I’ve been running research leader/principal investigator development programmes for over a decade in universities. As part of these we invariably get in a couple of senior academics to talk about their backgrounds and share advice with those taking the first steps into group leadership. Two particular talks have stuck in my mind, both at Newcastle University and both related to funding.

I’m embarrassed that I can’t remember the name of the first academic, but she appeared with her slides and began to talk about her funding portfolio. Each slide had a list of proposals she’d written against the dates. There were about 4 slides, each with 7 or 8 proposals listed. She talked about the range of projects and how her ideas had developed over time. Then she paused. She went back to the first list and explained that she was about to share the most important lesson she had for the group.

The slides now included whether the research was funded or rejected. All the proposals on the first slide were rejected. As were all on the second slide. She got 3/4 down the third page before we saw a “FUNDED” and the whole room cheered. Then the next proposal… REJECTED. Eventually the tide seem to turn and on her final slide there were more successes than failures. She said that we had to remember this. That the competition for funding was such that we had to persevere and that she was honest enough with herself to know that some of her success was down to the fact she was still trying.

Fast forward a few years and another speaker comes in. Professor Mike Trenell sits down with the group and proceeds to tell us not about the ~£7.5 million he’s brought into the University, but the ~£35 million that he didn’t. He talked about all the moments in his career when he did the wrong thing and the fact that failure is a part of research and you have to learn to accept it and learn from it. He told us about how he felt when things were going wrong and the support he had which kept him going.

These two talks had a big effect on me and I hope they helped the audience of new and aspiring academics, particularly at moments in their subsequent careers when things went badly. In my previous role I used to run workshops on funding, getting started in research and moving on from postdocing into new careers. There is a lot of failure wrapped up in these topics, so I made sure we talked about how to cope with it when it came.

A few things have popped up on twitter this week – the mental health awareness hashtag is throwing up all sorts of gems and I hope we continue these conversations next week. One that particularly resonated was a link to an opinion piece in the Journal of Cell Biology from 2008 entitled The Importance of Stupidity in Scientific Research by Martin Schwartz. In this, Professor Schwartz talks about the two disservices that the scientific community does to young researchers – not talking about how hard research is and not teaching students how to be “productively stupid” so they have the confidence to wade deeper into the unknown. I wish I’d read this as a PhD (impossible as it would have required a time machine. Ahem.) because I was incredibly tentative with my steps into the unknown and can recall a meeting with my supervisor where he expressed frustration about the fact that when he challenged another student about his ideas, that the student “folded” and backed down. At that moment I realised that all of the criticism of my ideas I’d faced from him was part of his supervision – I needed to be able to defend my thinking or fix its flaws if I was going to have the confidence to wade deeper. Some people reading this will think I should have realised this sooner, but I didn’t – I thought he was criticising my ideas because they were rubbish. My attitude to my PhD shifted in that instant. It was OK to be stupid and wrong because that was how I would learn (and I was probably neither).

I had another reminder of my failures last week as I walked to Burlington House for the RSC conference. As I turned out of the train station my view was filled with the Grant Thornton building, then I walked through various bits of UCL. One the way back I diverted via Parliament Square. Each of these were landmarks on my failure map (there’s a lot of them). I was rejected from pretty much every accountancy firm in the UK in my final year but I remember the Grant Thornton one because I was rejected for writing an application form in blue ink (their form was printed blue so I thought it looked better…) During my last postdoc, I didn’t get a job at UCL as a careers adviser, having previously failed to get a job as a researcher in the House of Lords. At the time each of these rejections really hurt, but they meant that I was available for the opportunities that followed. I can’t go back and tell my former self that it will be OK, but I do take every chance to tell students and researchers that there are lots of options for them.

Researchers and research leaders are becoming more at ease about sharing failure, but there was a lively discussion at last week’s event about the rhetoric that you have to present in science all the time. You have to be bombastic about your ideas, your uniquely wonderful track record and present a confident picture of the world leader you will become. Some people realise that this is “part of the game” but many struggle to exaggerate their achievements and deselect themselves from opportunities that seem to demand superhuman qualities. Hopefully the funders in the room were listening to this and went away considering how to shift the tone of their calls to be more appealing to people who don’t think they are transcendentally marvellous.

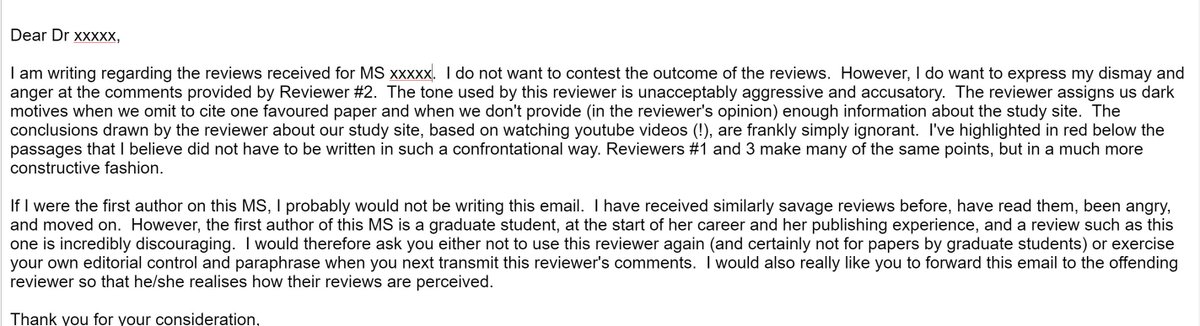

As always, there are things we can do as individuals (talk about our failures and reassure those who aren’t successful that it’s expected and accepted), but the research “infrastructure” can do more. My final thought comes from a tweet that got a lot of attention last week from journal editor John Hayes on the subject of journal reviewers. He retweeted an earlier message from Isabelle M Côté who had highlighted the aggressive tone of a reviewer’s comments.

Now properly cooled down, I sent this to the editor who transmitted a savage review. Let’s bring civility back to peer review!

— Isabelle M Côté (@redlipblenny) December 13, 2016

Like yesterday’s suggestion that organisations who badge conferences have the power to insist on organisers taking steps to make them more inclusive, could journal editors take steps to ensure that feedback is constructive and objective? It’s OK to fail, but not easy. We don’t have to make it any harder.