Cornel West Lecture 3: Folly Presto

Lecture Three of this year’s Gifford Lecture Series took place on Thursday 9th May at the Informatics Forum, and was chaired by Professor Sarah Prescott, Professor of English Literature and Vice-Principal and Head of the College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences.

You can watch the Lecture recording on YouTube, and join in the discussion by leaving a comment at the bottom of this page.

Below is a summary of Lecture 3, Folly Presto, and a response by PhD student in Creative Writing, Lexie Angelo:

Over the course of the Gifford Lectures thus far, Dr West has drawn on the works of a range of philosophical, literary, and theological figures, towards a definition of what he calls a ‘jazz-soaked philosophy’. To be sure, this invocation of various influences – often, as he remarks, in conflict with one another – is testament to the praxis of a polyvocal and polyrhythmic voice that the jazz tradition evokes. What brings these thinkers together is their attention towards the catastrophic, their revelations that the way up and the way down are interlinked, and, as this lecture considered, their ability to mobilise the catastrophic through the tragicomic, to enact what sceptics might term ‘folly’ and ‘foolishness’ in their refusal to be subsumed into regimes of hierarchy and oppression. Might folly offer the path to shifting our attention, paideia, towards the catastrophes we encounter (and perhaps enact) everyday? Can foolishness be a means of achieving a topos, the state of being unsubsumable, of a life that resists category?

Portrait of Erasmus, by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1523

As in his previous Gifford Lectures, Dr West opened by noting that his events are alive with Kairos, with moments of connection between the companions and thinkers in attendance. These moments of recognition continue the centring of piety modelled by Erasmus, the focal figure of this lecture, in whom we can locate an example of the jazz-soaked philosophy’s impetus to be not only humble and patient, but so too open-minded, empathetic with others, and able to understand their perspective of and position in the world.

Reviving some of the ideas that have emerged in the previous lectures, Philosophic Prelude and Metaphilosophic Andante, West reminded us of Thomas More’s questioning of why Socrates never cried, and Jesus never laughed. Noting that Socrates is in fact described as laughing in Phaido (even if he never wept), West argued that we have an underdeveloped sense of the comic, but none of the tragic in his work. In contrast, the jazz-soaked philosophy ‘connects the catastrophic with the tragicomic’ and opens up a way of looking at philosophical traditions wherever they might emerge from, in order ‘that you conceive of yourself in regard to your humanity, in the form of, first and foremost, parrhesia’.

Parrhesia, West explained, reflects what we might call plain or unintimidated speech; that which Foucault named ‘fearless’ speech, Socrates recognised as the cause of his unpopularity and the reason he was put to death. Crucially, however, West argued that we cannot simplify parrhesia into the contemporary, libertarian notion of free speech; rather, it encompasses freedom as what emerges from the ‘depth of your heart, especially at a moment of catastrophe which defines who you fundamentally are in terms of your quest for integrity, honesty, decency, and sense of character’. Quoting Thomas Paine’s claim that certain times test us and allow us to find out who we really are, West argued that such moments of catastrophe are where paideia ‘kicks in strong or goes limp’; it is where we cultivate a critical discernment and maturation that connects the ethics of conviction with the ethics of responsibility.

Reflecting on his reading of some of the canonical works in philosophy and theology, naming Sophocles, Antigone, Euripides, Augustan, Aquinas, and Dante, Dr West commented that those texts that have unsettled and shaped Western thinking are nonetheless riddled with forms of injustice and hierarchy, and at the same time reflect a hugely underdeveloped sensibility towards the comic and the tragicomic. Perhaps, he continued, this reflects a common desire to evade the catastrophic – or, alternatively, that those who do contend with catastrophe fear misanthropy, the cynicism of humanity’s history, described by Hume as a march of ‘madness’, ‘imbecility’, and ‘wickedness’. The counter to this cynicism is exemplified most potently in the blues, through which, West discussed, African American peoples have wrestled against the forces of American Empire, have ‘engaged in forms of truth telling and justice seeking’ that are not merely a mode of politics, but a vitally existential conception of what it means to be human and among humans.

