Lecture One: Who Are We? Belief, Evolution, and Our Place in the World

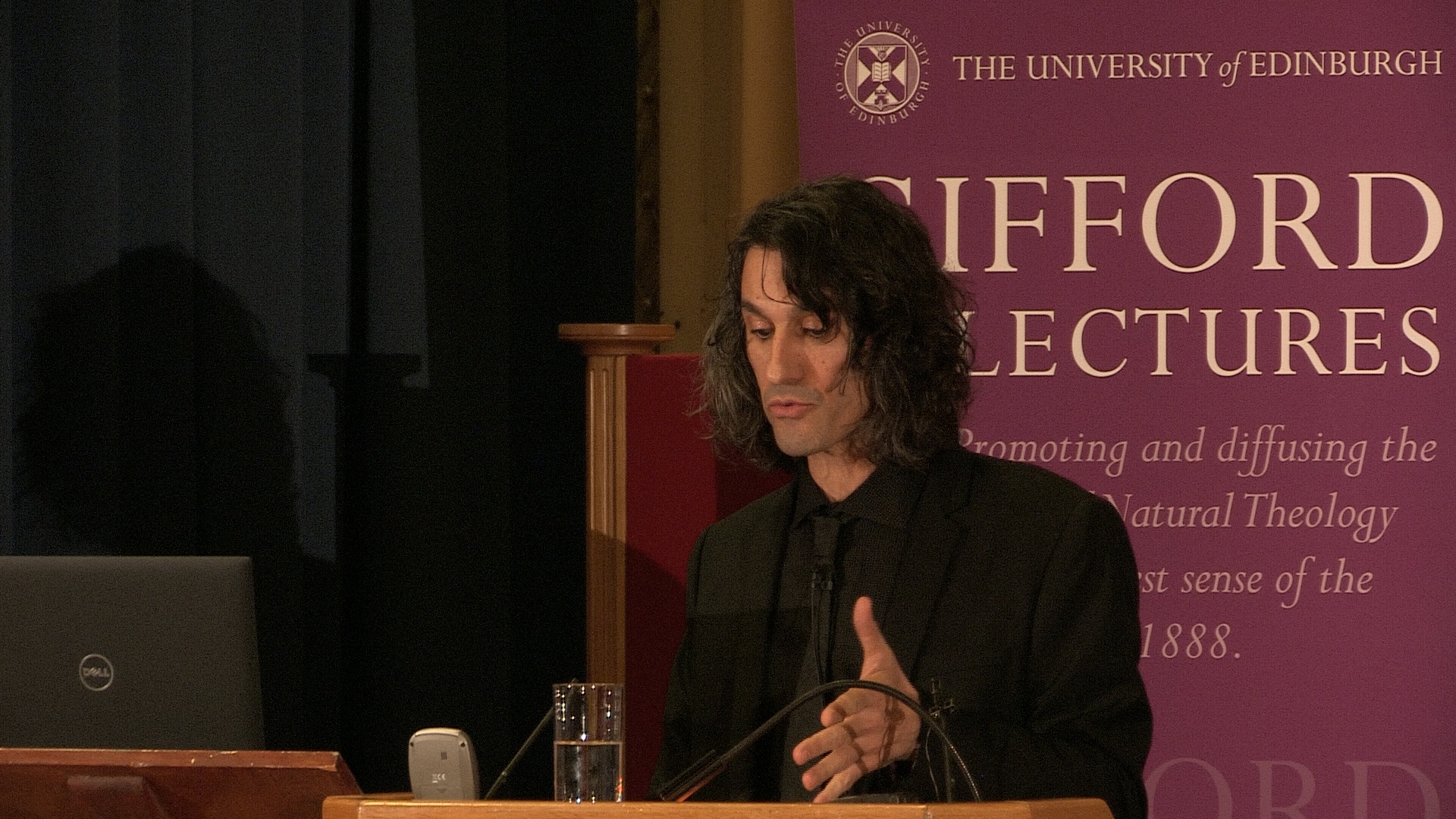

In this first lecture Professor Agustin Fuentes set the stage for the next five to come. The video of Fuentes’ lecture is embedded below for those who were unable to attend in person, or for those who’d like to listen to it again. An audio only version can also be found at the end of this post. In order to further facilitate discussion my colleague Jaime Wright will be adding her initial reflections on Professor Fuentes’ first Gifford Lecture. Wright is currently a PhD candidate at New College, University of Edinburgh. We’d like to reiterate that we warmly welcome anyone wishing to engage with Fuentes’ lectures to contribute their comments and questions below.

