Cornel West Lecture 2: Metaphilosophic Andante

Lecture Two: Metaphilosophic Andante, took place at St Cecilia’s Hall on Tuesday 7 May, and was chaired by Professor Mona Siddiqui, Professor of Islamic and Interreligious Studies, Assistant Principal Religion and Society, University of Edinburgh, and Jane and Aatos Erkko Chair, Helsinki Collegium.

You can watch the Lecture recording on YouTube, and join in the discussion by leaving a comment at the bottom of this page.

Below is a lecture summary, and a response by PhD student in Philosophy Tony Baugh.

Dr West opened his lecture by resuming from the conclusion of his previous lecture, Philosophic Prelude, where he closed with remarks by Max Weber upon the concurrent collapse of the Russian, the Austro-Hungarian, and the Ottoman Empires in the late 1910s. This moment, West reminded us, marked the end of the Age of Europe, and with it a belief in the possibility of a united, transnational project, leading the way for the Age of America we now occupy.

Billie Holiday

While the words of Weber at a time of overwhelming catastrophe help us to think through the compounding crises of our own era, Dr West potently interjected that in the spirit of the jazz tradition, we can never talk about an isolated voice as the mark of authority (even to talk about John Coltrane, he noted, is to also talk about Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Sarah Vaughn, Dinah Washington, Billie Holiday, among others). Rather, jazz teaches us about the value of a ‘collective voicing’, which in turn might enable us to recognise the mutual imbrication of all our actions and institutions.

Noting that in 1919, the same year of Weber’s essay, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) promoted the hymn ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing’ as the Black National Anthem, Dr West showed how a jazz-influenced emphasis on polyphony implores us to consider these events in relation. Indeed, the NAACP’s use of song as a morally, spiritually, and artistically rich response to the traumas of American racism and the violence of lynching, reflects in his view the potency of voice as a force to struggle for, a means of articulating a refusal to conform to a system that harms. ‘Sometimes the bars on the page remind you of bars on the jail’, he commented, ‘in your mind, in your heart, in your soul, in your structures, in your institutions – Lift Every Voice is both indistinctively individual but inescapably collective.’

Sometimes the bars on the page remind you of bars on the jail’ […] ‘in your mind, in your heart, in your soul, in your structures, in your institutions – Lift Every Voice is both indistinctively individual but inescapably collective.

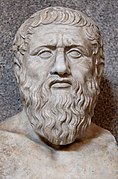

It’s here that Dr West turned to what he names the inauguration of philosophy in the West through the writings of Plato – and in the style of his jazz-soaked philosophy, he infused his reflections on Plato’s responses to catastrophe with a roster of other literary and philosophical figures whose works variously reflect the redemptive capacity of music, art, and philosophy.

His lecture’s call and response chorus began by turning to Joseph Conrad, whose 1899 novel Heart of Darkness marks a jazz-like sensibility in its attention to the catastrophic crimes of European empire even as it tries to ‘stay in contact with the best of it’; nonetheless, drawing on Chinua Achebe, Dr West remarked that by not hearing the voices of the colonised Africans, Conrad’s attempt remains flawed in its singular perspective.

Next came James Joyce, whose 1907 short story ‘The Dead’ evoked the perspective of a colonised people. Noting that Joyce had already published chamber music, Dr West suggested that his evocation of the catastrophic arises in the story’s grappling with one’s inability to love. This emphasis on the struggle for love, the attention to pain, reveals a crucial difference from much of our philosophic heritage. Noting that Socrates ‘never cries, never sheds a tear’, his influence marks an absence of feeling and a ‘blindness at the pillar of western civilisation’, because ‘anyone who’s never shed a tear has never loved anybody’. The jazz tradition, crucially, begins with tears and the cries of the oppressed, and transfigures that pain into a voice for good; so too must a jazz-soaked philosophy.

Franz Kafka

Dr West marked this ethical attention to suffering, as much as love, across further allusions: Kafka’s 1912 short story ‘Metamorphosis’, for instance, presages the decline of Europe’s empires, yet seeks to connect that catastrophe to life through feeling. Thomas Mann’s novella of the same year, Death In Venice, invokes the life of Gustav Mahler and his vocation to create beauty out of moments of oppression. Virginia Woolf’s 1917 short story ‘The Mark on the Wall’ in turn signifies a disruption in the quotidian order of things, and marks a shift in how we understand the world around us; this minor catastrophe opens possibilities against dogmatic thinking, and reveals the power to lift every voice against marginalisation.

