Lecture 5- Einstein: How to Turn a Hero into a Celebrity

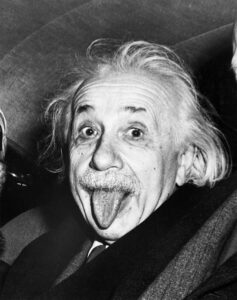

Albert Einstein sticks out his tongue when asked by photographers to smile on the occasion of his 72nd birthday on March 14, 1951.

The photo of Einstein sticking out his tongue captured public attention in his day and continues to represent popular opinion of him today. Neiman admitted that she had this image of him in her head when she took up the position of Director at the Einstein Forum, in fact, in 2000 she admits that she ‘didn’t even like him.’ He was ‘a vaguely comic genius with his head in the clouds, a sweet guy, to be sure, but one who was utterly out of touch with the world in which most of us live.’ In Yiddish this would be described as a Luftmensch- a person with their head in the clouds. J. Robert Oppenheimer called him childlike and Isaiah Berlin called him innocent. The opposite of this clown-like description is to be seen as Saintly. His unofficial canonization did not help him escape the mythical that comes with this label. The urge to destroy the elevation of the Saintly has led people to claim that he invented the atomic bomb, he neglected his children, and to concentrate on a hostile letter he sent his first wife. Einstein tried to make this Sainthood status an irony.

Avoiding Einstein became impossible once Neiman took up her current job. His photos caught her attention firstly through the power that emanated from his person even though he often looked unkempt “if they want to see me, I’m here. If they want to see my clothes, you can open the closest” he said to his second wife Elsa. He is also remembered for being forgetful.

“Did Einstein pretend to be a Luftmensch?” Neiman asks. He had a lot of the world to avoid considering his vast popularity. On further thought she came to the conclusion that he neither was or presented to be a Luftmensch at all, but has been presented this way so people could cope with him. “Einstein is such a hero for our time that he threatens people today, which is why, despite hundreds of biographies, so many of the reasons why he was heroic are unknown to the public at large.”

A curiosity and interest in everyone (that reminds us of George Eliot from yesterday) led Einstein to invite his binman to tea more often than he did the President of Princeton. His fame was not because of his physics (that went over the heads of most of his followers) but because of his goals in the spiritual and moral domain.

A Luftmensch is a sweet fool, but Neiman contests this label for Einstein by demonstrating his hard-working nature, his attention to detail, and his media savvy. He worked as a patent officer after not landing a job after his doctorate (this blogger is wondering if that should give aspiring scholars hope for securing an academic position one day or instead should we lament that even Einstein wasn’t hired?!) Einstein declared that half of his life was devoted to equations and the other half politics. In 1934 he shared that “Striving for social justice is the most valuable thing to do in life,” and the latter half of his life was committed more to this aim than to his science- he wrote more than 200 political essays! He understood the value of his endorsements and supported loyally causes he believed in- even when they were unpopular.

He had a disregard for convention that traces back to his school days where it was not the case that he was not good at school but more that he just disliked it. His insolence also made his teacher nervous. Many belief that this suspicion towards convention was crucial for his scientific discoveries. He also had an interesting relationship with religion. He did not subscribe to a strictly institutional type but had a sense of awe and wonder: “Veneration for this force beyond anything that we can comprehend is my religion. To that extent I am, in fact, religious.”

“The value of a man should be seen in what he gives and not what he is able to receive.” Neiman categorizes his work into four causes- his work against war, against political repression, against racism, and in favour of socialism. He put his reputation in danger during WW1 when Einstein was one in four of the 100 German intellectuals approached to sign a letter calling for the end of war and the creation of a united Europe. This was a serious risk. In England, Bertrand Russell’s pacifist stance put him in prison and Russell was not a Jewish Professor. To achieve his first professorship in Zurich a letter had to be sent from a supportive colleague that declared Einstein was free from disagreeable Jewish qualities. Neiman outlined that during this time many Jews converted to fit into the culture and praised Einstein’s courage. Einstein had a wager on his head in Berlin and the orchestrator was only fined. Nevertheless, his refusal to ‘blend into the background’ continued with his role in Princeton that acted as a refuge. He continued to be a public intellectual and organised a concert to benefit Jewish refugees in 1933 to the despair of the quiet Abraham Flexner, director of the IAS. His conviction continued throughout the cold war and he wrote the foreword to Gene Sharp’s book on Gandhi.