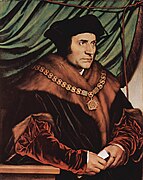

Portrait of Thomas More by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1527

So too does Erasmus, West posited, begin with love. Noting that his In Praise of Folly begins with an epistle to Thomas More (and indeed its Latin title Moriae Encomium plays on the pun ‘In praise of More’), he claimed that Erasmus’ work is indicative of a deep friendship and model of love, philia – the same invocation of dedication and friendship that begins each of his lectures. Such love connections are, he continued, profoundly jazz-like, offering a means of sustaining the self when confronted with overwhelming crises; of connecting love to laughter, and using folly and foolishness to imagine modes of being and futurity that offer a life beyond that which we occupy now. This is a praxis of thinking and feeling and being manifest in the Black tradition – and the lives of those who, even if they have never read the works of Heidegger, Foucault, or C. L. R. James, have nonetheless known suffering, and whose ability to endure collapses the ‘so-called worldly wisdom’ that dehumanises, oppresses, and exploits them.

To resist is to ‘say and do and act foolish in the eye of the world’ as one calls into question the structures of feeling and thought taken as authoritative. Through the nexus of love and folly we enact empathy and imagination – ideas that, per Montaigne, allow one to take seriously paideia, to be educated in the lived experience of others – and it is at this juncture that we find Erasmus’ own jazz-soaked ideas.

In the spirit of a dialectical attention towards the best and worst, the benevolence and the evil, manifest in all of our structures, institutions, and indeed ourselves, Dr West considered Erasmus’ own inability to come to terms with various catastrophes and crises wrought upon Jewish, Muslim, and indigenous peoples, across the New and the Old Worlds. Nonetheless, each of these violent realities have come not only to ‘haunt’ Europe, but to question the very foundations of its claims to authority. It is W. E. B. Du Bois, West continued, who shows us that these catastrophes imposed in Europe are the same as those visited upon Africans; we need the synoptic vision and polyphonic voicing of the jazz tradition to recognise how these parts exist in continuum. Beyond the Socratic, dialogic, model of speech, jazz-soaked philosophy helps us to consider the many voices inside each of us: not only the voices that influence our thinking, but the very contradictions, incongruities, Whitmanian multitudes that are the measure of the complexity of any single being. These are the source of humility and maturity, the traits necessary in our wrestling with the catastrophic.

jazz-soaked philosophy helps us to consider the many voices inside each of us: not only the voices that influence our thinking, but the very contradictions, incongruities, Whitmanian multitudes that are the measure of the complexity of any single being

Reflecting on a moment of self-parody in Erasmus’ In Praise of Folly, West quoted an excerpt from the text comparing the ‘lot of a wise man’ and a ‘clown’: ‘Give me any instance then of a man as wise as you can fancy him possible to be, that has spent all his younger years in poring upon books, and trudging after learning, in the pursuit whereof he squanders away the pleasantest time of his life in watching, sweat, and fasting; and in his latter days he never tastes one mouthful of delight, but is always stingy, poor, dejected, melancholy, burthensome to himself, and unwelcome to others, pale, lean, thin-jawed, sickly, contracting by his sedentariness such hurtful distempers as bring him to an untimely death, like roses plucked before they shatter.’[1] What Erasmus reveals in such lines, West argued, is the ‘courage to laugh at yourself, to connect it to the tenacity of purpose’.

Charles Mingus

This courage is crucial to the comic genius of jazz, equally demonstrated in the bass performances of Charles Mingus, who showed humility in his framing of himself as ‘Beneath the Underdog’, but still used his music to draw attention to American racism, including the ‘Red Summer’ of 1919 – a confluence between the explosion of antiblack violence and lynchings in the U.S., and Weber’s previously noted essays of the same year on the end of the Age of Europe. This music is, per West, parrhesia in action, and marks a profound commitment to arete, excellence and virtuosity; such craft works not simply to delight the audience, but to move them on a visceral level, to recall the memory of ‘those who have gone into the shaping of them, and give a sense of connecting them to the loved ones who come after’. The lines of Mingus and the lines of Erasmus equally offer paiedeia as a liberation, a salvation; in refusing abstraction they implore us to ask what it means to be a living, feeling, being person, and thus ‘drip with blood and sweat and tears’.

