found in reference [1].

[1] W. D. McComb, S. R. Yoffe, M. F. Linkmann, and A. Berera. Spectral analysis of structure functions and their scaling exponents in forced isotropic turbulence. Phys. Rev. E, 90:053010, 2014.