He was worried about the rising antisemitism in Europe and supported the drive for a Jewish homeland. This aim was accompanied by universalist concerns. In a 1929 letter to the President of the World Jewish Congress he urged for cooperation and an honest pact with the Arabs. He hoped there would be a binational state in Palestine. (There was no Jewish state until 1948 so it makes little sense to say he couldn’t see it.). Einstein had a good relationship with Ben-Gurion and was asked to be president of the State of Israel, though Ben-Gurion admitted after sending the invitation that they would have been in trouble if Einstein had accepted. Neiman posed that Einstein spoke to truth to power, which would have made Ben-Gurion’s role tricky.

Einstein also had an anti-racist passion, testifying for W. E. B. Du Bois, inviting singer Marian Anderson who was denied a room at the Nassau Inn to his house, and having a strong friendship with Robeson whom he met after a benefit concert Robeson performed for the Black YMCA in Princeton. In 1946 he wrote, “equality and human dignity is mainly limited to men of white skins. Even among these there are prejudices of which I as a Jew am clearly conscious, but they are not important in comparison with the attitude of the ‘Whites’ toward their fellow-citizens of darker complexion, particularly toward Negros.” His usual practice was to turn down University invitations but he accepted a degree from Lincoln University- the first University in the States to offer degrees for African Americans.

Neiman demonstrated that his strong socialist commitment is still a taboo today. During his time in the States the FBI was looking for an excuse to deport Einstein- also meaning he could never have got security clearance to work on the Manhattan project. He distrusted the Soviet Union and Capitalism and was rooted in Socialism with a keen awareness of the evils of economic injustice. His 1949 essay ‘Why Socialism’ highlights the hidden labour of millions that allow for the thriving of the individual and the issues that arise from their discontent. As early as 1932 the Women Patriots claimed he was worse than Stalin who tried (unsuccessfully) to prevent him from getting a visa. He was offered unconditional citizenship the year after but accepted no special treatment to speed up the process. He openly criticised the anti-Communist rhetoric in the States despite never being tempted himself. He used his influence to help young people who were threatened for refusing to serve in the army or to go along with the HUAC and promoted civil disobedience, telling friends to prepare for jail or economic ruin to stand for what they believed to be true. At the same time, he did whatever he could to prevent their economic ruin by helping persecuted people find jobs. ’As long as Einstein’s socialism is written out of his life story, the McCarthyites have succeeded in intimidating us from beyond the grave.’

Heroes make us uneasy because they represent ideals we could follow, demands we could make: to increase our expectations of our own lives, to become a little less certain about what‘s realistic, and which pieces of the world might be changed.

The easy and concerning reaction to Einstein’s life is the commodification and undermining of his heroic stature that makes emulating them less appealing.

Lecture Response Allan Furic

Albert Einstein was one of the most prominent scientists of the last century, renowned around the world for his theory of relativity as well as his contributions to the newly emerging field of quantum mechanics in the 1920’s. His personality and genius were often received in a dual-polar love/indifference relationship, which is revelatory of the admiration people have cultivated for him, a trait central to the concept of hero. As such, he was the subject of the 5th lecture in the 2021/2022 Gifford lecture series presented by Professor Susan Neiman.

As director of the Einstein Forum in Berlin, she has been especially close to Einstein’s life and ideas, having oscillated herself from nearly complete disinterest of the man whom she perceived as “a vaguely comic genius with his head in the clouds, a sweet guy, to be sure, but one who was utterly out of touch with the world in which most of us live”, to a recognition of his heroic character. She advocates that the picture classically rendered of Einstein — evolving between the two extremes of “sad-fool” and “saint” — was in fact the consequence of a mysterious, if not mystical, aura that surrounded the man for most of his life, and that still has lasting results in today’s society. According to Professor Neiman, Einstein has been depicted through a set of what could be qualified as morally opposite behaviours: father of the nuclear bomb in the Manhattan Project while being an advocate of peace; bumbling professor in an article of the Time magazine versus an eternal child as presented in the German newspaper Die Zeist; altruism especially in the case of other people’s children, despite him having neglected his own; and so on. The latter case is in fact quite analogous to a certain Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who wrote a treaty on education and abandoned his three children to the welfare state. The moral compass is definitely not dependent upon one’s intellect. Everything is basically making Einstein look like an individual in a state of superposition, to employ the metaphor of wave/particle dualism in quantum physics, who was hence put at a sufficient distance from the lay men so as not to trigger an unpleasant questioning of one’s life purposes and motivations.

