John Dupré Lecture 4: Personal Identity.

Professor Dupré bravely faced his fourth lecture on a bank holiday Monday, to a well-attended audience. The Lecture was chaired by Professor Lesley McAra, which included interesting reflections on how the process framework might relate to the criminal justice system, and involved lively questions. A response by Msc English Literature Student Anand Narayanan Neelamana Sankarankuttan follows this summary.

Dupré set out his aim for this lecture—to apply a synthesis of “processual animalism” to understanding an organism, and apply this concretely to how we, as humans, operate in our world.

The first tricky question posed to the audience—what is it for a person to persist over time? Dupré introduced John Locke’s tale of the Prince and the Cobbler, where each wake up in the other’s body. (2003 perfected this 17th Century philosophical experiment with the film Freaky Friday).  Dupré points out how we can image waking up in another’s body, showing how we distinguish between our minds and our body. It is furthermore, only the co-occurrence of these two transformations that stop us being convinced that the Cobber and the Prince have simply gone mad. For Locke, the two important things in this story are the consciousness and memory of the two characters. Materialists would reject this separation and hold that mental properties reside in the body. Dupré takes a different approach again.

Dupré points out how we can image waking up in another’s body, showing how we distinguish between our minds and our body. It is furthermore, only the co-occurrence of these two transformations that stop us being convinced that the Cobber and the Prince have simply gone mad. For Locke, the two important things in this story are the consciousness and memory of the two characters. Materialists would reject this separation and hold that mental properties reside in the body. Dupré takes a different approach again.

More recently, rather than focusing on memory, we think of the body as determining identity. Dupré would want to stress that rather thinking about if there is one or two things that make up a human person, we start with the idea that there are no things that make up a human person. The human process is not a thing. It is a process with no limit about how many changes it can undertake. And following this, the human identity is overrated.

In examining animalism, Dupré outlined how he agreed with much of its position. A recent conference poster described animalism as believing that, ‘our fundamental nature is given not by our psychological capacities, but by our biological constitution: we are primates (Homo sapiens), and like all organisms, we persist just in case we continue living.’ Those who have attended Dupré’s previous lectures might guess that he has an issue with the idea of our ‘fundamental nature.’

All humans have hearts, brains, livers, etc. But so do all vertebrates, probably. Only humans have flown to the moon or written a novel; but most humans have done neither. A property of all and only humans is much harder to find.

If a human dies, or transmutes into a porcupine, they cease being human, but they still have been born to human parents. Extending the idea of a fundamental essence, think of a beetle, through egg, larva, pupa and adult. What property do these stages have in common that constitutes them as parts of the same life cycle, Dupré challenges. Considering that we can trace each species to LUCA, and how genes diversify and change, ‘feature unique to a species are unlikely to be universal within a species.’

Moving towards thinking about the persistence of processes throughout time, rather than identity as individual ‘things’, we need to embrace how processes depend upon other processes. Dupré uses the term ‘promiscuous freedom’ to describe how an ant may be considered an individual or a constituent of a larger hive process.  He also used Heraclitus’ famous example of the river, comparing the combination of the lower Mississippi and Missouri, which is longer than the Mississippi, but the latter carries more water. He pointed to historical events that characterized them so. Yet, ‘there is surely no difference of kind between the two candidates for being the river, and the two candidates for being tributaries.’ Following this, why do we characterize rivers from streams from lakes that serve as rivers etc, where they are all ways of distinguishing parts of a process of moving water from A to B.

He also used Heraclitus’ famous example of the river, comparing the combination of the lower Mississippi and Missouri, which is longer than the Mississippi, but the latter carries more water. He pointed to historical events that characterized them so. Yet, ‘there is surely no difference of kind between the two candidates for being the river, and the two candidates for being tributaries.’ Following this, why do we characterize rivers from streams from lakes that serve as rivers etc, where they are all ways of distinguishing parts of a process of moving water from A to B.

Where a new river comes out of another is also a tricky thing to pinpoint. Conception, where two processes intersect ‘is surely consequential’, whether the two rivers ends and one continues at some point can be applied to the messy relationship of pregnancy- ‘we should not look to biology for an answer’ to this question that is seeking a firm cut-off point. A life stage of a organism is one process, but we do not need to state that at each process it is of the same kind- think of a tadpole turning to a frog, or the changing from a prey animal to a predator throughout the cycle, or even of things—how currently Dupré is using Plato’s compete works as a doorstop, until he replaces it with Principia Mathematica—are they doorstops or books?

Human processes however, are uncontentious. ‘People are born, named, given various identifying numbers, and tracked throughout their lives by various bureaucracies until their deaths are certified.’ There is a process that leads from fertilized egg to baby, teenager to eventually death. There is an issue with calling this whole process a human- is the zygote a person? Dupré holds that this is too early—relating back to Thursday’s discussion. He used a quote from Ronald Reagan, ‘Unless and until it can be proven that the unborn child is not a living entity, then its right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness must be protected’, to point out how we should not accept that every living thing has a right to live, liberty and happiness—extending this to cholera bacteria for instance would deny our right to live.

Why then, Dupré asks, do we individualize the human process? His first answer is organizational purposes for us to run our society and manage the distribution of responsibilities. Here, we can relate how selfishness is considered a moral flaw (or not so much under neo-capitalism), but in former historical societies selfishness was unusual. Though we do seem to have stronger bonds with certain people—we would be uncomfortable in strangers came to family lunch—but perhaps we should not be Dupré challenges.

We all, or almost all, have names and social security numbers; most of us have telephone numbers, email addresses, and a totally unmanageable number of passwords for accessing our internet spaces. We issue birth certificates, death certificates, identity cards and passports; many of us now carry quite sophisticated face-recognition and finger-print identification technologies in our pockets.

