The reproduction of lichens

This is the audio (below) for this halt. The text below is a transcription of the audio! The audios do not contain all the content written in the text to keep the audios engaging. If you want to have more details, check out the text. Enjoy!

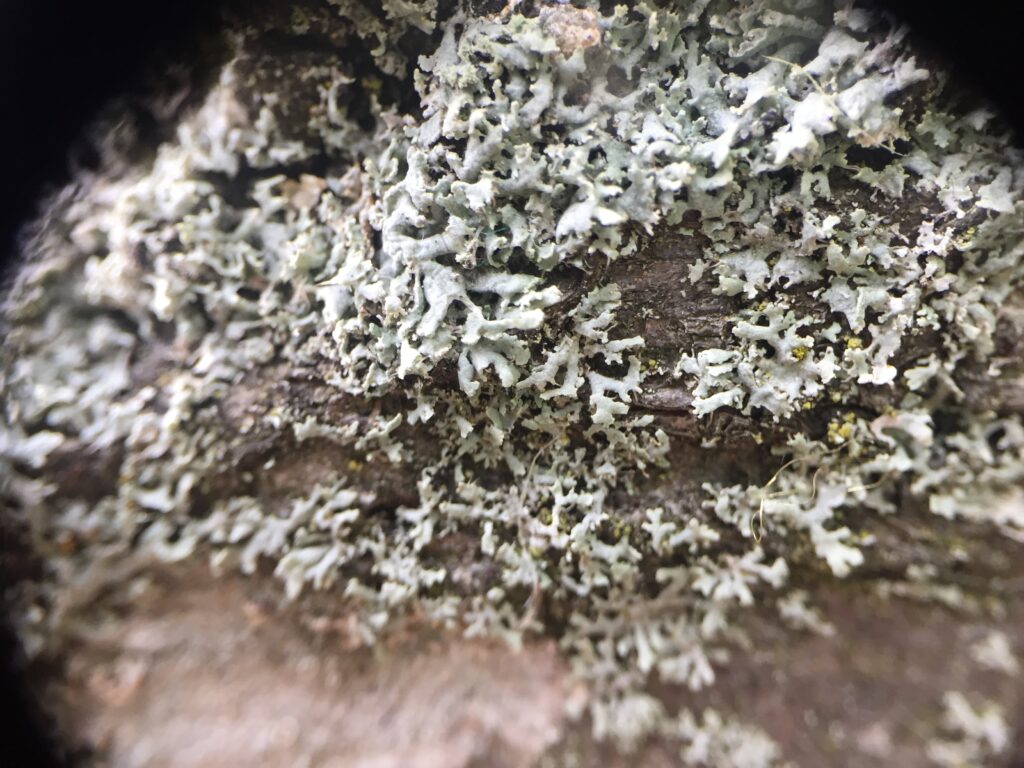

Have you found the tree we are going to observe? Here are some pictures to help you find it.

How do lichens disperse and reproduce?

Like fungi, lichens have quite complex and diverse reproductive strategies. The strategies that the lichens use depend on the environmental conditions.

