Lecture 6- Paul Robeson: Art in the Service of Heroism

‘The very highest of which humankind is capable.’ Neiman believes this phrase is entirely applicable to Robeson. She points out that she had nevertheless not known of Robeson until her Chilean friend gifted her some albums in 1988, since his memory has been virtually erased in America. His voice was known to her but not his story due to him being blacklisted during the Cold War.

‘The very highest of which humankind is capable.’ Neiman believes this phrase is entirely applicable to Robeson. She points out that she had nevertheless not known of Robeson until her Chilean friend gifted her some albums in 1988, since his memory has been virtually erased in America. His voice was known to her but not his story due to him being blacklisted during the Cold War.

Before his fame came from acting and singing, Robeson made newspaper headlines from his achievements in American Football. This, alongside his other sporting talents, being a champion debater, keen linguist and well-rounded scholar earned him a full scholarship to Columbia Law School. He wanted to work in what we now know as civil rights law but a secretary at the form would not type from the words of a black man, so he quit. He went onto try amateur theatre and was soon signed to star in two plays and toured London and New York. He was a determined actor, even attending medical classes to portray Othello’s epileptic fit realistically. He also brought his own interpretations and emotion to his roles. He changed the lyrics to Showboat after the Spanish Civil War, overcoming the racist assumptions in “You get a little drunk and you land in jail” to “You show a little spunk and you land in jail” and he altered “I’m tired of living and scared of dying” to “I must keep fighting until I’m dying.” Despite allowing his creativity to come through some films, generally, they were poor and riddled with racist overtones. He thought he could change the trade from the inside but eventually turned to music instead.

His father was of Igbo origin but was born into slavery. He escaped as a teenager, learned several languages himself, and became a minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Princeton (until he challenged the white power structures and was removed). Sadly, his mother died in a fire when he was six.

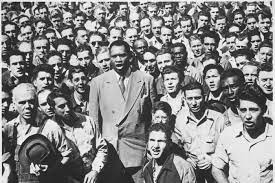

Paul Robeson received a scholarship from Rutgers, only one of two black students to study there during his time. He was the star of the choir and sports team but still was the subject of racist violence. In his first team the football team beat him up severely. He was still subject to discrimination when he became according to Du Bois ‘the most famous American in the world.’ He was told by a steward on an ocean liner in 1939 he and his family would have to eat in their room. They all ate in the middle of the dinning room. ‘The fact that he was able to channel the rage he surely felt into disciplined determination to more achievement is itself a testimony of nearly superhuman strength.’

“Robeson set the bar not only for Black but for human accomplishment in a world that saw Black people as inferior – a perfect excuse for excluding them from power.”

He once said that he believed he was the only black man alive who ‘didn’t want to be white.’ He wanted his achievements to help lift up other African Americans. In London, Robeson met young anti-colonialists like Jomo Kenyatta and Kwame Nkrumah and began to study African languages at SOAS. He became committed to Pan-Africanism and the idea of independence for African countries. His eye was never blind to other kinds of suffering or beautiful however. He loved performing Shakespeare and always wanted to learn more about other cultures. He studied music theory to try and prove that folk music derived from the same platonic patterns. “If you’re feeling provocative, you might call him a hero of cultural appropriation, a concept he would have rejected entirely. On the contrary, he believed that working to enter into another culture is the only way to understand its people’s humanity.” Neiman points to how this dual loyalty to your nation and loyalty to universalism is hard to understand. That the Bund did not make it through the Holocaust but other Jewish movements did is a good example of how holding both is difficult for many. Also threating to universalism today is its confusion with globalism- one is socialist, the other neo-capitalist.

