Lichens and medicine

This is the audio (below) for this halt. The text below is a transcription of the audio! The audios do not contain all the content written in the text to keep the audios engaging. If you want to have more details, check out the text. Enjoy!

Have you found the tree we will be looking at? It is the one highlighted by the red arrow on the picture below.

A little bit of history….

The evolution of the lichen symbiosis is interesting because the co-evolution of the alga and the fungus has taken place several times at different periods and for different species. Lichens represent a success story of several million years. Fossils of lichens have been found and have been dated to approximately 418 million years ago (between 420 and 350 million years ago), in the Devonian period. To give you an idea, humans appeared 200 million years ago, and the big bang happened 13.8 billion years ago.

If you could go back in time to that Devonian era, you wouldn’t see trees or plants – which would exist but would be very small – but Prototaxites. These organisms, sometimes the size of a house, dominated the landscapes in Africa, Australia, Europe, North America and Asia for 40 million years, 20 times the lifetime of humans. These huge organisms were large lichen-like structures created by the symbiosis between algae and fungi. Despite the Prototaxites being very similar to lichens, there is still much debate on what this organism was. The Prototaxites disappeared, probably due to the increased size of shrubs and trees which would have shaded the organisms and prevented them from using sunlight for photosynthesis. Photo and more info on the uncertainty surrounding these organisms here.

Lichens have thus been around for a while and have changed their shapes and forms.

What makes up a lichen?

Lichens are full of chemicals.

To differentiate one species from another, lichenologists – the people who study lichens – apply bleach or caustic soda (among other things) on the thallus which creates a chemical reaction and causes the colour of the lichen thallus to change. Based on this colour, we can distinguish between two lichens that are morphologically similar but structurally different.

This type of test must be carefully done because it kills the lichens. Often the chemicals are applied to a very small part of the thallus and only to a few lichens found on the substrate – the surface on which the lichen is found.

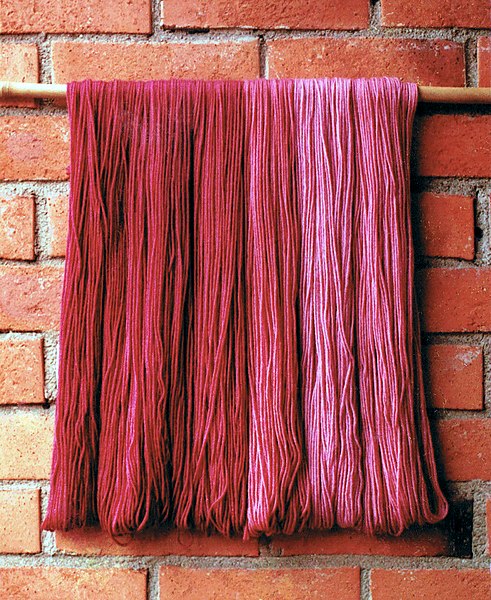

In the past – and still today – lichens were used for dyeing. Lichens are full of chemicals and mixing them with other products, such as ammonia, creates colours which are interesting for colouring materials such as wool. In Scotland, a place where there was and still is a great deal of wool production, certain species of lichen were used extensively for dyeing, first on a small scale and then with commercial purposes. Three-legged cauldrons were often seen in the Scottish islands where lichens were boiled. The last producers of wool and traditional clothing ceased production in 1997.

The photo below shows the different colours that can be obtained by dyeing wool with lichens. The darker colours are obtained by dipping the yarns in the mixture several times.

Despite this, lichens, as we have already said, grow very slowly and their harvest must be done properly, considering the time they need to grow.

Traditional uses of lichens

Lichens have been used and are still used all over the world (Crawford, 2015), especially in traditional medicine. This is due to their second metabolites which are known to be physiologically active and can be used as antibiotics. Other uses of lichens depend on their carbohydrates.

In Europe, the origin of the use of lichens in traditional medicine can be traced back to the 4ᵉ and 3ᵉ century BC, when lichens were recorded by ancient Greeks. The most common uses of lichens in medicine are to treat wounds, skin and digestive problems as well as in obstetrics and gynaecology. The uses depended as much on the country and customs as on the species found in the area. For example, in the 18ᵉ century, the “highlanders” – the inhabitants of the Highlands, in Scotland – mixed the lichen Parmelia saxatilis (pictured below), with tobacco. In Sweden, the same species was used to remove warts and in Bhutan it was used to treat leprosy, uterine bleeding and ulcers in children. Other species such as Evernia prunastri are used to create perfumes. Lichens are also used in pharmacology and cosmetology. Evernia prunastri and Parmelia saxatilis are not rare species and can easily be found – sometimes in cities. Parmelia saxatilis can also produce a red-brown dye.