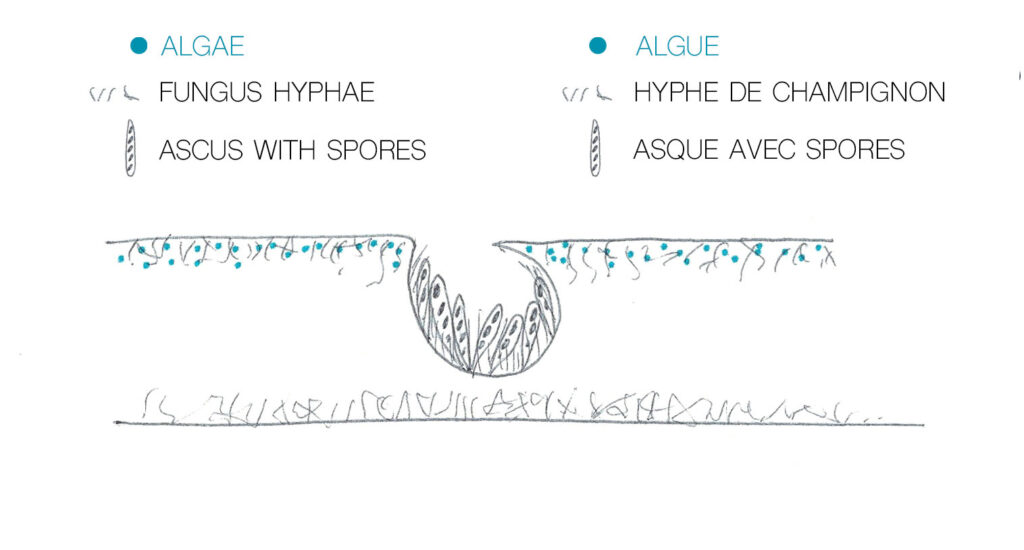

To begin with, only the fungal partner can reproduce sexually. The photobiont (the photosynthetic partner) and the mycobiont (the fungal partner) together can reproduce asexually.

But what is the difference between sexual and asexual reproduction?

Asexual reproduction means that the offspring is created by only one parent without the fertilisation and the production of reproductive cells – called the gametes.

In sexual reproduction, offsprings are produced by two partners of different sexes. These partners produce gametes that are morphologically and genetically different. The union of these gametes produces a zygote that will become the offspring.

- ASEXUAL REPRODUCTION IN LICHENS

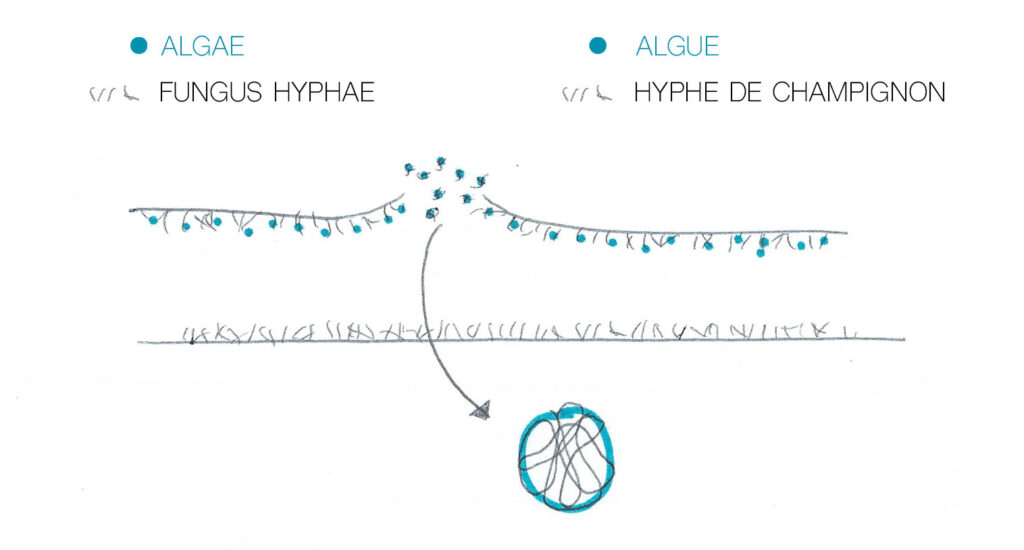

This is done by fragmentation, by the breakage of specialised cells called soredia and isidia, which are dispersed by the force of the wind or the trampling of animals. For example, when a bird walks on the branches of a tree and fly to another tree, it may disperse the isidia on this other tree. Isidia and soredia are two different strategies of the lichens to reproduce asexually.