Socrates, Dr West put forward, exemplifies topos, the state of being unclassifiable and unsubsumable, a level of complexity that cannot be quantified or contained in any singular school of thought. This too, he noted, is the quality of a ‘good jazz musician’, like the example of Ella Fitzgerald, who, per Duke Ellington, was a ‘wave in an ocean, so distinctive that there’s no conceptual net that can catch her richness’.

At the same time, Dr West remarked that Socrates was obedient to divine voices, even as he is remembered for his rigorous interrogation and intellect, as seen by his taking the call to practice music. His legacy is hence defined by what West named ambiguity and ambivalence; yet rather than suggesting weakness, these signify ‘the benchmark of spiritual maturity’, of ‘humility’, alongside the tenacity to ‘stand with courage’. Such traits are as essential in our own time of catastrophe, and are seen today among those fighting war and oppression globally; this moral conviction marks kenosis as a flow of love and compassion, the emptying of oneself towards others. These are qualities of the jazz tradition, which strives to ‘democratise a topos’ and a ‘voice’, and locates a capacity to make people beyond category.

Plato

Dr West next returned to Plato’s Republic (607B), which he named the scene of instruction and ‘emergence of philosophical discourse in the West’. Highlighting the text’s conflict between philosophy and poetry, West quoted: ‘Homer is the most poetic of poets and the first of tragedians, but we must know the truth, that we can admit no poetry into our city save only hymns to the gods and the praises of good men’, and argued that this reflects not a critique of poetry entire, but of mimetic poetry that makes claims to truth. What we see in the fight between philosophy and poetry, he put forward, is the fight over paideia, over forms of education.

Paideia is a concept that Dr West returned to throughout his lecture. Continuing his discussion of the vocation of philosophy in Lecture One, he argued that what is at stake in this notion of education is in turn invocation, the capacity for remembrance and the recognition of those influences that have informed one’s calling – the voices that shape and speak beside one’s own.

Reading further from the Republic, Dr West suggested that (like Socrates) Plato’s work bears a tension between a fear of poetry (its capacity to make ‘pleasure and pain […] lords of your city’) and his recognition of its distinct power to unsettle the forms of hierarchy that he inscribes in his conceptions of the soul and of society. Indeed, noting Plato’s distinctly poetic and democratic form of writing, West noted that Plato himself provides the critique of his own positions, and his work bears a polyphonic, jazz-infused model of internal struggle and incongruity – one that is reflected in all of us.

These struggles, of course, bear various examples in the history of philosophy. The discipline has, West noted, over the past sixty years been overtaken with metaphilosophy and mythologising, whereas what is needed in response to catastrophe is to ‘jump into the mess’ of language and of feeling in order to act. We see this, for instance, in the work of Heidegger, whose capacity to think deeply, is tarred by his affiliation with Nazism; as West summarised: ‘the love is not forthcoming’. Meanwhile one of the most potent critiques of this contradiction, this absence of kenosis, is seen in poetry, and the work of Paul Celan, who instead makes a claim for compassion. Indeed, as Dr West remarked, in the wake of catastrophe, can scepticism and philosophical melancholy be adequate to fortify ourselves? What do we do when reason is not enough?

Nina Simone

What Plato reveals in his own contradictions, Dr West continued, is the capacity to refuse compartmentalisation. His union of personal and political, social and spiritual marks a ‘synecdochic imagination’, a union of philosophy and poetry capable of attending to the complexity of what it is to be human. Grappling with concepts of ‘death, dogma, and domination’ Plato’s ‘fundamental vocation is to make the world safe for Socrates’, and it is this idea that informs Dr West’s own philosophic practice, his desire to, in his words, make the world safe for ‘what went into the West household, of pouring into me as a little Black child unbelievable levels of love and integrity and courage, and being open enough to learn from the voices of others, intellectually, theoretically, so I can be a wave in an ocean that can take me back to Martin Luther King, to Fanny Lou Hamer, to Curtis Mayfield, Nina Simone, John Coltrane, a whole host of others that are part of that flow’, to ‘be just a brief, brief creature in space and time by means of seeing and feeling and acting grounded in lenses, broader lenses, to view the world, deeper feelings, swings and grooves, polyrhythms, and then, most importantly, the actions, the deeds, the praxis’.

to be just a brief, brief creature in space and time by means of seeing and feeling and acting grounded in lenses, broader lenses, to view the world, deeper feelings, swings and grooves, polyrhythms, and then, most importantly, the actions, the deeds, the praxis

As Dr West closed his lecture, he remarked that this is what Plato teaches us: that the way down and the way up are intertwined, that we must begin with death and attention to those on the margins. The debate over paideia, seen from a blues perspective, invites us to contemplate the formation of attention, and the ways we attend to things that matter: life, death, love, and feeling against structures and institutions of hatred. The question that follows is how we might engage and mobilise that shift necessary to wake people up from the metaphoric cave at the centre of Plato’s text.