But Einstein was more than that. As Professor Neiman recalls, he was marked by an “anti” attitude towards racism, political repression, and war, with the exception of the second world war, in which in took a stance by strongly disavowing Nazism and called for action as a result. He was at the same time engaged in political questions, especially in his later life, and pro-socialism, which caused him to be under the scrutiny of the then director of the FBI for suspicion of relation to communism. While he managed to escape the threat of deportation until his death, few others were not so lucky, notably the famous physicist David Bohm who was forced to flee respectively to Brazil, Israel, and the United-Kingdom, and lost his American citizenship in the process. Here, Einstein appears certainly less heroic than Bohm, whose misfortune attracts sympathy and a sense of awe facing the self-sacrifice that Bohm went through to stick with his ideals.

While I agree with Professor Neiman that the Manichaeisation of Einstein as a Luftmensch does not do justice to the man he was and his engagement for matters of the world throughout is life, I cannot for all that neither understand nor acknowledge that his heroism is based on a picture that neglects the utmost importance of his physics. Although it is understood in the context of professor Neiman’s lectures that the focus is on moral heroes, one willing to emphasise Einstein’s heroic life cannot underestimate what is likely to be the cause of his fame and admiration, namely his achievements in physics. For instance, when mentioning at the beginning of the lecture that the picture of Einstein sticking his tongue out is the most well-known depiction of him, which automatically comes to anyone’s mind when the name Einstein is spoken, professor Neiman fails to add that the equally-famous equation E=mc2 is always attached to his picture, for it is recognised as one of the most profound and paradigmatic discoveries of modern physics. Einstein’s fame in physics is not limited to the equation he published in the paper of 1905, but extends to several other discoveries, including notably the photoelectric effect which earned him the Nobel Prize in 1921, a new theory of gravitation in general relativity, and a substantial contribution to the earlier debates on the interpretation of quantum mechanics, as is exemplified in the lengthy discussions he had with quantum theory’s father Niels Bohr. Einstein’s imaginative and predictive power in his mathematical equations is in fact what elevates him to a heroic position, precisely because it constitutes an extraordinary achievement conducted by the mind of a single man, and which have since been experimentally demonstrated countless times. That does not mean that his societal implication does not play a part in the way he should be regarded as a hero likely to inspire lots of generations to come, but it shows that his success in physics places him on the level of the extraordinary. Considering that a hero is supposed to inspire people in transcending their limitations, in taking action and moving forward in times of despair, as timeless figures of humanity, one should be looking for the extraordinary in a person to qualify him/her as a hero in the first place, which Einstein had through his physics. Though he has always been a strong individual who conveyed a sense of “extraordinary power” by his simple presence, Einstein’s heroism would have definitely been limited in its scope had he not developed the ideas behind the equations that made him famous, ideas in fact so simple in their essence that they could be understood by anyone. Now, only a true heroic mind could have come up with such a fundamental, beautiful, and far-reaching simplicity.

Lecture Video

Two quick corrections: Rousseau abandoned not three but five children; Einstein did not abandon his own. He divorced their mother, Mileva, who received custody of the children and returned to Zurich, but there are many letters which show how concerned Einstein was over his two sons, even considering applying for custody, and visited them frequently. I showed a photo of him with his son, Hans Albert and his grandson, who visited him in Caputh. The rumor that Einstein neglected his children is just a rumor. Second, you claim that the famous photo with his tongue stuck out is always accompanied by E=mc2. A simple google search suggests the opposite. I am glad you feel that his revolutionary achievements in physics are so simple as to be understandable by everyone. Most people who are not physicists would strongly disagree – and those people are by far the highest proportion of his admirers.

In my opinion, Einstein is someone who changed the world