Being on the universities research ethics and integrity review group (REIRG) has me pondering how I, as an academic developer, can make training on research ethics and integrity effective. The way I see it, no training is effective until:

- the participant sees the need for the training,

- the training is flexible enough to allow all participants to use it,

- is a positive experience, and not one where you feel overburdened or criticised.

To me, all of these key elements for training become particularly difficult to meet with research ethics and integrity. Partly this is because there can often be a perception that doing training on ethics and integrity means that you lack them in your research. The language and wording used around research ethics and integrity are not helpful either. Words like pitfalls, misconduct, compliance, make it feel like a trap of some kind to catch you out. So how can we possible create effective training when the culture surrounding ethics and integrity is so negative to start with?

First of all, we need to change the culture so that the training on research ethics and integrity becomes something that you think will enhance you and your research, rather than something you do because it might be mandatory. Research ethics and integrity training is about putting the spotlight on all of the excellent research that goes on, and nudging it a bit to make it even better. It’s about improving what’s already good to make it excellent. It’s about equipping you with the knowledge and space to think about why you do your research in a certain way, and how you might be able to do it even better.

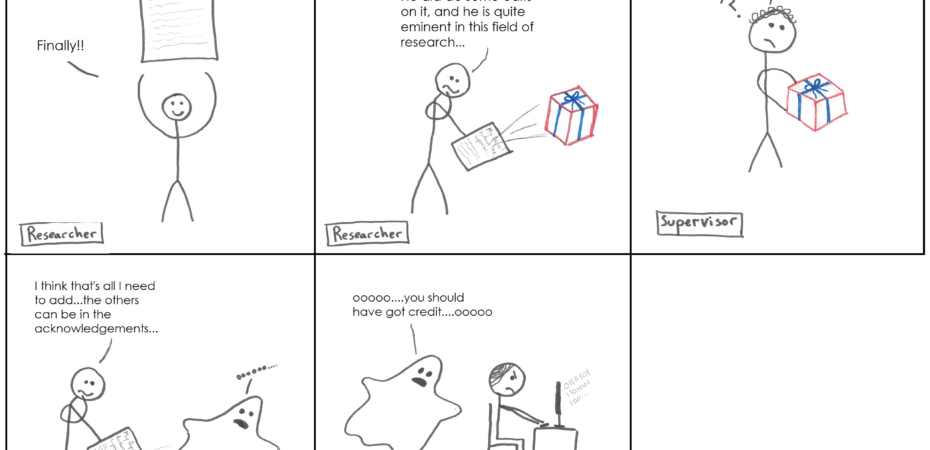

It can also be surprising. You may find that something you thought was common practice might not be such a good idea. A good example is authorship and publication ethics. I’ve included an illustration I drew of a scenario that might not be too far fetched (inspired by xkcd and some great infographics from the Office of Research Integrity).

How many publications do you have experience of where authorship is either a) not warranted (i.e. gift authorship), or b) misses out people who should be given credit for their work (i.e. ghost authorship)? Deciding who should be an author and what merits ‘significant contribution’ on a publication is a tricky business, and varies hugely between disciplines.

Perhaps you’ve thought of publishing your paper, but aren’t sure what the conventions for publication are. If you’re new to publishing, you might think that submitting to two journals at once makes a lot of sense. How are you to know that this wastes journal resources (reviewers, time and money) and gives you an unfair advantage over other researchers? No one could possibly know all the ins and outs of what’s good practice without some guidance. Ethics and integrity considerations are many and varied, and are not something that stops after you have completed your ethics reviews, but appear along the whole research cycle from start to finish. Even senior researchers are not exempt from stumbling on complicated issues.

Perhaps you’ve thought of publishing your paper, but aren’t sure what the conventions for publication are. If you’re new to publishing, you might think that submitting to two journals at once makes a lot of sense. How are you to know that this wastes journal resources (reviewers, time and money) and gives you an unfair advantage over other researchers? No one could possibly know all the ins and outs of what’s good practice without some guidance. Ethics and integrity considerations are many and varied, and are not something that stops after you have completed your ethics reviews, but appear along the whole research cycle from start to finish. Even senior researchers are not exempt from stumbling on complicated issues.

This depicted scenario is perhaps not too far from reality, and you can see why the researcher might be making the decisions they have. Adding someone with ‘a name’ in your field to your publication can give it extra kudos, and forgetting to add someone who might have given you data, but who you’ve never actually met, can be easily done. Similarly, it makes sense to submit to more than one journal, especially if the turnaround time for review is very long and you need to publish it ASAP.

Good training should not be designed to make you feel bad or put you in the spotlight. Quite the opposite, all it tries to do is get you to realise what good practice is, and then use it if you aren’t already. That’s all. Easy really, but first you need to realise the need for research ethics and integrity training, and then take from it what you need to improve your research. Crucially it needs to fit all sizes, and this means providing it in parts with short useable information that is directly relatable to you. Infographics are a great example of that. A broad-brush approach is only helpful if you are starting from scratch, and this is rarely the case. Most of us are already using good practice, even if we don’t exactly think about why we do it in that way (e.g. the scientific method). I hope that any training you do will only highlight what you are doing well, make you realise what you’re not, and help you to improve it!

This blog post was written by Emily Woollen, an academic developer in the researcher development team at IAD. The opinions expressed in this blog are all her own.