What Erasmus’ writings do, West developed, is to accent orality. So too with a jazz-soaked philosophy: orality is paramount in its centring of eloquence, an ethos towards speaking well, acting well, and writing well in tandem. Orality, so infused with music, mobilises ‘the best of us wherever we are’, encouraging what West named a heartfelt self-emptying, a kenosis, through which we touch people deeply, and engage in a turning of the soul, of the paeideia Plato called for in the Republic. This transformation, this Christian practice of metanoia, West developed, is a pillar of the Black church tradition, evidenced in the orality of figures like Gardner Taylor, Prathia Hall Wynn, Sandy F. Ray, Manuel L. Scott, Sr., and C. L. Franklin – those who, he described, unite a Cicerian with an African tradition, who enact ‘oral power with vibration in their language and hearts and minds’, who give their audiences hope through catastrophe. ‘You cut those sentences and they bleed […] because there [are] human beings’ in them; to recognise those who bleed like us, like those in Gaza today, West argued, is to find moral connection on the deepest level.

Marginalia in In Praise of Folly

Through Erasmus, he argued, we see how the jazz-soaked philosophy, as a way of being in the world, begins with self-parody, with critique, in order to transform it into ethical conviction and action. Certainly, this is seen in Erasmus’ notes on philosophers, which West quoted at length: ‘Next to these come the philosophers in their long beards and short cloaks, who esteem themselves the only favourites of wisdom, and look upon the rest of mankind as the dirt and rubbish of the creation: yet these men’s happiness is only a frantic craziness of brain; they build castles in the air, and infinite worlds in a vacuum. […] But though they are ignorant of the artificial contexture of the least insect, they vaunt however, and brag that they know all things, when indeed they are unable to construe the mechanism of their own body: […] But they then most despise the low grovelling vulgar’. While we might be tempted to read this as a mere condemnation, West put forward that Erasmus distinctively allows folly to ‘speak about herself, engage a praise of herself in a public oration’. Erasmus’ reflections on philosophy evoke the contradiction of Demosthenes’ authority as a speaker and his cowardice in battle, further exemplifying the incongruity at the heart of all people, while making the claim for action in order to counter mere sentimentality or cynicism. Erasmus, per West, uses this model of irony to transform; in this way it is akin to Kierkegaard’s generative irony, one that demands action, love, and justice.

King Lear and the Fool in the Storm, by William Dyce, 1851

This is the same work, West concluded, of a jazz-soaked philosophy: such a praxis depends upon enhancing the voices of others, constituting a polyphonic voice that touches the lives of its audience, and brings into conversation beings past, present, and future in recognition of collective struggle and collective action. Foreshadowing the end of In Praise of Folly, to be continued in the next lecture, West noted Erasmus’ reading of Paul in the New Testament, and the notion that the gospel, and Jesus himself, are folly in the eyes of the world. Seen through a ‘Christian humanist lens’, infused by the discourse of the classics, Erasmus begins with love, before finding a union of levitas, laughter, and gravitas, life and death. Such blending of the ecstatic and the mad imagines later connections to timeless characters written by Cervantes, by Shakespeare, because these are the touchstones we all return to in our wrestling with humanity, West closed. It is with this attention to our plurality – our connections with others, and our own internal incongruities – that we recognise everyone as ‘cracked vessels with a sense of possibility’, of redemption, and through which we can constitute actions and deeds that might move us through our catastrophic realities.

[1] I have quoted from a different edition of In Praise of Folly to the one Dr West used in his lecture, so there may some minor variations in language between this summary and the lecture. Quotations used here are taken from the edition available via Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/30201/30201-h/30201-h.htm

Response by Lexie Angelo:

Shape-shifting: Catastrophe, self-love and jazz

“I wish I knew how it would feel to be free, I wish I could break all the chains holding me”- Nina Simone, I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free, Track 6 on Silk & Soul

Catastrophe is always there. Reinventing itself, plotting, shape-shifting—waiting in the wings of the largest of political arenas, flashpoints and cultural protests, all the way down to the smallest of living rooms, lecture halls and kitchen tables. Unsettlement. Disruption. Upheaval. Tragedy. Helplessness. Each one, a branch on the trunk of the catastrophic. As Dr Cornel West orates in his third lecture, Folly Presto, “catastrophe is not new” and rather than be seduced by its incomplete history, he offers this suggestion: hold on to the jagged edge of truth.

But catastrophe is an intoxicating seducer—an omnipresent and even omniscient narrator. History after all, is notorious for repeating itself. How does one reconcile catastrophe in life and in art? West’s lecture connects Erasmus’ In Praise of Folly to jazz music which led me back to Toni Morrison (an author West promises to discuss in Lecture 6) – and in particular her novel, Jazz, and how North American writers can reconcile the practices of European colonialism through The Gothic as a literary mode [2].