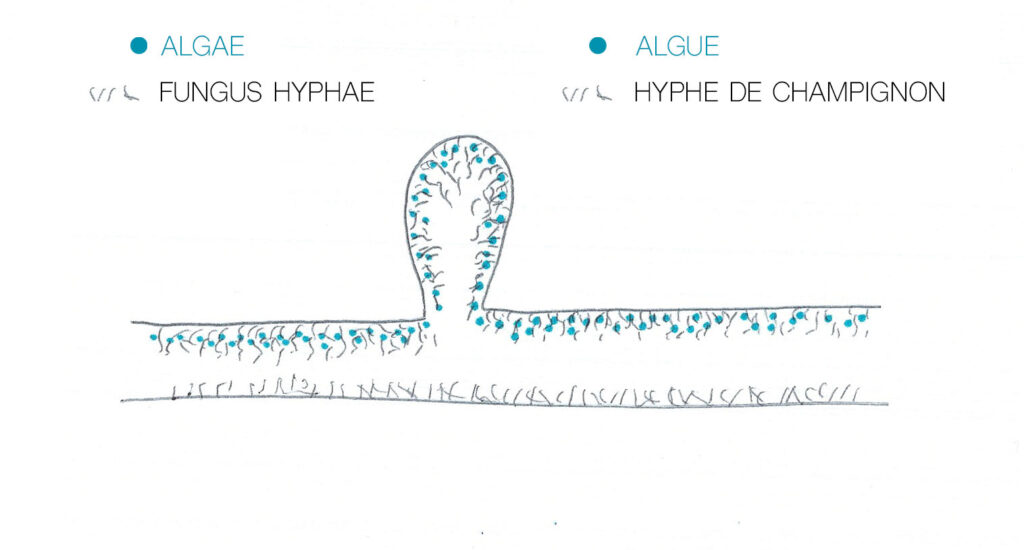

Isidia are small structures formed on the surface of the thallus that can detach from it. Both partners (fungus and algae) are present inside the isidia (see diagram). The forms of this structure are varied and constitute an important element in taxonomy. The second picture in the slideshow is a picture of the isidia of

Soredia, (soradium in singular) produced by soralia (soralium in singular), are small mealy or granular masses consisting of small clusters comprising an algal cell surrounded by fungal hyphae. These soralia are created as a result of interruptions in the cortex (the upper surface of the lichen thallus). Soralia can be diffuse and found all over the thallus or they can be well delimited. They are liminal when they develop on the thallus, marginal when they are formed at the margin of the thallus and terminal when they are located at the end of the lobes.

Finally, the mycobiont (the fungus) can produce spores that are not involved in the sexual process. These spores are called conidia (or pycnospores). They are produced at the end of hyphae and vary in shape and size. The organs that contain them are called pycnidia. The pycnidia containing the conidia are dispersed without the photobiont and therefore must find an algal partner in order to reconstitute a lichenised thallus.

2. SEXUAL REPRODUCTION IN LICHENS

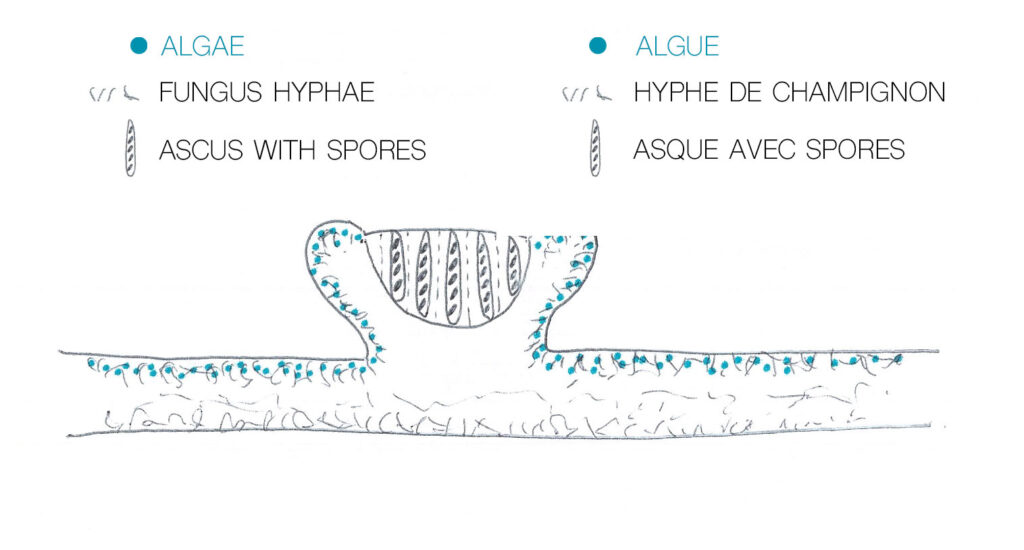

There are two main forms of sexual reproduction: apothecia and perithecia. These forms produce spores in asci (plural, ascus in singular) (see diagram). When the spores are dispersed, they must find an algal partner in order to form a lichen.

