This is our first guest post on iad4researchers and I’m delighted that Dr Kay Guccione (@kayguccione) at the University of Sheffield took the time to share her perspectives on the valuable role postdocs play in supervision. Unless there are factual errors I won’t be making any edits to our guest posts, so their views are their own.

Postdocs view experience in supervision, teaching and learning as core to scoring that academic career (Akerlind 2005). And post-doctoral research staff are actually very active in teaching and learning*. I believe that post-docs are a really important but often under-recognised group of teachers in research intensive universities. Development of an academic sense of self is in part a result of having the right formal institutional responsibilities and resources (McAlpine et al., 2013) yet, post-docs aren’t often included directly in university Learning & Teaching strategies, or seen as key assets with specific skills, position, and the right experience to teach. So, the work they do tends to be under the radar, informal, ad hoc, and without formal permissions or structures in place that recruit, recognise or reward post-doc teaching. It’s not always included in the post-doc job description for example, or during the annual appraisal systems. Yet, the sector en masse believes it’s a function that post-docs, if they want to progress their careers, should be engaging with — it’s right there on the Researcher Development Framework. And it comes up at interviews for lectureships too, to a greater or lesser extent depending who’s interviewing.

Often I speak to post-docs who complain they can’t get ‘supervision experience for their CV’ — but any opportunities we create for post-docs to be supervisors have to be about much more than a line on a CV. If we want to promote the concept of ‘World Class Supervision’ (which DOES get a mention in Learning & Teaching strategies), departments need to stop employing academic staff who are just great at research.

So, where do early career researchers learn not just how to ‘do supervision but also what it’s like to ‘be a supervisor in a university setting. Not just enough to ‘get the job’, but to actually ‘do a good job’? Not by the solo act of attending a workshop (which is a good start) but by actually putting in the hours of supervision practice that embeds real understanding. By doing academic work for real, on the job. Look at the list below again, the top five on the list are real supervision experiences.

Supervision is a form of 1:1 teaching, and like all teaching, in order to become good at it we need to practice at it, in a self-aware way. The best way I know of becoming aware of what you know, what you’ve done, why, and how, is to apply for nationally recognised accreditation as Fellow or Associate Fellow through the Higher Education Academy. At Edinburgh the link to find out more is here (SS note – and we welcome the chance to support postdocs through our teaching programmes.)

So how can early career researchers learn not just how to ‘do supervision’ but actually how to ‘be a supervisor’.

At the University of Sheffield, I designed a Thesis Mentoring programme where the mentors are post-docs, trained in mentoring. They meet fortnightly with their mentee over 16 weeks and they discuss everything to do with the practices of academic writing — from how to overcome negative thinking, to how to integrate data with the literature, to how to create a writing plan you can stick to, to how to get the feedback you need from your supervisor in a timely way. They help PhD writers chunk the task down, focus on what they can achieve, and figure out what works for them.

Mentors tell me that after participating they feel more confident helping PhD writers in their own groups and departments. They also tell me that they feel way more informed about what support PhD students need, how to motivate them, and how to deal with difficult issues. Sounds like World Class Supervision to me.

Perhaps you as a post-doc don’t have a similar programme to belong to? How you can emulate this without the institutional structures in place? Below are guidelines for setting yourself up as a thesis mentor:

- Read your university’s PGR Code of Practice on thesis writing so you know what the rules are.

- Research ‘what do mentors do’ (and see the video below) — often mentoring is equated with advice giving, but also think about a more sophisticated repertoire beyond just giving advice. Read here for some ideas about what Sheffield mentors do.

- Decide how much time can you give to this — how many 1h sessions per person, how often, how many mentees?