When Plato asks what courage means, Dr West concluded, we find the only instance of his phrase ‘musical life’. Courage in this view is a model of harmony between self and action, and from this all other virtues can take shape. The spiritual decay and catastrophe of our present age is the absence of courage both in our leaders and institutions, and in our everyday actions. A jazz-soaked philosophy asks us to mobilise the love, pain, and suffering, to transform it into a vocation and struggle through catastrophe.

Response by Tony Baugh:

“One of the great contributions of the Jazz tradition is to democratize ἄτοπος, to democratize the voice.” – Dr Cornel West, May 7, 2024

Huey P. Newton

On the daimon (δαίμων), that is, the voice transcendentally received and reckoned through subjectivation, like that of the inimitable force of music and poetry, brought into focus in the second of his Gifford Lectures entitled “Metaphilosophic Andante,” Cornel West posits that the Apollonic heroism of rugged individualism (of voice) has the propensity to lead to varying degrees of moral apathy in the demos (δῆμος). The timbre of this lecture underscored the limitations of metaphilosophy and exalted the anti-heroism of paideia (παιδείᾱ). Paideia, the praxis of learning to become a thinking, dialogical, well-integrated and contributing member of society at large, for West, is not a mere instrumentalist pursuit of the individual but is that mindful cultivation of self that beatifies the whole of the collective Gemeinschaft. In this way, West, who, while an undergraduate student at Harvard (1970-1973), assisted in the free breakfast programs orchestrated by the Black Panther Party (but never became a member of the Party because he is a self-avowed free loving Black Christian), reminisces the revolutionary sentiment of Huey P. Newton, Co-Founder of the Black Panthers in his essay “Black Capitalism Re-Analyzed I” (1971). In the work, Newton engages the concept of “the hero” by comparing him to the capitalist, disconnected and aloof, self-seeking and self-adorned in his importance, not necessarily morally bereft, but distanciated from the plight of the greater masses of people, the huddled masses yearning to breathe freely, yearning for justice. Newton writes:

“One of the primary characteristics of a revolutionary cultist is that he despises everyone who has not reached his level of consciousness, or the level of consciousness that he thinks he has reached, instead of acting to bring the people to that level. In that way the revolutionary cultist becomes divided from the people; he defects from the community. Instead of serving the people as a vanguard, he becomes a hero. Heroes engage in very courageous actions sometimes and they often make great sacrifices, including the supreme sacrifice, but they are still isolated from the people.”[1]

Ralph Waldo Emerson

West desires to break free of the individualist heroism that is claustral and insular and wants to rather adopt a modality of being in the world that is connected to the sufferings of others. One of the foremost and strident interlocutors in West’s work is Ralph Waldo Emerson, whose lectures on human culture, (“[…] treating successively higher states of the soul”, to be paired with his lectures “Heroism,” “Prudence,” and “The Over Soul”)[2], include “Holiness” (1838), in which he says the following:

“In the last Lecture I endeavored to illustrate the leading traits of the Heroic character; and defined it as a concentration and exaltation of the Individual, he setting himself in opposition to external evils and dangers, and regarding them as measures of his own greatness. It was said that the hero scorns the frivolous and sordid life of men around him, and delights in exhibiting by great action or passion the superior endowments of his own nature.”[3]