“His political education took place during his years in London, where he consorted with aristocrats, but also with labour theorists and activists like George Bernard Shaw, Emma Goldmann, C.L.R. James, H. G. Wells, Jawarharlal Nehru, and many others.” He was also influenced by less influential people in Britain, especially Welsh miners. In 1929 he met a Welsh Male Choir who walked all the way to London to demonstrate against their awful mining conditions. He paid for their return trip and provisions for their families. He was invited to perform in the national Eisteddfod (the cultural festival of Wales that is traced to 1176) through telephone (at this time Robeson was denied a passport) and the National Museum of Wales often has exhibitions about him even today. Robeson saw music’s power to move people and brought resistance traditions together through songs- songs of the Spanish Civil War like “Los Cuatros Generales” with the American “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” the Yiddish “Partizanenlied” with the Black spiritual “Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel?” for example.

He pushed the US and Britain to support the Spanish Republic against Franco and even founded the “Negro People’s Ambulance for Loyalist Spain.” For Robeson as for millions of others, fascism stood for racism, violent oppression and war; communism for universal human rights.

Robeson took his family from London back to America just after the Wehrmacht invaded Poland. When the States joined the war he patriotically joined the war effort. Interestingly he refused to sing at the White House because of Roosevelt’s inaction about racism but campaigned for his re-election in 1944. “In his speeches during the war, Robeson drew connections between European fascism and American racism, insisting that one could not fight for freedom abroad while countenancing the Ku Klux Klan at home.” This was monumental for recruiting African Americans in supporting the war effort.

During the Cold War Robeson’s politics became even more outspoken, especially concerning his support for the Soviet Union. “His downfall came with the Paris Peace Conference of 1949, where he was quoted as saying that people of color would not fight against the Soviet Union. While his speech was misquoted, he’d committed two unforgiveable sins: criticizing U.S. policies – in this case segregation – while speaking abroad, and praising the Soviet Union – in this case for its antiracist policies. Together, both sins provoked cries of treason.” The black community worried this would threaten their belonging to the States. He was nearly lynched in Peekskill, a small town in upstate New York where he gave a benefit concert for a civil rights organisation in Harlem. After the rightwing violence his bookings were cancelled and reduced. His annual income dropped from $150,000 to $3,000. In 1950 the US State Department cancelled his passport and the press accused him of being a Soviet agent. It took eight year before he could travel again but he was still celebrated around the world and many eagerly awaited his resurgence. He worked too hard after his release and his physical and mental health deaerated. He slashed his wrists in 1961 and spent some time in the Barveekha sanitorium and later a London clinic that were fond of electroshock therapy that moved him to a near-cationic state. His condition involved after spending time in a clinic in Berlin but after his wife died in 1965 he was never seen publicly again.

His family life complicates the story, but Neiman believes other parts of his life are more worthy of attention. His support of the Soviet Union is a dynamic section of his life. He even sent his son to school in Moscow to avoid the racism of the States. “Robeson never spoke out publicly against the Soviet Union. When asked why he didn’t, he said it was the business of the Soviet people, not that of an outsider.” It was never entirely clear how much Robeson knew of the less-than-ideal parts of the Soviet rule, but some have interpreted him as naïve. Neiman believes however Robeson simply had to pick the lesser of two evils.

“For Lenin, racism, imperialism and capitalism were inextricably mixed. Stalin’s constitutional amendment forbade discrimination on the basis of skin color or language – thirty years before such a law could be passed in the United States. Moreover, the Soviet Union proclaimed a deep appreciation of the power of culture, a view that must appeal to every artist and intellectual, particularly one who, like Robeson, already believed that music is the quickest way to foster understanding between peoples.”

Rather than being ignorant, Nieman presents Robeson as brilliant and learned, benefiting from his cultural experiences and language learning. Like much of the world, Robeson suspected that the militarily unnecessary strike of Hiroshima which killed 150,000 in an instant, was in fact a signal to Stalin. She urges us to see beyond the alleged similarities between Fascism and Communism and honour the will to truly create an egalitarian society that values humans as humans.

“At the beginning of the campaign against him, Robeson received a personal message from Secretary of State Dean Acheson, offering to end government harassment if he promised to refrain from making political speeches or singing at political meetings. Interestingly enough, the American Communist Party later made a similar suggestion: Robeson should stop his political activity and stick to singing. Robeson rejected both.”

