Lecture 3: Religious Networks in the Age of Empire in New Spain and Africa

A full Playfair library greeted Professor Hempton on Thursday afternoon. Below is a summary of the lecture, two responses, from a PhD candidate in African Studies Francisca Anita Adom-Opare, and an undergraduate in the School of Divinity Andrea Azzurra Melani. The video recording will also follow.

This lecture juxtaposed two religious networks that emerged in the age of Empire. The analysis shows that networks can be understood and presented in different ways, spread by the most marginal and unlikely of characters and transcend their original purposes.

‘As these forays into religion and empire in the Americas and Africa make clear, Christianity through its collaborative and subversive alliances with imperial power, whether Catholic and Iberian or Protestant and Anglo-American, has the capacity to deliver popular cultures of devotion of extraordinary power, durability, and transmissibility and also perpetrate cultural rape and cruelty of unimaginable proportions. No evaluation of the balance sheet, however uneven it may be, can rest on the ideologies and actions of hierarchical elites alone, but has to take into account networks and nodes, some of which are surprising and hidden from view.’

Beginning with Catholicism in the Iberian Empire in New Spain, Hempton focused on devotion around material and often tangible shrines and images. The most significant images and shrines are those of Our Lady of Guadalupe that spread across Mexico and in Latin America. From its supposed beginnings at Tepeyac in the early sixteenth century, to its annual feast-day celebrations in the 1690’s to its ‘vigorous efflorescence’ after Pope Benedict XIV’s papal bull of 1754, Marian devotion in colonial an postcolonial Mexico saw ‘the image transcended its geographical and temporal specificities and did not depend on establishing Tepeyac as the centre of a dominant tradition of pilgrimage.’ It transcended also the shifting political power shifts in Mexico’s struggle for independence and serve a nationalizing purpose, becoming, according to William Taylor ‘the temple of the national religion.’ Hempton admitted that this network of Our Lady of Guadalupe challenged his own understanding of how religious networks operated in the intersection of Empire builders, religious institutions and indigenous receivers. Instead of this network having a hierarchy of placed, fixed routes and central spaces acting as nuclei, this is a fluid, personal, connecting practice. ‘[T]his is not primarily a network/web of pilgrimage routes or of well-orchestrated colonial or ecclesiastical propaganda, but rather a loose federation of sensuous devotional sites dedicated to images and apparitions of the Virgin Mary, Christ and the Cross, and the saints of the church.’

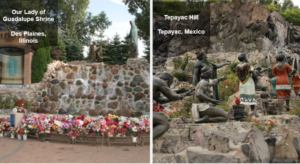

This tangible Guadalupan network also moved with it devotees, Mexican migrants carried it to other parts of North America and far beyond. The world’s second most visited Guadalupan shrine is in Des Plaines, Illinois. It has a digital copy of the original image from Tepeyac and imposing sculptures of the Virgin and Juan Diego. This also links the migrant with the home communities. Elaine Peña has demonstrated that through their role in daily rituals, as centres in festivals, pilgrimages and devotional piety, they enable devotees to be ‘transnationally linked by doctrine, tradition, aesthetic/physical replication, and early-twentieth-century labor circuits.’ A key part of this network therefore is its ability to inspire, empower and connect the community. ‘It reflects and negotiates colonial conquest, religious authority, and indigenous and ethnic solidarity; it both reinforces local loyalties and transcends national boundaries; it has a unified core of doctrines, aesthetics and devotions, but it attracts ‘devotional capital’ from many different experiences and motivations; it is not repudiated by religious authorities, most of the time, but sometimes creates problems of control for ecclesiastical institutions; above all, it powerfully unites Latin American Catholics in a loose but sensuously evocative federation of faith and culture.’ The material objects, in their ability to move with pilgrims and create a ‘real presence’ of piety show that they do not just travel across networks but constitute networks themselves.