Professor Fuentes started off his first lecture earlier this evening by beginning to clarify what he does and does not mean by “belief.” For Fuentes the concept and phenomenon of human believing is more rich, dynamic, and holistic than it is often taken to be. As he stated, “belief is the human capacity to imagine, to be creative, to hope and dream, to infuse the world with meanings, and to cast our aspirations far and wide, limited neither by personal experience nor material reality.” In this sense one can see that belief, for Fuentes, is not merely concerned with assenting to what is, but it is also a way of intentionally existing toward what could be. As he went on to state, “Believing is a commitment, an investment, a devotion to possibilities,” and that beliefs are embedded, embodied, and enacted by human agents in evolutionary processes. Belief (both the capacity for and the specifics of) play a central role in normatively guiding our being in the world with, for, and against one another. This being the case Fuentes asserted that “belief is the most prominent, promising, and dangerous capacity of humanity.

Fuentes then moved on to relate his Gifford Lectures to the previous Edinburgh Gifford lecturer and Nobel laureate Sir Charles Scott Sherrington (1857-1952) concerning an explanation of human development that is “’neither accident nor miracle.’” As Fuentes stated, “It is this explanation, not just of human development, but of human becoming, of human believing, that we gather here eighty years on to tackle.” Fuentes pointed out that since Sherrington’s time we have made advancements in both our “understanding of the scientific process of development” and in our “study of the human” in both archeology and anthropology. These advancements in both the biological and the social sciences put us in a position to better appreciate the complexity and nuance of “what it means to ask how we become who we are.” It is as both an evolutionary scientist (concerned with “quantifiable origins, functions and process that undergird the capacity for belief”) and as a social scientist (concerned “to place the scientific knowledge in a context of engagement with the human experience, our social structures, belief systems, and daily lives”) that Fuentes aims in these lectures “to develop a better understanding of human becoming past, present, and future.”

Fuentes moved on to further articulate his understanding of belief by differentiating it from common dictionary definitions and popular antagonistic conceptions related to naïve deception. He positively related his understanding of belief with the literary theorist Terry Eagleton’s use of Kierkegaard in his 2010 Gifford lecture (also delivered here at the University of Edinburgh) highlighting that “the act of believing is an act of being wholly and completely in love with a concept, an experience, a knowledge.” He moved on to reiterate believing’s close relationship with hope and with the possibility of it being related to both “fearing unknown but fully felt” entities or perceptions and to “a certainty that cannot be seen, grasped, or measured.”

Fuentes then made an important distinction for his lectures between the capacity to have faith and the having of a specific faith, the former of which “arises from our core ability to believe.” In these lectures Fuentes is most concerned to further articulate the significance of this human “core ability to believe” rather than on the specific intentional contents, objects, and/or subjects that are believed in. In this sense he is mostly concerned to articulate the act or disposition of believing rather than the specific contents of belief (the latter of which are better tackled by philosophers and theologians). As he stated, “I seek to illustrate that the available evidence for how humans evolved and the myriad ways in which we experience, engage, shape and are shaped by the world, and one another, gives us substantial answers for why we have the capacity to believe and how we humans rely on that capacity as a cornerstone of the human experience.”

Fuentes then proposed four key questions to help us to better understand why we believe (which he will tackle throughout the lecture series):

- Who are we relative to the rest of the world?

- What key events and behaviors make us human?

- How did we change the world enabling the infrastructure for contemporary belief?

- How do we believe? (what are the processes by which we believe)

In combining these four questions Fuentes asserted that we can come to an evolutionary answer for why we humans believe. This led him to ask a further question: does belief still matter in the 21st century?

In beginning to tackle these questions Fuentes asserted that “there are three things we know about who we are biologically:”

- Humans represent an infinitesimally small percentage of all the life on this planet

- Humans are linked to all other life more deeply and substantially than most people think

- Despite being one small part of the great diversity of life, humans have become the most significant force affecting all other life on this planet

In light of this Fuentes stated that “how we became so significant on this planet is among the most important questions facing humanity.” Fuentes then went on to briefly describe and place the humans in relationship to the vast biological diversity with the more than 2 million species of life catalogued and with the lineage of backboned organisms in particular. After speaking briefly about the role of DNA and what it can and cannot tell us about who we are and where we have come from Fuentes stated that “the first part of the answer to who we are is that, biologically, we humans are squarely in the midst of the order of mammals we call ‘The Primates.’”

