Text Analysis: Summary

The aim of this project is to use methods of computational analysis to draw out patterns of language and points of interest in a unique corpus of texts: the files of the Medical History of British India, held by the National Library of Scotland (NLS). A core tool in our analysis was a program called AntConc which allows a large corpus such as this to be analysed and searched in a variety of ways. This introduction will serve to frame the individual analyses of our ten contributors by outlining the methods we used to analyse this corpus and how this analysis fits into the wider discourse of digital humanities.

The Medical History of British India corpus (MHBI) is free to view and download via the NLS data foundry which provides open access to a number of their digitised collections. Firstly, the files were put through a process of optical character recognition (OCR) by NLS which converts scanned images of each written document into a machine-encoded text. These OCR’d text files are what we downloaded from the NLS site.

Our next goal was to Part-of-Speech (POS) tag the corpus, meaning each individual word or number was given an accompanying tag which identified its word type e.g. noun, proper noun, adjective etc. To achieve this, we used a Jupyter Notebook via GitHub which allows Python code to be integrated into an interactive document. First, we tokenized our corpus, which simply put, means we broke the text into its individual linguistic elements. Next we downloaded a POS-tagger which computationally tagged the entire corpus.

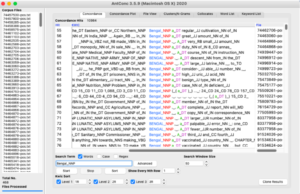

Once we had the POS-tagged files on our computers, we opened them in the AntConc program, which is also free to download. In the search field, we can search any word and its accompanying POS-tag in all 469 files. For example, to search for Bengal as a place name, we would search ‘Bangal_NNP’. Here, the NNP refers to the word type, which in this case is a proper noun. We will then be able to see all instances of this word as a proper noun and the surrounding sentence it appears in:

The use of ‘*’ or ‘+’ allows for a wildcard search; the ‘*’ equals 1 or more characters, while the ‘+’ equals zero or one characters. This allows for a more open and flexible search to be conducted. If we search for ‘quarantin*’ we open up our search to all forms of the word e.g. quarantine, quarantined, quarantines. The different combinations of search terms, wildcards, and POS-tags allow for highly flexible or tightly specific searching within the corpus. You will see numerous examples of such searches in our individual analyses and the benefits of AntConc for analysing a corpus of this size.

Analysing a corpus at grand scale would be long and tiresome work without the help of a computational analysis tool, AntConc. Overall, AntConc has allowed us to access and research the NLS Medical History collections with ease and efficiency. AntConc has made data available in machine-readable format therefore encouraging readers to interact and collaborate with computational intelligence in the hope of grasping a new understanding of the colonial rule in nineteenth-century India and its impact on the medical treatment of both Native and non-Native individuals. When handling a large body of historical literature and translating it into an organised data set, complete with POS tags and a quantified understanding of a qualitative object, digital humanists have addressed the benefits and drawbacks of these new methods.

In his essay, Distant Reading and Recent Intellectual History, Ted Underwood outlines the function of “distant reading”, which he defines as a useful method that is used for ‘larger scales of analysis’ (530). He argues that one disadvantage of the phrase distant reading is that by the use of the word “reading”, it implies a continuation of literary methods of reading, one that is contained within the literary realm and fails to acknowledge the multi-disciplinary nature of distant reading. A shift has occurred within the field of social sciences, that Underwood describes to be largely credited to the employment of distant reading techniques. As data sets have exponentially increased in size, due to digital libraries and the internet, new methods of “reading” data are critical in efficiently and innovatively analysing its corpora. AntConc is one particular platform that has, and continues to, assist in this intellectual shift from close to distant reading techniques.

Underwood also highlights how ‘sociologists could use numbers to understand social mobility or inequality, but they had a hard time connecting those equations to a larger and richer domain of human discourse’ (530/531). However, as we have found throughout our use of AntConc in our analysis of the MHBI data set, that barrier has been resolved. We have found that using a computational analysis program, connections between linguistic and social equations are readily available to understand and formulate. In our individual analyses of the qualitative data, we have extracted quantified evidence that serves as our claim to the social injustices and inequalities that are evident in the data’s reflection of nineteenth-century colonial India. By blurring the lines between qualitative and quantitative data sets, digital humanists and students can grasp a richer and more diverse understanding of the sociological and literary moments in history that in turn provide more awareness and visibility to subjects such as the medical history of colonial India.

Below you can find the detailed subjects of the analyses by our authors:

Iosif Pryor: “The Man Became Useless”: Idiocy, Psychiatry, and Empire-Building

Jaclyn Kerr: A Look at Eating Disorders in the British Medical History of India

Justyna Mignotte: Matter of Life and Birth

Lydia Housley: “Insanity caused by…”: Cannabis Consumption and Colonisation

Megan Clarke: Agency within the Archive; how the representation of Indian women worked to rationalise colonial strategies of surveillance.

Rachel Spero: Lunatic Labour: An Industry for Profit

Rioney Perera: Mistreatment or Treatment? Patients in 19th Century British Indian Asylums

Shuqing Liu: The Dufferin Fund and Female Medical Care

Victoria Ma: Venereal Disease: A Colonial Oppression on Indigenous Women

Photo by Nina Luong on Unsplash