His dedication to socialism was a threat. The States had stamps of Minnie and Mickey mouse before Robeson. “Understanding those choices is crucial to understanding the history of the 20th century so sorely in need of discussion today. For the post-Cold War order’s consensus – that any form of socialism leads to terror – has prevented us from asking if another form is possible.”

Blog Response Michael Harris

The theme of this lecture was heroes and those who are regarded as one of history’s heroes. The lecturer, Dr. Susan Neiman, regards Paul Robeson as one of those heroic persons. Heroes are similar to those who are regarded as one of the Great Men and Women of history. Based upon the great man theory of history developed by 19th century Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle, this theory promotes the idea that history can be better understood by studying how great men and women or heroes have influenced history.

Robeson accomplishments went far beyond those of the ubiquitous Black American athlete and entertainer. Although he was a renowned athlete as a member of the Rutgers University football team, Robeson also graduated at the top of his class and went on to earn an ivy league law degree from Columbia University. Unable to acquire a fulfilling career as an attorney in 1920s America, he subsequently began a career as a theatrical performer who was highly regarded for both his acting and vocal talent. Furthermore, Robeson also achieved success as an actor in film. He left the film industry due to his frustration over the degrading roles assigned to him, however this led to a political Robeson.

Professor Neiman emphasizes that Paul Robeson possessed universal values. One aspect of this was around forging class solidarity with the working class in both United States and internationally. (He was more successful in the later as class solidarity was and remains a difficult goal in the United States due to success of race baiting politics). He sought to understand the culture and reality of other ethnic groups as well as he understood Black American culture and the Black American experience. Moreover, Robeson believed in the oneness of humankind despite him being a person who was fervently committed to communicating the hopes and improving the image of the Black American community.

When it comes to remembering Paul Robeson’s life, I was intrigued by the information concerning anti-communist politics in the West. The sad reality is that Western leaders, including Adolf Hitler, perceived the opposing ideology of communism to be more of a threat to the West than German Nazism or European and northeast Asian fascism. Such a political scene made Paul Robeson an opposing figure in American society. For him, communism stood for universal solidarity and fascism stood for racism and imperialism. Robeson stood for liberation of those of African descent in the United States and decolonization of the African continent. The Communist Party supported for the former and the Soviet Union supported the latter. But such passions led to his persecution in post-World War II American despite him being a highly regarded during the war for singing patriotic songs. The political Robeson of this era began to demonstrate heroic courage by publicly speaking against racist practices in the United States. He was favorable to the Soviet Union for its government’s progressive racial policy. He was favorable toward the Communist Party because of the public policies it promoted, even though he was never a registered member or activist for the party in the United States.

The unfortunate reality is that Paul Robeson, like many Black American activists, found a more loving and supporting community outside the United States than he did from mainstream White America. However, was Paul Robeson specifically responsible for his own downfall due to his unwavering support for the Soviet Union? Robeson support for that nation state and the communism was a support for the lesser of two evils, similar to many contemporary Americans and their support for Donald Trump and populism due to a belief that a figure like Hilary Clinton or the progressive left are more evil. Robeson also advocated petitioning the United Nations regarding the racism and oppression experienced by Black Americans in the United States (a position also advocated by Malik el-Shabazz/Malcom X). We must also remember that Paul Robeson was in his mid 60s when legal and de jure segregation officially ended in the United States, an age by which he had firmly made up his mind regarding the reality of life in that nation. Professor Neiman emphasizes that Robeson was indeed a broken man by the time of his death in 1976. This indicates that the persecution he endured from American officials had defeated him. Robeson is indeed a hero of history due to his professional accomplishments and the bold public stances he prevailed in defending until the very end. Detractors may conclude, however, that his brokenness harmed his legacy and the decisive influence he could have had upon history. One’s position or conclusions on that would determine if he or she also regards Paul Robeson as a heroic historic figure. I conclude that Robeson’s defiance for core beliefs as well as the class he exhibited as a performer outweigh any broken image of an elderly man and hence, his image as a historic hero will prevail.

Lecture Video

Recent comments