If we do away with the idea of an essential essence or soul, we can see these tracking devices as contributing to the construction of identity rather than mirroring or recognising something that already exists.

David Lancy distinguishes ‘pick when ripe’ and ‘pick where green’ cultures, where some contexts give babies and infants a village curriculum where they are part of a younger, helping whole, only later being fully recognized as individuals, contrasting with our own culture, stemming from Protestantism in the Netherlands, in which babies are never too young to be individualised. The former idea better reflects historical and cross-cultural norms, and Dupré stresses, ‘personhood is a concept imposed on the animal life cycle for variable parts of the life cycle and reflecting wider social interests.’

Derek Parfit reaches similar conclusions that what matters is the connection between one’s present experience and one’s memories—but that this is not enough to constitute an induvial identity. When he released himself of personal identity the inevitability of his death seemed less tragic. Dupré extends this and considers how we do not remember so many parts of our lives, and also wonders how our present justice system that punishes people over long-lengths of time relates to this deconstructing of identity.

One of the most serious problems of our time is the obscene and rapidly increasing inequality between people in most countries of the world.

People believe themselves entitled to the fruits of their labour (or as alluded in previous lectures, the results from the exploitation of the labour they manage), but the chains of identity problematize this. Heritocrcay is another example of dysfunctional wealth hoarding through ideas of closed identity formed in families.

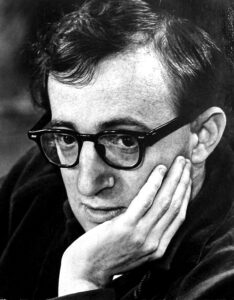

Dupré ended his lecture by considering the work ongoing to extend human life into immorality—either by trying to stabilize one life change, or by forms of transhumanism. He uses Dawkins’ chapter in The Selfish Gene (1976) which talks about the immortality of genes, where gene lineages are processes which are constantly replaced, and have impressive longevity. Immortality is considered to be possible in some sense through offspring or through a life’s work (academic, charity, tomb stone etc). For Woody Allen, this wouldn’t be enough, “I don’t want to achieve immortality through my work; I want to achieve immortality through not dying. I don’t want to live on in the hearts of my countrymen; I want to live on in my apartment.”

Do those with surplus wealth feel it unjust that they cannot buy their immortality? Processes persist by the continuity and interconnectedness of the activities that maintain them, not by an ‘unchanging and immortal essence.’ So, how does a person in 1000 years relate to the one now, apart from historically?

a ball cannot roll downhill for ever; and likewise it is not obvious that the developmental trajectory of a human can be extended forever […] the misguided analogy with maintenance of a machine makes the plausibility of indefinite life extension much less problematic than would a more accurate picture of a process with a characteristic trajectory and a typical temporal duration.

Thinking in processes questions how we perceive separation, beginnings and ends. The way humans exist through changes internally and stabilization processes externally brings to light questions of what might be left when divorced of these connected processes.

Response: Anand Narayanan Neelamana Sankarankuttan

In Under the Udala Trees (2015), Chinelo Okparanta introduces Ijeoma, a lesbian character who struggles to fit into the homophobic society. The novel was written in the aftermath of Nigeria criminalising gay relationships. Okaparanta structures Ijeoma with the memories and consciousness of her ancestors in pre-colonized Africa where lesbian relationships and marriages were prevalent. So, the ‘identity’ of Ijoema is much more connected to her ancestors than the people around her. This can be related to Professor Dupré’s thoughts and arguments about one being connected to their ancestors like how Homo Sapiens are in relation with LUCA, our ancestor. He further brings attention to something he refers to as “promiscuous individualism” where an organism can be considered as an independent individual or a constituent of the larger hive process, such as in the case of an ant. This hive mentality or hive individualism, in my opinion, is very common among marginalized communities or suppressed communities or the category of the subaltern. Since the people belonging to the subaltern rarely get any space or opportunity to talk and express their own opinions, the opinion of one of them becomes the opinion of the community. One individual represents the memories and past experiences of the community they belong to. This was discussed during the question-and-answer session where the ‘shared trauma’ of the African American community was brought to attention. The shared trauma mentality goes to the LGBTQ+ community as well.

Professor Dupré’s arguments about the human being as a ‘process’ was well received by the audiences including myself. We never stop growing both physically, mentally, and psychologically. Even after hitting a stage where we are said to ‘stop growing’ as in literal terms, we still grow new cells and shed the old ones. With respect to our mental growth, it is an ever-evolving process. I believe that our identity as well is a continuous and growing process. One’s eight-year-old self is completely different from their twenty-year-old self. The hive consciousness, as I have observed, comes towards the end of puberty where one becomes more and more confident in their own identity and finds comfort in a community that shares similar beliefs.

In Animal Farm (1945), George Orwell writes about the events leading up to the Russian Revolution and then onto the Era of Stalin by making all the major characters into animals at a farm. He easily transfers the consciousness of the human characters into the animals. The animals behave like humans. Professor Dupré talked about how if a human dies, or transmutes into a porcupine, they cease being human, but they still have been born to human parents. Orwell’s animal characters are examples of that. Even though they’ve been transformed into animals, they still pertain human characteristics and at times express those characteristics. It is as if those attributes are stored inside their mind and they come to the surface at important times. This exemplifies how creativity and fluidity are intertwined through our physicality and our minds. Dupré’s process perspective could be a lens with which we analyze literature, or perhaps a lens that might spark new ideas and writings as we continue to grapple with questions of identity, community and connectivity.

Recent comments