This led Fuentes to ask a further question: “What does it mean to be a primate?” After describing aspects of his research on primates Fuentes pointed out that it is “primate sociality” that “forms a key part of the basis for our capacity to believe.” He then went on to describe the complex nature of primate sociality (with its marks of behavioral innovation and flexibility) in further detail and differentiated it from other forms of sociality found in other species. As he later stated, “the capacities inherent in primate bodies and minds enable the emergence of particular possibilities for a diverse range of relationships between individuals” and, Fuentes added, these primate relationships are not restricted to those who are genetically related. Fuentes then went on to assert that the “human capacities for cooperation, collaboration, and for deep belief in, and reliance on, others are rooted in our histories as primates.” This, however, was not all that Fuentes wanted to draw from our understanding of primates. He suggested that the “possibilities of primates having an aesthetic sense, and the experience of awe” could offer us further insight into who we are and why we believe. He then went on to describe some of his and others’ experience of observing primates in the field (specifically with the aid of innovative “critter-cam” technology) and potential instances of primates exhibiting some sort of aesthetic sense and experience of awe.

Our primate history does help us understand “a critical aspect” of who we are, but it does not give us the whole story. As he stated, “the human story is not just the primate story.” At this point in Fuentes’ lecture he turned to a very brief overview of hominin evolution, still asking “what can they tell us about who we are?” Fuentes noted that the transition from “habitually quadrupedal movement” to “habitually bipedal movement” was of critical significance for how our lineage developed and interacted with the world and with one another. As he stated, “this morphology enabled our ancestors to move in new ways, to carry more items from one spot to another and to experiment with new manipulations of the world, and each other, combining hands, eyes and minds in ways that were novel and trailblazing.” He then went on to briefly describe a number of the earliest hominins and suggested that they all displayed relevant insights for understanding who we are and why we believe. One important aspect highlighted was their persistence despite being “favored food items for an array of larger predators.”

Fuentes then went on to spend some time focusing specifically on the Australopithecines and their significance for helping us better understand our lineage and “why that matters for developing a robust answer to why we believe.” He highlighted the development of collaboration and bonding in the face of intense danger that was uncommon even among primates and he also highlighted the developing interaction with stones and toolmaking. As he stated, “our deep ancestors developed the ability to see in stones the potential of a tool and to actively re-shape rock, a substance more solid than most, into new forms for their benefit. To this day that is a feat no other form of life on the planet, aside from our lineage, has ever mastered.”

As he stated toward the end of his first lecture, despite whatever similarities we share with other primates and hominins “we are the strangest primate and the strangest hominin” and so he ended his lecture by pointing toward a beginning. The beginning of the human niche and the human capacity for belief. As he elegantly put it:

Approximately two million years ago our direct ancestors endeavored to succeed in a landscape replete with a multitude of large predators and a myriad of competitors for food and shelter. What did a cluster of medium-sized, hairless, fangless, hornless, clawless hominins armed with a few rocks and some sticks have? They had each other and the glimmering of a new way to be in the world, a reality in which belief becomes a central force.

With that we look forward to what Fuentes has to tell us in the remaining five lectures. The first lecture opens up many avenues for questioning and has laid the groundwork for concepts promised to be developed further in the later lectures. Jaime Wright will offer her initial reflections to get the conversation started.

I would first like to thank Professor Agustín Fuentes for an excellent opening lecture on ‘Who are we? Belief, evolution, and our place in the world’. As a doctoral student who approaches the science-and-religion dialogue from what might be (loosely!) considered an anthropological and social scientific perspective, I am delighted to have Professor Fuentes as this year’s Gifford lecturer.

I am very aware that one of the challenges of responding to the first lecture of a six-lecture series is that Professor Fuentes will likely address many early questions or critiques over the next two weeks of his time with us. Furthermore, while Fuentes presented a clear and exciting overview to humanity’s hominin lineage as the core substance for the first lecture (and it is a necessary grounding, indeed) and whetted our attention to, for example, the possibilities of an aesthetic awareness in macaque monkeys (of which I hope to hear more), it is Fuentes’ general introduction to which I wish to return for discussion.