Pressing towards the mark of the higher calling of communalism against individualism, West invites us into the realm of the funky, of the external (and interior) proclivities of vices and virtue that is humanity. This is a liberatory move, informed by the Black American cultural tradition, that “[…] begins with the moans and groans and cries” of the community, in humility, as an act of kenosis (κένωσις), that is, the emptying out of oneself for the greater good of humanity, as one bearing the excruciation of the ignominy of the cross of Calvary, suffering while intonated with the suffering of others. This is the Jazz sensibility, through the lens of the catastrophic, that harmonizes through collective suffering the amalgamated beatification of the demos as one selfless and organized humanizing song. Therefore, when Dizzy Gillespie says that “[…] it is of prime interest and to one’s advantage to learn the keyboard of the piano […],” he presages a Westian conception of societal taxonomy, for while the trumpet may be pitched in Bb and the alto saxophone may be pitched in Eb, the piano pitched in C will ever be the innately fluid architectonic, unifying principle that engenders pragmatic cooperation of the bandstand of life. We find our voice, our daimon, in each other. Thus, when at the outset of this lecture, when West invokes the Black National Anthem “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” (1900) with lyrics by James Weldon Johnson and music by his younger brother John Rosamond Johnson, he reminds us that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was responsible for popularizing the song as a counter-terroristic move to engender the panoply of Americans to raise the alarum of their voices against becoming well-adjusted to injustice. Here, West articulates the intense necessity of humanity clinging to “the harmonies of Liberty” in response to rapidly contingent Western technocratic and oligopolistic society in relative moral and social decay.

When West begins his lecture, he brings with him to innervate the ebullience of his improvisation, a chordal landscape to foundationalize his flatted fifths,” his blue notes, Joseph Conrad (Heart of Darkness [1899]), James Joyce (“The Dead” [1914]), Franz Kafka (Metamorphosis [1915]), and Virginia Woolf (The Mark on the Wall [1917]) to evidence the redeeming character of the catastrophic for melodically constructing a humanism. Playing a blue note inspired by the tonal progressions of these prevenient writers’ works, West focuses on Plato’s Republic in connecting with the catastrophic to attain unto a humanism of community. Here, using what could be construed as a Ricœurian hermeneutical approach, issuing “[…] the self-contained existence of the literary work,”[4] “[…] which severs it from the present of the writer,”[5] which “[…] is still governed by the dialectic of event and meaning,”[6] West makes use of the semantic autonomy of the following passage from Plato’s masterwork:

“Homer is the most poetic of poets and the first of the tragedians, but we must know the truth that we can admit no poetry in our city save only hymns to the gods and praises of good men.”[7]

For West, it is not that Plato wished to rid his model city of poets altogether, it is that he desired that there be no “mimetic poetry” in the society. This mimetic poetry is one that is a music most deleterious because it does not allow for the individuated expression mindfully sunk into the greater whole of the community. West regards the Republic as a “treatise on education,” and, as such, is a heuristic on the development of the phronesis (φρόνησῐς) of dialogical and dialectical thinking, not the mindless recreation of forms and types of men thought to be exemplars of humanity, akin to what Immanuel Kant writes in “What Is Enlightenment?” (1784), that “[…] of the great masses a few will always think for themselves, a few who, after having themselves thrown off the yoke of immaturity, will spread the spirit of a rational appreciation for both their own worth and for each person’s calling to think for himself.”[8] When Lester Young, the greatest tenor saxophonist of Swing, says of the art of Jazz music “You’ve got to be original, man,” he is describing the insufficiency of following the order of Achilles, Odysseus, Hector, and Ajax, but, like West, inviting us, along with Socrates, to supplant Homer’s heroes for a raised consciousness of collective individuality. When Socrates leaves Athens (the place of wisdom) and goes down to Piraeus (the locus of the common man) to observe the feast rituals, he submerges his individuality in the topography of the landscape, both social and geographic, engaging the young men of Athens in maieutic interlocution, though never identifying fully with their sufferings. Perhaps, this is why, while Jesus weeps, Socrates does never. As Richard Rorty demythologizes, Karl Marx demystifies, and Jacques Derrida deconstructs, how approximate can they arrive at contingent truths if they but think about philosophy and not engage in philosophizing as a praxis itself? When Socrates does not weep but Jesus does, who most reasonably arrives closest to the sonorous effect/affect of the daimon, of music at work in the demos?

As Richard Rorty demythologizes, Karl Marx demystifies, and Jacques Derrida deconstructs, how approximate can they arrive at contingent truths if they but think about philosophy and not engage in philosophizing as a praxis itself? When Socrates does not weep but Jesus does, who most reasonably arrives closest to the sonorous effect/affect of the daimon, of music at work in the demos?

