End of the walk

This is the audio (below) for this halt. The text below is a transcription of the audio! The audios do not contain all the content written in the text to keep the audios engaging. If you want to have more details, check out the text. Enjoy!

Welcome to Dalry cemetery!

Credit: Dalry cemetery, picture taken by the author, Lucie Pestiaux (2021). CC BY-SA 4.0.

Credit: Dalry cemetery, picture taken by the author, Lucie Pestiaux (2021). CC BY-SA 4.0.

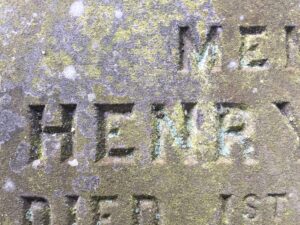

The last time I came, I was astonished by the wilderness of this place. The disorganised orchestra of flowers and plants, of fallen stones and names of dead. I imagined the souls and the ashes of the dead growing into wild plants. I could see life cycling from death to life. I could feel the interconnections between all beings, between the animate – the plants – and the inanimate – the dead buried and the stones. I touched lichens eroding the stones, highlighting the always changing cycles of life. Wilderness is in the interstices of the built environment, where life finds a place to grow and thrive. Learning to observe this life within the cement, this emergence of colour in the grey requires to pay attention to the details and to other more-than-humans. I found peace with the dead, and the bees, with the lichens and the flowers.

This stroll in Dalry Cemetery made me think of the research carried out by Anne Pringle studying the demography of lichens in Petersham Cemetery, Massachusetts. She is looking at the demography of lichens to answer this question: Why do organisms age?

This is especially interesting as  it is thought that the vast majority of mycelial fungi (thus, excluding single-celled organisms such as yeast) are immortal (Osiewacz, 2002). What Anne Pringle (2018) found after a bit less than a decade of long-term research is that what was considered an individual (lichen) does not seem to age and senesce, but some parts might detach. The question thus is not if the lichen ages but what is an individual and what enables organismal behaviours and coherence?

it is thought that the vast majority of mycelial fungi (thus, excluding single-celled organisms such as yeast) are immortal (Osiewacz, 2002). What Anne Pringle (2018) found after a bit less than a decade of long-term research is that what was considered an individual (lichen) does not seem to age and senesce, but some parts might detach. The question thus is not if the lichen ages but what is an individual and what enables organismal behaviours and coherence?

Credit: Lichens transforming the graves, picture taken by the author, Lucie Pestiaux (2021). CC BY-SA 4.0.

Such mysteries show how much is unknown right below our feet. It highlights the connections between all beings. The ashes of a dead human enable the growth of a plant. The stone of the grave became the support on which the lichen grew.

It also shows other ways by which organisms live in the world. Lichens might be immortal, always changing and growing.

We have reached the end of the walk. Thank you for participating and joining until the end of this adventure. Thanks also for having opened your ears and your eyes to discover this peculiar organism and its diversity.

I hope this walk has made you think about the presence and importance of lichens in the urban ecosystem and in our understanding of natural phenomena. You will have noticed that our ideologies influence what we see and what we want to see (like Schwendener who talked about the alga being the “slave” of the fungus – see information at the Leopold Park on symbiosis).

Current discoveries about fungi and other organisms, such as lichens, reveal ways in which beings live on our planet. Perhaps the crises that are coming (social, ecological, and political) will trigger changes in our perception of the world, deconstructing a nature/culture dualism, and rethinking the place of human in a world made of complex networks of interactions.

In any case, I hope this walk is a step towards discovering the city in another way, decolonising urban spaces from anthropocentric ideas and seeing them not as only human spaces, but as complex interactions of different species.

I would like to end this walk with a poem on lichen written by Pablo Neruda called Lichen on Stone.

Lichen on stone: the web

of green rubber

weaves an old hieroglyphic,

unfolding the script

of the sea

on the curve of a boulder.

The sun reads it. The mollusk devours it.

Fish slither on stone,

with a bristling of hackles.

An alphabet moves in the silence,

printing its drowned incunabula

on the naked flank of the beaches.

The lichens

climb, higher, plaiting and braiding,

piling their nap in the caverns of

the ocean and air, coming and going,

until nothing may dance but the wave

and nothing persist but the wind.

References

Osiewacz, H. D. (2002). Aging in fungi: role of mitochondria in Podospora anserina. Mechanisms of ageing and development, 123(7), 755-764.

For more information on Anne Pringle’s research, check out this video or the article:

Pringle, A. (2017). Establishing new worlds: the lichens of Petersham. Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene, G157-G167.

Your feedback

I would appreciate your feedback – positive and/or negative – on the walk. You can access a questionnaire here. It won’t take you more than 5 minutes! Thank you in advance.

Contacts

Thank you again for your participation. If you find other lichen species that you have identified, or would like help with identification, please contact me at lichenwalk@gmail.com.