Yes, and you, too. Also you. And you. And you over there at the back. Don’t look away, and as you read, reflect on how you’ve used your entrepreneurial skill set in your academic career.

“I don’t have an entrepreneurial bone in my body,” the researcher said to me. I was startled. This person just shared their career story with me, where I learned:

They identified a problem (a ‘gap in the market’, as it were) in their field of study and developed an idea that could solve this problem.

Most problems in academic research are ‘open ended’- they have a large problem space and the method to solve them isn’t clear. Like all researchers, this researcher had to embrace risk-taking to tackle their all of their research problems.

This post-doc persuaded a funding body (‘investor’) to support their approach to solving a side-problem to their main research and successfully attracted funding (‘investment’) by writing a persuasive small grant proposal (marketing and financing). Even if a post-doc hasn’t successfully applied for a grant, they will be working to a budget. A travel grant still requires marketing and promoting the value of travel to a potential investor in that researcher’s career.

At various stages of their career, my researcher career had participated in various public engagement activities (presenting their ideas to stakeholders) and other forms of effective communication.

As they recounted their story, it was clear the research hadn’t always gone to plan. To achieve outcomes, the researcher had to be determined and resilient. Successfully solving planned-for and unplanned-for problems demanded creativity.

Throughout their research, they had to make decisions based on budget resource, time resource, sustainability of their methods and more to make sure, ultimately, their research decisions were good value for time and money.

Since deciding to do a PhD, they had been responsible for hundreds of decisions, taken ownership and accountability for ideas and actions, defending all of these in various formal and informal fora. They had supervised the intellectual development of undergraduates and masters students. In short, they, like any other post-doc (including you, reader), exhibited the skills of leadership.

There are lots of different ways to be an entrepreneur. Yes, it can be setting up your own business. It can also be leading or promoting innovation within a place of work (‘intrapreneurship’ was the buzzword a decade or so ago).

Also, don’t fall into the trap of thinking it’s an extrovert thing. I run a successful freelance consultancy as a super-dedicated introvert. Which is a final point – researchers are at their best when their sense of purpose aligns to their research. Entrepreneurship is the same – we’re at our most innovative and motivated when the goals of our resourcefulness mean something important to us, aligning with our values, interests, and sense of purpose in life.

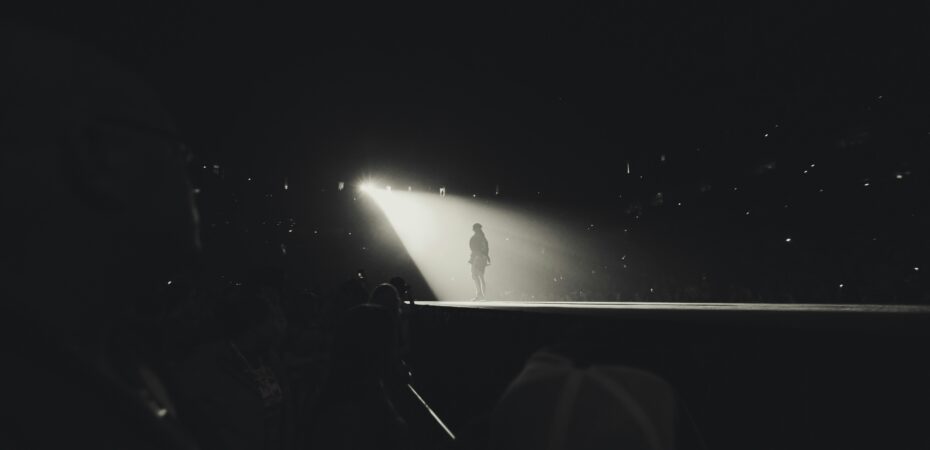

If none of that persuades you because, perhaps, of the images the word ‘entrepreneur’ brings to mind, it might be helpful to know that the very first entrepreneurs were the creative people managing and promoting theatrical stage productions -sources of joy, relief, escape, intellectual and emotional stimulation, fun, resistance, experimentation – demonstrating that in entrepreneurship, there can be something for everyone.