The Death of Socrates, Jacques Louis David (1787)

His insistence upon the ethos of a Palestinian Jew named Jesus, perhaps the mood of West’s Metaphilosophic Andante is one of life emergent from death. Perhaps the song at the heart of Goethe’s daimon that West intones in this lecture is toward a funereal ethics. In the Gospels, Jesus teaches that we are already dead. John 12:25, “He that loveth his life shall lose it; and he that hateth his life in this world shall keep it unto life eternal,” presents life as a death category, a negation. Jesus is making life death by suggesting that if one loves their life, they will lose it. Surely, Jesus is not suggesting that if one loves their life that they will die immediately, that their soul will be required of them. Rather, he is most reasonably saying that if one is loving one’s life, the pleasures of one’s life, as though one is never going to die, as though one is going to live forever, the fallacious nature of that mode of thought is tantamount to not living at all. In the verse, Jesus goes on to say that if you hate your life in this world, you will keep it as eternal life. This is another death category pronounced by Jesus, that is, hating life, a negation. Socrates makes a similar utterance in Plato’s The Phædo, his swansong, in a dialogue with Simmias as recounted by Phædo:

Socrates: Do you think that it is right for a philosopher to concern himself with the so-called pleasures connected with food and drink?

Simmias: Certainly not, Socrates.

Socrates: What about sexual pleasures?

Simmias: No, not at all.

Socrates: And what about the other attentions that we pay to our bodies? Do you think that a philosopher attaches any importance to them? I mean things like providing himself with smart clothes and shoes and other bodily ornaments; do you think that he values them or despises them—in so far as there is no real necessity for him to go in for that sort of thing?

Simmias: I think the true philosopher despises them.

Socrates: Then it is your opinion in general that a man of this kind is not concerned with the body, but keeps his attention directed as much as he can away from it and toward the soul?

Simmias: Yes, it is.

Socrates: So it is clear first of all in the case of physical pleasures that the philosopher frees his soul from association with the body, so far as is possible, to a greater extent than other men?

Simmias: It seems so.

Socrates: And most people think, do they not, Simmias, that a man who finds no pleasure and takes no part in these things does not deserve to live, and that anyone who thinks nothing of physical pleasures has one foot in the grave.[9]

This funereal ethics is an ought of how the human should live, realizing that there is nothing else but death for the self, thus predicating action away from self, and into community.

There is nothing morbid about this death talk. To be fully human is to already be dead. That is the lesson that we learn from both Jesus and Socrates. Hate your life because you are already dead. This funereal ethics is an ought of how the human should live, realizing that there is nothing else but death for the self, thus predicating action away from self, and into community. Socrates goes so far as to say that “[…] the right way to philosophy [is] of [one’s] own accord preparing [oneself] for dying and death […], looking forward to death”[10] all one’s life, making it “[…] absurd to be troubled when the thing comes for which [one] [has] so long been preparing and looking forward.”[11] Thus, with this pronouncement, both Socrates and Jesus, speaking in death categories, attempt to wrest the human subject from the confines of solipsism and sensitize them to the world of community. Funereal ethics is a call for the end of politics itself in that, as Hannah Arendt notes in On Violence (as inspired by Fanon) that “[d]eath, whether faced in actual dying or in the inner awareness of one’s own mortality, is perhaps the most antipolitical experience there is [,] [signifying] that we shall disappear from the world of appearances and shall leave the company of our fellow-men, which are the conditions of all politics.”[12] For, once theology has assuaged the anxiety of guilt and condemnation and philosophy the anxiety of fate and death,[13] all that remains is community, what exists outside our personal and insular sphere of self.

Through his Metaphilosophic Andante, this walking tune, progressive and processional, when West expresses solidarity with the thousands upon thousands of Palestinians deadened by the fascist occupying force of Israel, he expresses a funereal ethic, an ethological posture in which he sees himself as already inhumed, already in burial, thus empowered to reach outward from a cloistered approximation of self and into the deepest of humanisms, always connected, always in tune with the fellowship of the species.

[1] Huey P. Newton, “Black Capitalism Re-Analyzed I” in To Die for the People (New York: Vintage Books, 1972), 102.

[2] Ralph Waldo Emerson, The Early Lectures of Ralph Waldo Emerson: Volume II (1836-1838), ed. Stephen E. Whicher, Wallace E. Williams, and Robert E. Spiller (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University, 1964), 340.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Paul Ricœur, Interpretation Theory: Discourse and the Surplus of Meaning (Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1976), 91.

[5] Ibid, 35.

[6] Ibid, 25.

[7] Plato, The Republic, 607b5

[8] Immanuel Kant, What Is Enlightenment? (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 1992), 1.

[9] Plato, The Phædo (London: Oxford University Press, 2009), Lines 64d-65a

[10] Ibid, Line 64a

[11] Ibid.

[12] Hannah Arendt, On Violence (London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970), 67.

[13] Paul Tillich, The Courage to Be (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1952), 206-207.

Recent comments