Being a diligent scholar, Fuentes took time to explain how he will be using the term ‘belief’ in his lectures. Fuentes claims that he is interested in explaining human becoming, which he connects with human believing—or more specifically, the distinctive human capacity for belief. According to Fuentes this capacity is constituted by meaning making, imagination, and hope. (I look forward to hearing these connections unpacked in upcoming lectures.)

During the question and answer session, an individual asked Professor Fuentes to distinguish between belief and imagination, likely referring to Fuentes’s previous work The Creative Spark: How Imagination Made Humans Exceptional and other publications. Fuentes pointed out (as he had stated in his lecture) that he defines belief as something more than imagination. Recalling this question, I wish to pose a similar question: what is Fuentes’s definitional distinction between belief and faith?

In seeking to define belief, Fuentes related belief to the term ‘faith’. Fuentes claimed that he is ‘separating the having of faith in a specific set of beliefs from the capacity to have faith, which arises from our core ability to believe’. I understand from this that Fuentes distinguishes between belief and faith; however, Fuentes does not elaborate upon what he means by faith. Rather, he then explains that he will stop short of any particular faith dialogue, leaving that to the faithful, the theologians, and the philosophers.

I have hope that Fuentes has a ready answer concerning his understanding of faith and its connection to belief, for despite acknowledging that he is neither a philosopher nor a theologian, Fuentes hints that he is not afraid of transgressing categories of academic departments in a pursuit of inter-disciplinary work. Indeed, although presenting an evolutionary narrative in his opening lecture, he also suggested that he will (throughout the lecture series) be presenting an evolutionary narrative that specifically ties the explanation of humanity to our distinctive capacity for belief. This seems to be a proposal of an integration of the narratives of evolution, philosophy, and theology—a goal of natural theology. But to stop at belief seems to be to stop just prior to engaging theology.

Considering the vague distinction between belief and faith, I find myself left thinking that perhaps (echoing Fuentes’ brief answer to the relation of imagination to belief) faith is to be simply understood as something more than belief. But this understanding of faith, from a theological perspective, seems overly parasitic upon belief, which still seems parasitic upon the concepts of imagination, meaning making, and hope (which also remain undefined at this point in the lecture series, though Fuentes has written about these concepts before). While I understand and appreciate Fuentes’ self-imposed limitation before theologians and philosophers when it comes to discussing faith, I still think that an elaboration of Fuentes’ understanding of faith, and therefore his distinction between faith and belief, would be a helpful elucidation to make at the outset of this lecture series dedicated to natural theology.

Why might this definition or distinction matter? Let me give you an example from my own experience, listening to Fuentes’ introduction to the entire lecture series. When Fuentes outlined the various questions he wishes to address in the series, he provided a final question for consideration: ‘today in the 21st century does belief matter?’ I must admit I found this question duller than Fuentes perhaps intends, thinking to myself ‘obviously, yes’. I found I would rather ask (or rather know the answer to the question): today in the 21st century does ‘religious’ belief matter? Or perhaps in the 21st century does ‘faith’ matter? These seem more pressing questions, for it is not simply belief in the 21st century that I find intriguing, but more specifically religious belief or faith in the 21st century, a time when naturalistic or reductionistic evolutionary narratives abound.

Looking at the abstracts of lectures to come, I suspect that Fuentes will deal with this issue in his fifth lecture: ‘Why do we believe? A human imagination and the emergence of belief systems’. I hope that he will, in that lecture, bring together imagination, belief, and faith (in the form of belief systems, perhaps?—but distinctions between faith, belief system, and religion also exist). However, I continue to think that an explanation of the relation between ‘belief’ and ‘faith’, similar to the need for an explanation of the relation between ‘imagination’ and ‘belief’, would be helpful from the outset of Fuentes’ lectures—for it is the hints at theology, that something beyond belief that might be termed ‘faith’ by Fuentes, that keep me coming to these prestigious Gifford lectures.

Superb introduction. Impressions that come to my mind include belief as meaning created as illusion in the perpetuation of our species. I found it interesting that “Truth” was not mentioned anywhere as the goal of belief and knowledge. I am intrigued by the anecdotal story of the 17 hominins dying to protect each other, as Prof Brown commented on their mutual sacrifice. I am also fascinated that primates may share our appreciation of beauty. To re-iterate, excellent lecture and I am looking forward to the coming talks. Thank you Professor Fuentes.