This network is also beginning to become rooted in other contexts, from Mexicans arriving in Chicago from the 1920’s, the Archodiocese of Chicago now has Spanish language masses in more than a third of its parishes. Each year over twenty million pilgrims travel to the Virgin of Guadalupe’s shrine at Tepeyac. They also travel with their own replicas, images and portable shrines. Jennifer Scheper Hughes, analyzing these, shows how the body is being used as a mobile

altar, that carries replicas to draw from the power of the original. This also reflects a pre-conquest practice of ‘god-bearing’ in Mesoamerican religious practices. These around 500 shrines constitute a network of devotion, capable of translocal expansion, sometimes supported by and sometimes repressed by ecclesiastical elites. ‘They were places where the immaterial divine could be encountered through material representation of the virgin, the crucified Christ and the historic saints offering hope and protection against the dangers and vicissitudes of daily life.’

altar, that carries replicas to draw from the power of the original. This also reflects a pre-conquest practice of ‘god-bearing’ in Mesoamerican religious practices. These around 500 shrines constitute a network of devotion, capable of translocal expansion, sometimes supported by and sometimes repressed by ecclesiastical elites. ‘They were places where the immaterial divine could be encountered through material representation of the virgin, the crucified Christ and the historic saints offering hope and protection against the dangers and vicissitudes of daily life.’

Andrew Walls’ book on a PhD candidate’s desk in Divinity

Our second case study is one familiar to the School of Divinity in Edinburgh through the work of Andrew Walls, the founder of our Center for the Study of World Christianity. Hempton explains the networks in Sierra Leone- a node that draws together the British Empire, Nova Scotia, and African Christianity intensely. The Protestant evangelical missionary slogan coined by David Livingstone of ‘Christianity, commerce and civilization’ was employed in the context of Sierra Leone to create a hub fir an idealistic freed-slave community that could transform the whole African continent. The voluntary foreign missionary model also relied upon other networks, most notably the British philanthropic networks to support their endeavors, sometimes even the Boards of the Bank of England and the East India Company, and interestingly, the backbone of these networks were the Dissenting and Methodist traditions, excluded from full participatory life in Britain but more than willing to serve in its ‘godly mission’ abroad.

‘Central to that godly mission in the decades after the loss of the American colonies was a powerful combination of antislavery mobilization, missionary zeal, commercial ambition, and civilizational hubris.’ Sierra Leone became the most important node for the vision. The second attempt at this vision that is, Sharp’s 1787 ‘Province of Freedom’ was a ‘grim failure.’ Five years later, the endeavour was more successful, due to the partnership with another network in the American colonies and Canada. This was the period of the emergence of black Christianity, and Nova Scotia was a melting pot of its distinct but united forms (not unlike the Azusa Street community). The dislocation of the American Revolution saw black migration to Savannah, Charleston and New York, and these pastors eventually spread to Nova Scotia and the Caribbean Islands. Black empire loyalists were recruited from Nova Scotia to make the reverse journey over to Africa, most of the 1,100 men and women being freed slaves to ‘civilize and Christianize a great Continent, to bring it out of Darkness, and to abolish the Trade in Men’ as recorded by Thomas Clarkson at the time.

‘Here was a migrating network of onetime slaves forged out of imperial failure and revived by the transatlantic spread of populist evangelicalism.’ One exemplary figure explored by Hempton is David George. George was born a slave in Virginia in 1743 and revived in South Carolina before the American Revolution. He became the first Black Baptist pastor in both Canada and Africa. George had a multitude of influences, the spirituality present in the South colonies in the 1760’s and 70’s, the (deeply flawed) white Christianity of the plantation owners, and the piety of slave believers and New Light Baptist preaching. George’s illiteracy did not prevent him being confident in his conversion to Christianity, later exclaiming that the bible reaffirmed what he had in his heart in scriptural form.

The Sierra Leone project from 1807 was under British colonial control, who used the terms Christianised and civilized interchangeably and attempted to transplant a European village and parish network into Sierra Leone, but there was no one set Christian tradition, or authority figures (only missionaries from voluntary societies). The parishes- named after British people and towns- instead reflected a black diaspora, where Western and African ideas intertwined and were influenced by Christianity, Islam, indigenous traditions, and 120 languages! The network that was trying to control was not the dominating network in this example. The Western missionaries were not the only ones evangelising, and instead of the colonial Christianity being exported, instead evangelical forms of Christianity were being indigenised, flavoured and revitalised by the Nova Scotian migrants. Zachary Macaulay, despite his anti-slavery agenda, regarded George and his contemporaries as ‘a most ‘seductive’ creed in which there were ‘No means to be used, no exertions to be made, no lusts to be crucified, no self-denial to be practiced.’ Instead, they constructed their faith round instantaneous conversions, ‘inexplicable mental impressions and bodily feelings,’ and the ‘delusive internal feelings of a corrupt imagination.’ For Macaulay, God’s evangelical Kingdom in Africa was not to be curated by Africans. Hempton reflects that, ‘[w]e should not underestimate the energy and achievements of both Wesleyan Methodist and Church Missionary Society missionaries and others in building schools, colleges, churches and parochial discipline in Freetown and the surrounding villages in Sierra Leone, but over the long run the realities of colonialism set their own limits.’