Can we eat lichens?

Lichens are not digestible by animals, but some species have developed enzymes that allow them to digest the chemical components of lichens.

Reindeer that feed on lichens (the Evernia type) have special enzymes called lichenases to digest lichens and their chemicals. Nevertheless, in some customs, lichens are a source of food. The Salish people (North western USA and Canada) consumed lichens. Mixing them with other food sources captured carbohydrates. For example, lichens of the genus Bryoria were rinsed and soaked in water for several hours before being worked by hand to remove the vulpine acids (lethal to some gastropods). The lichens were then cooked in a covered fire pit (with moss and earth) heated over a fire for several days. When the lichens were dug up, they were gelatinous and black.

In our society, it is very rare to eat lichens, but sometimes there are few other options….

During the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina (1992-95), some lichens of the genus Usnea and Evernia were used in porridges and to create flour (Redzic et al., 2010). Finally, in Japan lichens of the genus Umbelicaria are edible if prepared properly. They have been used as a food source during famines.

Lichens have therefore been part of human life for centuries, whether it is to feed us, to keep the ecosystem functioning or to stimulate thought.

Activity

On this tree we will mostly see crustose lichens that we have already seen. Can you name them?

Naming the organisms we share the world with helps giving value and build companionship.

“Philosophers call this state of isolation and disconnection “species loneliness”—a deep, unnamed sadness stemming from estrangement from the rest of Creation, from the loss of relationship. As our human dominance of the world has grown, we have become more isolated, lonelier when we can no longer call out to our neighbors (the other living beings). It’s no wonder that naming was the first job the Creator gave Nanabozho.”

― Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants

There are some crustose lichens. As a reminder, crustose lichens are lichens that are incrusted in the bark. It is impossible to remove the lichen without the substrate – the surface on which the lichen is found. The powdery green specimens next to this lichen of the genus Lecanora are unicellular algae – they are not part of a lichen. You can also see mosses. It’s quite common to confuse lichens with mosses despite the fact that they are completely different. A moss is a plant, completely photosynthetic. As we said, a lichen is a symbiosis and is more of a fungus than a plant. Indeed, a lichen is composed of 95% fungus and the rest, algae.

On the picture below, you can see the difference between the unicellular alga – the powdery green cells that sticks onto your finger when you press it against the bark, the moss and the lichens.

There is a part of the trunk where there is more mosses and this could be due to the water pouring down the trunk. Mosses thrive in heavily watered environments.

There are some other lichen species that are in minority but if you look for it you will be able to find them.

There are some Physcia spp., a genus that we have already seen.

A new type of lichens that we have not seen yet is Candelaria concolor. This lichen is hard to see with the naked eye. The lemon yellow to green thallus has a size of 0.5 to 2cm and is minutely foliose. The lobules – small lobes – are erect and produce dense clusters on the surface of the thallus ending with soredia on the margins. This species develops in dry well-lit environments.

Lastly, you might spot, Phaeophyscia orbicularis. It has adpressed orbicular thallus of up to 3cm diameter, is very variable as it can be pale brownish grey to brown to black. The lobes are long and can be divided at the tips. This lichen is common on nutrient-enriched (enriched due to pollution) bark, twigs and basic stones. It is especially common in urban areas on concrete and trunks as it very tolerant to NO2 (released by car fuel).

At the next halt, I’ll take you on a dive into the reproduction of lichens and like mushrooms, it’s exciting but not always obvious!

References

– Information on Prototaxites was first found in:

Sheldrake, M. (2020). Entangled life: how fungi make our worlds, change our minds & shape our futures. Random House.

– Crawford, S. D. (2019). Lichens used in traditional medicine. In Lichen secondary metabolites (pp. 31-97). Springer, Cham.

– Redzic, S., Barudanovic, S., & Pilipovic, S. (2010). Wild mushrooms and lichens used as human food for survival in war conditions; Podrinje-Zepa Region (Bosnia and Herzegovina, W. Balkan). Human Ecology Review, 175-187.

Feedback

If you don’t continue the ride, can you give us feedback on your experience here ? It will help us improve!

Let’s meet in Murieston Park ! As always more details on the location on the map 👇🏽👇🏽

Informasi ini bagus