Growing up as a creative teenager in Dundee in the early 1970s wasn’t exactly a walk in the park, and I’m fond of saying that my life didn’t begin until I went to university in Glasgow in 1975 and landed feet-first in the explosion of culture that was the city in that era. The Citizens’ Theatre was in it’s golden age, with lavish productions (the like of which had never previously been seen outside of London) featuring gender-bending direction by Giles Havergal and Robert David MacDonald and Met-Opera-quality design by the inimitable Philip Prowse. Scottish Opera had just refurbished the previously derelict Theatre Royal and were presenting everything from Verdi to Britten. Glasgow Film Theatre (GFT) had whole programmes of films that I had only ever read about in books, if I had even heard of them at all. And it was all so cheap! Students could go to the Citizens’ for twenty-five pence; standby tickets for the opera could be as low as a pound or fifty pence.

But most of all, there was an alternative zeitgeist that was being cautiously whispered in the back streets, that – if you were careful and avoided Ibrox and the other strongholds of toxic masculinity – it was okay to be queer in Glasgow. Male actors played women’s parts at the Citizens’ – and not just the pantomime dame – and a posse of Liza-Minnelli-clone drag queens regularly flocked to the Renfield Street Odeon when Cabaret (1972) was rerun on late night showings.

Queer Cinema, then, was a thing that existed in those days, even if it was just a little coy, just a tiny bit nervous about coming right out of the closet. True, Tim Curry was strutting his stuff as a sweet transvestite in the corset that Sue Blane designed for him for The Maids at the Citizens, but, in a little face-saving twist, the outrageously camp Frankenfurter is equally keen to bed Susan Sarandon and prove that all is still right with the world; and even in GFT’s groundbreaking queer cinema season – a programme peppered with such delights as Ludwig – Requiem for a Virgin King (Ludwig – Requiem für einen jungfräulichen König, Hans-Jürgen Syberberg, 1972), you could sense a certain reticence to go “too far”.

The awakening comes, of all places, at The Classic, an emporium better known for such porno epics as Love in a Women’s Prison (Rino Di Silvestro, 1974) and breast-obsessed Russ Meyer’s (now considered to be cult classics) romps like Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (with Faster, Pussycat, Faster as the B Movie) in 1970 and the inevitable Supervixens (Russ Meyer, 1975); the haunt of somnambulant drunks sleeping off the evening’s binge and men in raincoats shuffling secretively in the back rows, the floor littered with balled-up tissues that it would be inadvisable to investigate. It is there, far away from the established centres of culture one rainy night, that we stumble over Derek Jarman’s Sebastiane (Paul Humfress & Derek Jarman, 1976) – and queer cinema finally comes of age.

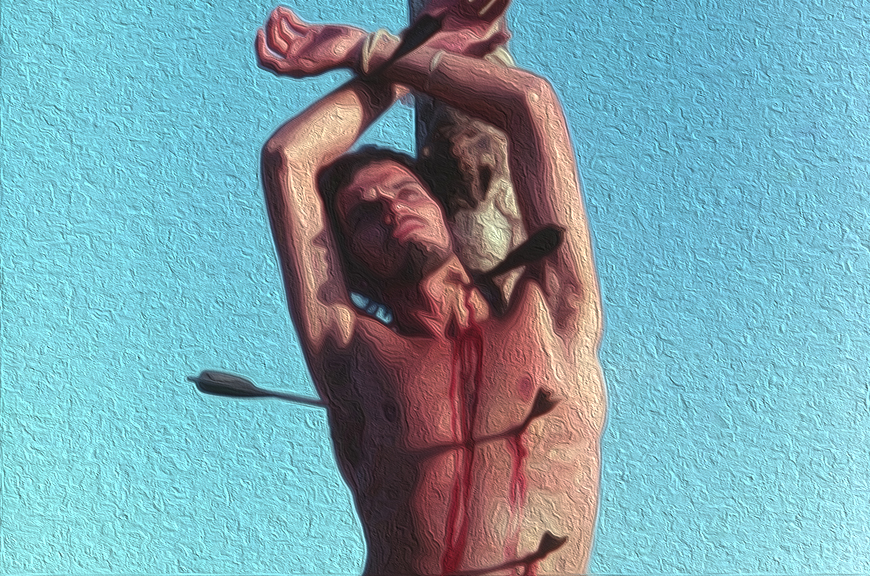

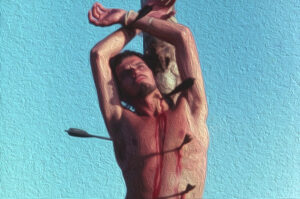

There is no coyness in Sebastian. Though Biblical, the theme is unquestionably homosexual – desire gone bad in a sweltering desert setting. The dialogue is in Latin with English subtitles – “Oedipus”, someone shouts. “Motherfucker”, the subtitle translates. And there are boys, lots and lots of them, all of them bronzed and beautiful, and all of them naked. And I mean naked. Jarman’s camera is unflinching as it worships its subjects, and this is in-your-face male nudity, none of the slightly comic hairy male buttocks that audiences are used to seeing in Timothy Leary Confessions Of… movies at the local Odeon. There are no carefully choreographed pans to avoid genitals, no swerving away from anything that might make an audience uncomfortable – or hot. (When the film was rerun at GFT as B Movie to Jarman’s Jubilee a couple of years later, punks and Glasgow University film society intellectuals alike reeled in sheer incredulity – and horror – at its blatant and unashamed queerness.)

Queer cinema was here. And it was here to stay.

Written for The Film Dispatch by Max Scratchmann.