How does the fungus overcome the problem of finding a photosynthetic partner (alga or cyanobacteria) to “lichenise” ?

Different species of lichen will find different strategies to overcome this problem. Some species will have their spores (of the fungus partner) agglutinated with some cells of the alga or cyanobacteria so as to have a better chance of developing. Others may survive by forming a symbiosis with other algae (which are not normally their partners) or may insert their hyphae into a neighbouring lichen to steal some of its algae (see Science Infuse file, only accessible in French).

Note: Today, one in five of all known fungi species can form a lichen. Some fungi formed lichens earlier in their evolution but have lost this ability. Other fungi have had different photosynthetic partners during their evolution. Finally, some fungus species can choose to live in symbiosis with algae or live independently (Sheldrake, 2020).

The apothecia are cups that can be concave, convex or flat (depending on the species). There are two types of apothecia, those called lecanorine which contain a layer of cells of the photobiont – the algae or cyanobacteria – and lecidine which do not.

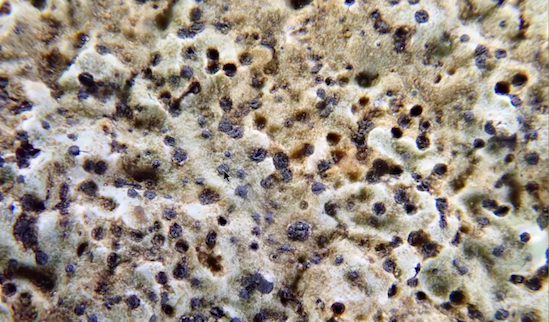

Perithecia are small wombs embedded in the thallus. Contact with the outside environment is through a small punctiform cover at the top of the perithecia called an ostiole. The lichen in the slide show below is Bagliettoa calciseda (photo shared at the British Lichen Society meeting).

The process by which the genes of the algal partner and the fungus are combined is still poorly understood despite the fact that we know the structures well.

Hopefully, this introduction will help you identify lichens as the reproductive apparatus is an important criterion. In the next step, we will discuss identification and these steps.