Professor Brown ended the question/answer session by reflecting on how the fluid network of Guadalupian devotion was more successful than the British attempt to transplant networks into Sierra Leone. Indeed, it seems the nuclei has a very important place in ensuring the longevity of networks. Hempton advised that when examining Christianity in Africa today, ‘Christianity does not have to come encased in centuries of European civilization.’ Dr Wild-Wood, an expert on African indigenous religions and African Christianity, reflected after the lecture that the networks built in Sierra Leone did not end here. She explained that the link between these African migrants from Nova Scotia directly continued their work to influence the larger continent in Africa, believing the current reality of Africa being the centre for Christianity in the world today is directly linked to this story. To conclude, this lecture has exposed us to the uncontrollable reality of successful networks, where nodes of encounter inspire nuclei in devotees who take the network into new, unexpected directions.

Reflection 1

Fluid Identities and a Contextual Response

I was unable to attend the lecture (in-person and online) due to a family emergency, therefore my reflections stem solely from the full paper on the lecture. Again, coming from a background outside theology and philosophical thought, my reflections and accounts may seem skewed towards Africa and naïve to experts within these fields, nonetheless, I hope that my layperson’s perspective emanating from my lived experiences as a Catholic and Protestant provides useful insights. Furthermore, I must say that it is a sheer coincidence that the lecture on “Religious Networks in the Age of Empire in New Spain and Africa”, focusing on Catholicism and Protestanism mirrors my religious journey.

My reflections, as stated will centre on my personal experiences as a Catholic growing up in Western Africa and as a Pentecostal in my latter years, yet I self-identify as a Catholic. I would say here that although Catholicism and Protestantism have stark differences, their ultimate connection is falling under Christianity with divine reference to God.

Professor Hempton’s lecture provides a great visual periodical layout of historical events with foci on networks, nuclei and nodes within Catholicism and Protestantism in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa respectively. This made a fascinating reading!

The first part of the lecture by Hemptom talks about Catholicism with main highlights on the material and often tangible shrines and images with which I strongly identify with. I was an altar girl (mass server) growing up. The Sacristy (the place where scared materials such as the Candles, Cross, Bread, Wine, Thurifer-metal container that holds the hot coal, Bolt-metal container that holds the incense, Incense, Holy Water, Priests’ Chasubles, and Robes, etc) was a revered place, and we (mass servers) counted ourselves privileged to have had the honour to handle these materials. The historical accounts of these tangible shrines and images allowed me to appreciate the breadth and expansion in our twenty-first century.

Secondly, reading the manuscript from Professor Hempton brought back memories from my family house. In my family house, there was a sacred table (“shrine”) with images of Jesus Christ, Our Lady of Guadalupe (in West Africa, we will say “The Virgin Mary”) with Candles, Rosaries, and other scared materials. Although all the materials on the table were sacred, I realized that some were of more value than others primarily because of their origin. For example, the Rosary was purchased from Rome (The Vatican-“the Holy Land”). Due to its origin extra care was placed when handling it. These sacred tables are held with utmost importance and had been passed on from generation to generation. This goes to support Hempton’s assertion of the mobile body, which moves beyond the body to sacred materials.

Thirdly, appreciating the history of Catholicism illustrated here by Hempton allows one to situate her/himself in time and appreciate the networks and the body used as a mobile altar. The networks of Guadalupian devotion arguably is widely spread compared to that of Protestanism in Sub-Saharan African. I could argue that the sacred materials found in Catholicism have been refashioned with similar materials used within Protestantism, showing interconnectedness within religious networks. Moreover, it is not surprising therefore that in National Censuses, Catholicism as a religion is separated while in most cases all others within Protestantism (Methodist, Presbyterian, Pentecostal), etc are lumped up into one. This shows to some extent the propaganda and networks within these religious networks. With my theological and philosophical naivety, I could conclude that there are two broad categories: Catholicism and Protestantism in Christianity which Hempton historically articulates; and therefore, a timely lecture in the twenty-first century.