A mural in Harlem

In Jazz, fifty-year old Violet is unsettled by ‘the City’ and further burdened by the traumas of infertility, her mother’s suicide, and her husband’s infidelity. In reading Jazz, I harness the theme of constant migration and resettlement experienced by Violet into my own research in the postcolonial gothic. Tom Hillard [4] suggests that settled environments “evoke fear” as they “persistently feel unhomely and foreign to the settler” despite the settler being home. The postcolonial gothic is linked to this sense of unsettlement, as well as to the environment [2] the legacy of imperialism, and countries with occluded histories as a result of colonialism, and in this way draws parallels with West’s conception of the catastrophic [7]. In Jazz, ‘the City’ is a place of disorientation, and Violet is pulled this way and that, unable to find her footing in Harlem, a setting conceived by Morrison to be purposefully unstructured and improvised like jazz music, “Round and round about the town. That’s the way the City spins you” [5].

For Violet, the jagged edge of truth slips in and out of reach. She grapples with forgiveness, maternal lineage, regret, and defining herself while at the same time defining what it means to be black in Harlem and America [6]. In fiction, catastrophe (in any form) is the setup to the question: what is at stake? Not only for the characters, but for the world itself.

Laughter and writing as a cracked vessel

The craft of literary writing, including the production and revision of an imagined construct in the form of a novel, like any other artistic pursuit requires the acceptance of failure and humility from the artist. “The polyphonic generates humility,” West states, illuminating how the act of creating, improvising and performing of jazz, requires the voices and contributions of others, including the many voices inhibited within the artist themself. The artist, performer, or writer can be considered what West describes as a “cracked vessel, like anyone else,” in other words, an imperfect creator fraught with their inherited histories, internalized beliefs, values, and ethics. Catastrophe exerts itself on the artist-as-vessel, provoking parrhesia—what West refers to as “speech that comes through your heart” even though it may come at personal risk.

Toni Morrison

To say something of substance, the writer, the jazz-soaked philosopher, shoulders the responsibility of their words, choosing to engage in any acts of candidness, frankness and truthfulness. Morrison’s Jazz exposes racial violence, injustice, poverty and the stress factors of migration. She goes straight to the heart of what is at stake in a never-ending cycle of tragedy. How does one person, let alone an entire community, recover and move on from generational and cultural trauma? From slavery? From displacement? In the spirit of polyvocality, Morrison and West together offer an answer: the unreasonable optimism of jazz. Improvisation, originality and change—these are the trademarks of both jazz music and the ways in which a community heals and recovers from the catastrophic. As West says, “speaking well, writing well, and acting well are all tied together.”

Violet’s recovery technique through the catastrophic is laughter. As Erasmus states In Praise of Folly, “we should sink without rescue into misery and despair, if we were not buoyed up and supported by self-love” [1]. Morrison also uses laughter as a recovery method in her novel Beloved, which is to “face your fear, acknowledge your past, and move on” [3]. Laughter becomes a pathway towards healing, as Violet realizes that “laughter is serious. More complicated, more serious than tears” [5]. West echoes Morrison’s words, stating that “love connections is very jazz-like” and jazz music is linked to laughter. The courage to laugh at one’s actions, as Violet does, embodies the humility which West says “can turn the soul.”

Cited Work

[1] Erasmus, In praise of folly / Erasmus. New York: Open Road Media, 2016.

[2] S. Groeneveld, “Unsettling the Environment: The Violence of Language in Angela Rawlings’ Wide Slumber for Lepidopterists,” Ariel, vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 137–158, Oct. 2013, doi: 10.1353/ari.2013.0034.

[3] T. E. Higgins, Religiosity, Cosmology and Folklore: The African Influence in the Novels of Toni Morrison, 1st ed. in Studies in African American History and Culture. London: Taylor and Francis, 2014.

[4] T. J. Hillard, “‘Deep Into That Darkness Peering’: An Essay on Gothic Nature,” Interdisciplinary studies in literature and environment, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 685–695, 2009.

[5] Toni. Morrison, Jazz / Toni Morrison. London: Chatto & Windus, 1992.

[6] A.-M. Paquet-Deyris, “Toni Morrison’s Jazz and the city: Document View,” African American review, vol. 35, no. 2, pp. 219-, 2001.

[7] C. Sugars and G. Turcotte, Unsettled Remains: Canadian Literature and the Postcolonial Gothic. Waterloo, ON, CANADA: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2009. Accessed: Mar. 07, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ucalgary-ebooks/detail.action?docID=685924

Recent comments