Identification activity

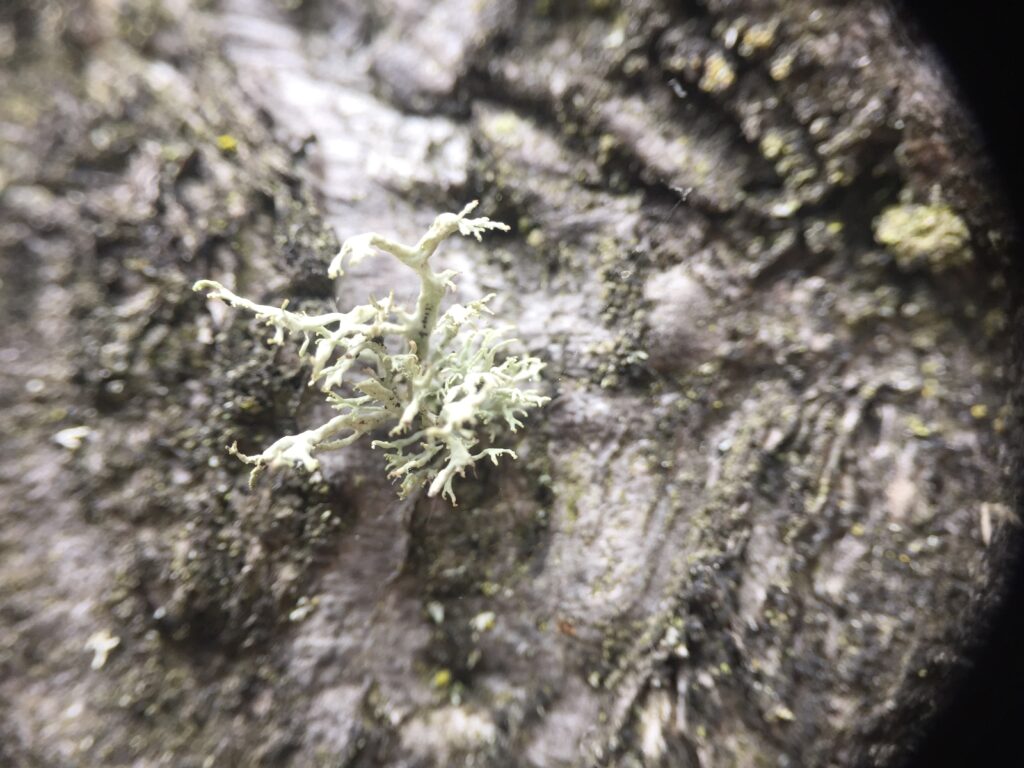

We will introduce new species: Candelariella reflexa, Lepraria, Hypogymnia physodes, a specimen from the genus Melanohalea and Evernia prunastri. Some specimens of the genus Physcia are also present. Can you spot them?

Candelariella reflexa is a crustose lichen. The crustose thallus is formed of yellow to yellow-green granules. This lichen is very similar to Candelaria concolor (do you remember the small yellow lichen with small lobes?) and can only be differentiated if you look closer to it. Candelaria concolor has small folioles (and can be more categorised as a foliose lichen) compared to Candelariella reflexa which is a crustose lichen.

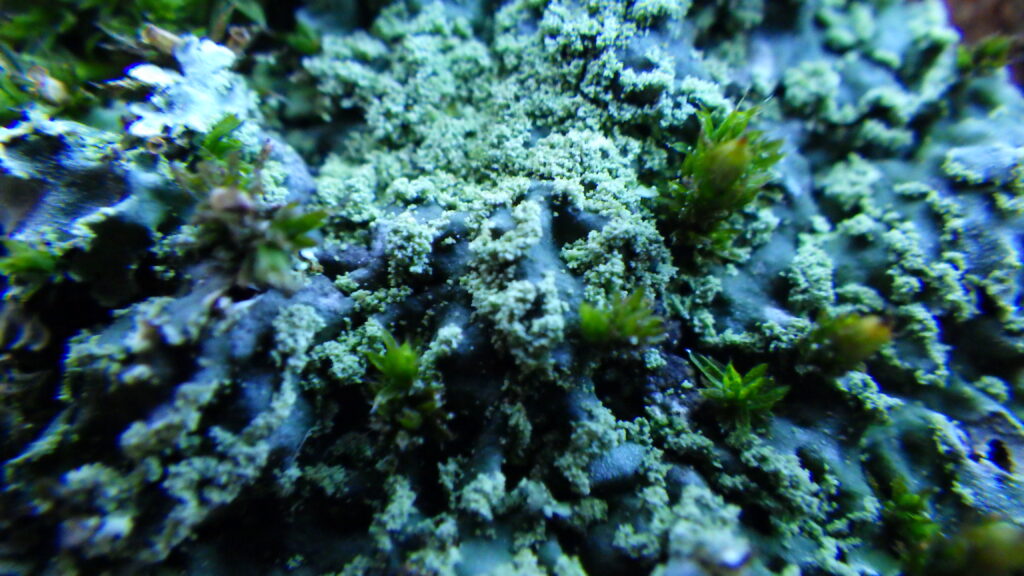

We have talked about the genus Lepraria. The species are difficult to tell apart so we will leave that and already identify the main genus. If you want more information on the species of the genus Lepraria, you can check out the identification key here and more information on how to use an identification key here. On the second picture below, you can see the powdery granules (soredia) which are the reproductive apparatuses of the lichen.