Furthermore, the account of Tepeyac allows the reader to journey through time and appreciate the Virgin of Guadalupe. In adding to the nineteenth-century European catholic migrants from Ireland, Italy, Poland that saw masses being said in Spanish, this is also true where currently in West Africa and Scotland, some masses are said in Latin and Polish respectively, which goes to show the remarkable diverse mix of national groups and generations of migrants that continue to exist today as Hempton asserts.

Additionally, on nodes and nuclei, like Tepeyac, most Catholics would make an annual pilgrimage to holy places such as the Vatican. Similarly, Protestants would make pilgrimages and/ to Israel or Jerusalem. During such visits, sacred materials such as Holy Water, Sand and Rosary are cherished materials held onto for ages. Pilgrimages from the peripheries to centres to some extent do sustain networks in our twenty-first century as well.

Lastly, on Catholicism, I do not entirely agree with Professor Hempton, when he states that “there is not a well-orchestrated colonial or ecclesiastical propaganda, but rather a loose federation of sensuous devotional sites dedicated to images and apparitions of the Virgin Mary, Christ and the Cross, and the saints of the church”. From my personal experience in Sub-Saharan Africa and currently the UK, I believe both are true: well-orchestrated propaganda and loose federation coexist. Why? For instance, attending a Catholic school, one would see both Catholics and non-Catholics wear Rosaries for reasons best known to them in Africa. Also, during my time in high school, it was a norm that on entering the Catholic chapel mandatory genuflects are made; those who do not are termed as deviants. This to some extent goes to show that regardless of a visual appeal, there is ecclesiastical propaganda.

Now, focusing on the second narration on Protestantism which dwells on the nucleus of Christianity, Commerce and Civilization. Christianity in my opinion has outrun the other Cs currently. The striking historical narration of the British Empire, evangelical Protestantism, and the Christianization of African expressions amidst a mixture of religious elements, Muslims, Christian and indigenous presents some hidden elements with the establishment of Protestantism. For instance, in most parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, when two people are getting married, two ceremonies are held. The traditional wedding (indigenous) and the white wedding (Christian). In most cases, the traditional wedding is not as flamboyant as the white wedding. This speaks to the cultural rape in Hempton’s concluding remark which allows us to question the interplay between indigenous culture and Christianization historically and presently.

Again, I do agree with Hempton when he states that “Christianity does not have to be regarded as a mere extension of Western norms”. Nonetheless historically and presently this is largely the case in Sub-Saharan Africa. And I will refer to my earlier example on marriage. During most Sub-Saharan African marriages, the woman is dressed in white/cream/ivory fairy attire with the man in a suit and tie, mimicking Western culture. However, now due to decolonization people are beginning to accept the fact that one need not necessarily wear Western attire during the white marriage. Yet this is a hard pill to swallow as some people are shunned as from low-income backgrounds should their white wedding deviant from Western attires to indigenous attires.

In conclusion, Professor Hempton’s lecture has illuminated the (un)controllable reality of successful networks, where nodes of encounters inspire nuclei and unexpected directions. I believe it is a timely lecture in our century as it shows the diversity and interconnectedness of Christianity and the extraordinary power it wielded historically and currently wields.

Reflection 2

Objects as Networks

It has been an honour to attend the Gifford Lectures, delivered by Professor Hempton, during my undergraduate journey. I am not approaching his series of lectures as an expert in any specific field of research, rather what I am more interested in is trying to understand his perspective and networking method to support me in this early stage of my academic progress.

I will primarily focus on the first part of Professor Hempton’s lecture. He identifies a network system among Latin American devotionalism of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Although, before deepening his research, Hempton acknowledged that at the beginning he had a clear idea of how the networks, nodes and nuclei presented in the previous lecture regarding the Reformation Era would fit within this Southern American context, especially looking at pilgrimages to Mexico City and Tepeyac, and at the devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe as nuclei. Unfortunately, what he expected to find was not there. Instead, drawing out from William Taylor’s research, Hempton recognises that pictures, reproductions, paintings, and shrines of Our Lady of Guadalupe are those nuclei that constitute this network. His bias awareness and subsequently willingness to reshape and redefine them are an inspiration for a young student as I am.