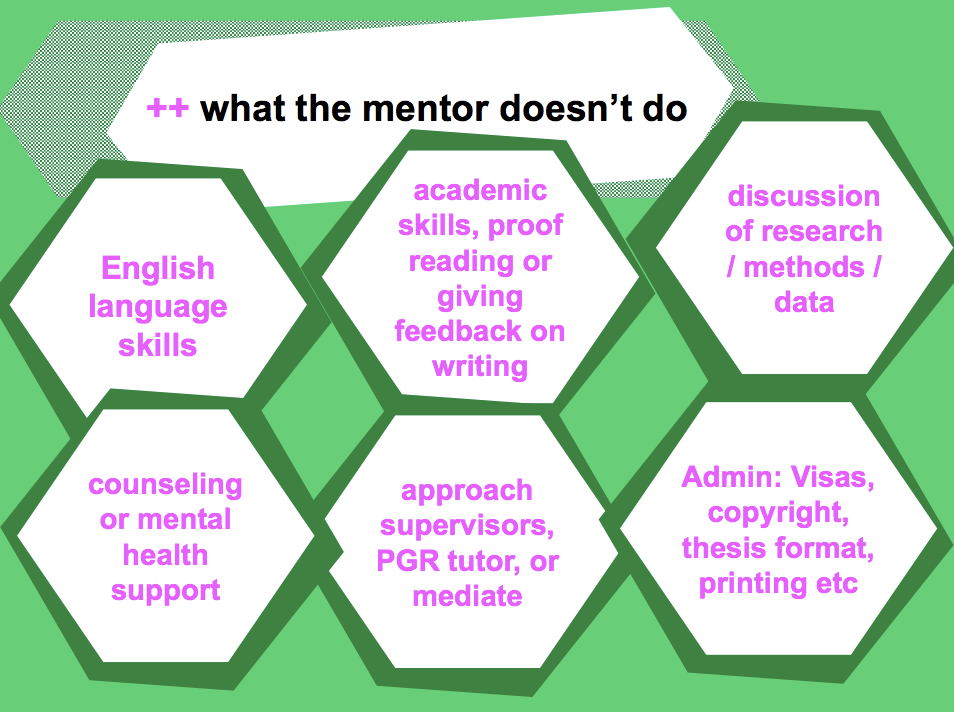

- Decide what you won’t cover as part of your mentoring — be ready to signpost to other places at your university that cover the things you can’t (see image below).

- Create yourself a template ‘agreement form’ so you can set out with each mentee with a clear set of expectations (one is shared with you here).

- Email PhD writers in your dept. and see who’s interested, arrange to meet on campus.

- Don’t forget to ask them how they’re finding it and get their feedback before your next session.

For universities to do this properly we have to look around at the value that research staff offer to our teaching & learning, and supervision strategies, and put structures in place to enable our future visions of excellent supervision. Rather than viewing post-docs as unqualified amateurs, having a play at teaching to get the experience, recognise there are teaching jobs in universities that ONLY POST-DOCS can do. Thesis support is one of those things.

But until we change our institutional approaches to recognising the value of post-docs, it’s up to you to navigate and familiarise yourselves with the work you will be doing every day as an academic member of staff.

*teaching is way more than standing a lecture room spouting off.

- In the lab teaching new people techniques, making sure they’re competent and safe

- looking over the data students generate and helping them interpret

- tutoring informally e.g. supporting people who are new/feeling pressure/struggling with writing etc

- managing project students

- giving feedback to peers and students on their ‘practice’ presentations

- running a journal club, especially if you facilitated a discussion, wrote guidance etc

- facilitating on undergrad/masters/doctoral modules e.g. research methods or research ethics

- second marking, or substitute marking, or unofficial ‘please help me’ marking

- peer mentoring of colleagues

- writing for a research-communication blog

- doing outreach or public engagement — teaching different audiences

- running an event where you have thought about how people will learn something e.g. inviting a career talk and providing guidance to the speaker

- designing an evaluation that feeds back into design of the next event or opportunity

- contributing to learning & development agendas, e.g. being active on a post-doc committee that steers the work of researcher developers

- Contributing to a network designed to share learning or knowledge e.g. a software users group.

McAlpine, L., Amundsen, C., & Turner, G. (2013). Identity-trajectory: Reframing early career academic experience. British Educational Research Journal.

Åkerlind, G. S. (2005). Postdoctoral researchers: Roles, functions and career prospects. Higher Education Research & Development.

SS note: If you know of good practice or ideas in Edinburgh or other institutions that we could feature here, please let me know. If you want to suggest a topic or author for a post, I’d be delighted to hear from you and I’m happy to reciprocate if of mutual benefit.

Great article, thanks. Just as a reminder, although its aimed at a general population, there’s lots of great information for mentors on the UoE Mentoring Connections webpages – loads of advice, guidance and tools which would help with this process. http://www.ed.ac.uk/human-resources/learning-development/dev-opportunities/mentoring-connections

Reblogged this on Think Ahead Blog and commented:

Guest post on the University of Edinburgh IAD4RESEARCHERS blog

Reblogged this on predoctorbility.

[…] and from those supervisors who contribute free emotional labour. I am currently researching thecontribution of postdocs to supervision, and how postdocs develop as supervisors through formal structures and opportunities. I’ll write […]