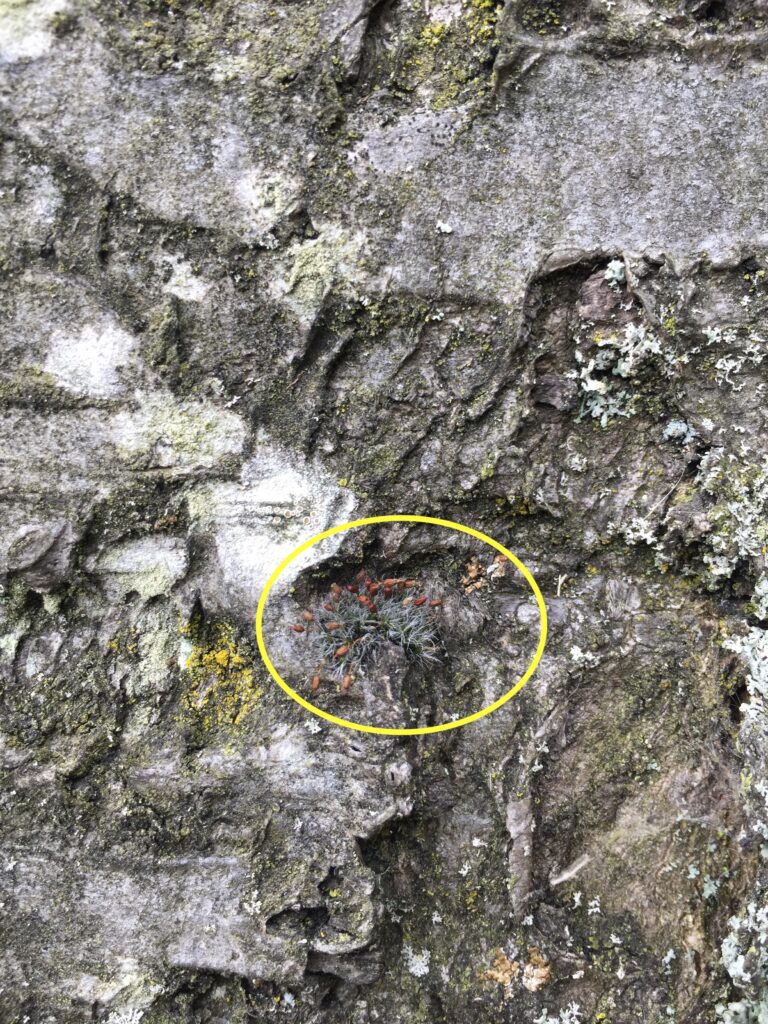

At the time I did the lichen identification, I could also see the sporophytes of the moss (the reproductive apparatuses of the mosses). Can you still spot some mosses?

We have briefly talked about Hypogymnia physodes but I will introduce this specimen a bit more just now.

Hypogymia physodes is a foliose lichen and has a shiny grey-green with narrow swollen and hollow lobes. The under-surface of the lichen is light brown at the margin and dark brown to black in the centre. The lobe ends are turned up and have soredia on the underside. This genus is known to not have any rhizine and is thus attached directly to the substrate by patches of fungal hyphae. This species is common on trees, mosses, and rocks and in places polluted with SO2 (sulphur dioxide).

Evernia prunastri. This species is often confused with fruticose lichens as it is attached at one point, however, the distribution of the algal layer makes it belong to the group of foliose lichens. The thallus is strap-shaped and is yellow to green grey on the upper cortex. The lower part of the thallus is much paler with white patches due to the lack of algal layer underneath.

Lastly, I want to show you the spark of colour when a fungus attacks a lichen. This type of fungus is called a lichenicolous fungus. On the picture, these are the small orange dots on the powdery Lepraria spp.

References

For more detailed information on lichens, as well as to have access to a determination key, I recommend you check the references (only accessible in French):

Sérusiaux, E., Diederich, P., & Lambinon, J. (2004). The macrolichens of Belgium, Luxembourg and northern France. Keys to identification.

All diagrams were created by the author and are under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license.

Feedback

If you don’t continue the ride, can you give us feedback on your experience here ? It will help us improve!

Let’s meet at the Dalry cemetery…. Some spooky discoveries await! As always, more details on the location on the map 👇🏽👇🏽