To develop this session, based on Deborah Kanter’s work, he analyses how the devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe transcended geographical limits. Building on Mexican immigration to Chicago from the 1920s, Mexican Catholic Churches became an important community centre where Chicago Catholicism and Mexican devotions, including Our Lady of Guadalupe, fused. What Hempton identifies as core point to this interaction consists in the “way in which the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe was at the centre of parish churches,” hence, her reproduction somewhere else than in Tepeyac, acquires, in Thomas Weed’s words, translocative potential. Lastly, he looks at the significance of modern pilgrimage. People from all over the world devoted to Our Lady of Guadalupe go on pilgrimages to Tepeyac believing that the power of their representations of the Virgin will reactivate through encounter with the shrine at Tepeyac, expressing again the translocative quality of images.

At this point I want to bring the attention to a reflection that has been raised during the Question-and-Answer session: what should we think about the relation between network and places, as it seems a tendentious one? In his answer professor Hempton explained that on one hand the devotion of Our Lady of Guadalupe is closely connected with images that are rooted in precise local areas that attract pilgrims from all over the world, but on the other the reproductions have the power to be relocated in different regions and develop their own devotional power. Therefore, as a network should be located in particular places and simultaneously possesses the potential to transcend these places, it might be interesting to keep in mind what the a priori characteristics are that a network should possess in order to be able to be meet these two contrasted potentialities in the lectures that are to come.

One last personal reflection regards the feasibility of this network of objects.

Objects has always played an important role in Christian life, whether as mere symbol or as carrier of divine presence, whether for ordained people as well as for laity. It might be interesting, as subject of a further study, to find other patterns where this network of objects can offer new insight. What comes to my mind is the devotion to St Francis of Assisi throughout Italy, not just his images and reproduction, but his cross. The cross of Assisi, in Italian culture, plays a specific role in devoted people’s life. People recognise it from its singular shape, and it generates a sentiment of connection to the Saint, the town of Assisi (which they might have pilgrimages too) and the people that own it. Therefore, the network of objects that Professor Hempton identifies in Devotional Latin America and Chicago, might be also applied in modern day Italy to reveal nuances of this phenomena.

Objects has always played an important role in Christian life, whether as mere symbol or as carrier of divine presence, whether for ordained people as well as for laity. It might be interesting, as subject of a further study, to find other patterns where this network of objects can offer new insight. What comes to my mind is the devotion to St Francis of Assisi throughout Italy, not just his images and reproduction, but his cross. The cross of Assisi, in Italian culture, plays a specific role in devoted people’s life. People recognise it from its singular shape, and it generates a sentiment of connection to the Saint, the town of Assisi (which they might have pilgrimages too) and the people that own it. Therefore, the network of objects that Professor Hempton identifies in Devotional Latin America and Chicago, might be also applied in modern day Italy to reveal nuances of this phenomena.

However, these shrines, images, reproductions, and crosses have the potential to transcend space and time because of the meaning that is behind the object itself. And the meaning, historically, we see has changed. I wonder how this would fit in the networking system that Professor Hempton developed, whether it could consist of the network itself, or rather being the nucleus that allow this objects to acquire their connective potential.

To conclude, as an undergraduate, Professor Hempton lectures on Networks, Nodes, and Nuclei in the History of Christianity are a precious source worth to keep in mind for the rest of my studies and a challenge for my young academic mind. The method of looking at historical events as a series of networks, each one with its own nodes and nuclei brings attention to analysis the events per se and noticing nuances that were hidden before. I am looking forward to see where Professor Hempton’s networks will take us in the lectures to come.

Lecture 3 Video

I’ve really been into my faith these past few years specially when the Pandemic hit us. I’ve been reading Christian books for men by Keion Henderson, https://www.keionhenderson.com/books/, reading historical blogs like this on the Christian faith, and really just attending Mass too. It really helps to know the history of our faith along with understanding the scriptures.