Ned Wolfe quit his nine-to-five job to pursue comics. Here, the 2012 Design and Digital Media graduate reveals how he uses artefacts and archives to bring authenticity to his graphic projects, including a biography of TE Lawrence.

Degree: MSc Design and Digital Media, 2012

Current treasured object: An amigurumi stuffed fox named Sherston I commissioned from a friend. He sits on my desk as I work.

Song of the moment: ‘Bulletproof Heart’ by My Chemical Romance

The first thing I noticed when I woke up this morning: The soft, cool, winter morning light

The nature of making a comic is like creating a film, except as cartoonist I’m the location scout, costume designer, director, actors, cinematographer, and screenwriter all at once.

When I tell people that I’m a history cartoonist, and that I use material artefacts and archives for my work, I get a lot of questions, most common being, “You can do that?” There’s this air of mystery surrounding archives that feels like an impenetrable fortress that can only be accessed with the right combination of words and perhaps an arcane symbol or two. Prior to my March 2019 research trip to Oxford, I thought the same thing. I was very fortunately proven wrong – though I did have to swear an oath to protect the Bodleian Library.

One of my current projects is a graphic biography of TE Lawrence, immortalized as Lawrence of Arabia thanks to his exploits in Arabia during the First World War. He grew up in Oxford, and attended university there, and a number of his personal papers are held in the Bodleian Library. In addition to my archive consultation, I timed my visit to attend an exhibition about Lawrence held at Magdalen College.

The nature of making a comic is like creating a film, except as cartoonist I’m the location scout, costume designer, director, actors, cinematographer, and screenwriter all at once. While some elements, like writing the script, can be done largely from home utilising readily available books, the more visual elements require an additional level of research. Looking at photographs and physical objects from the era help make the world more real to the artist – and as a result, to the audience as well.

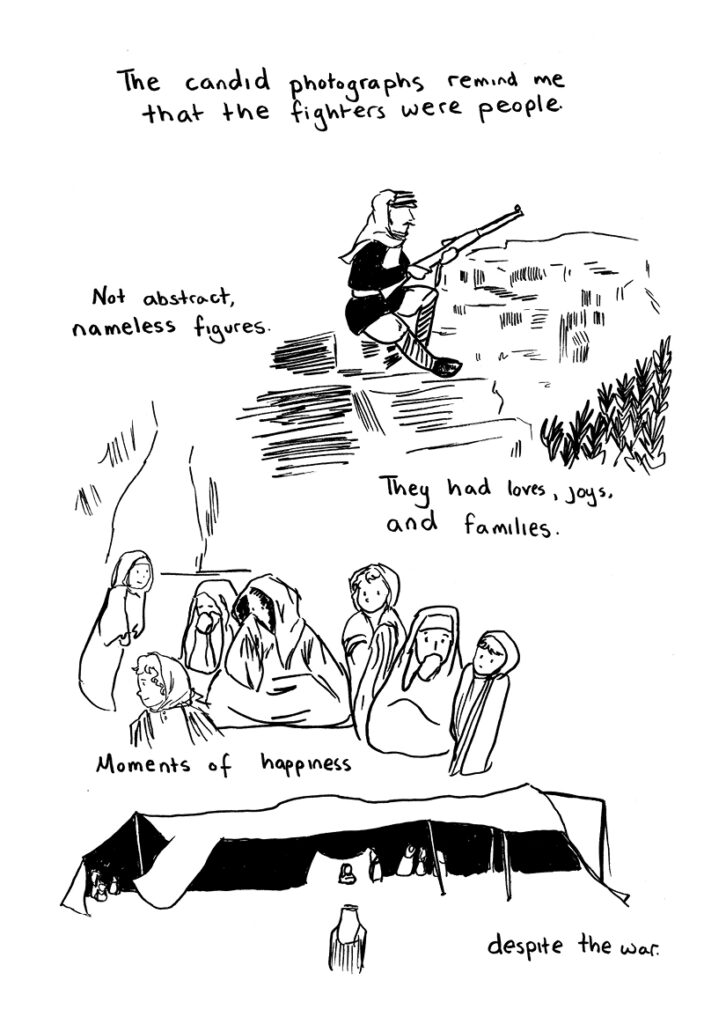

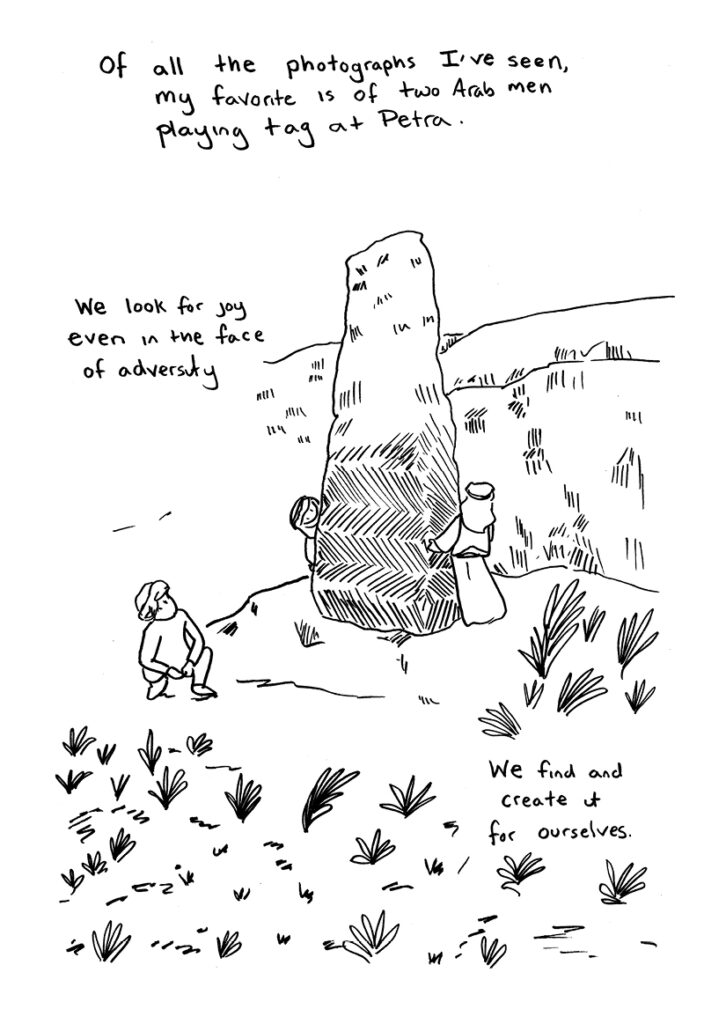

What I was most excited about seeing in Lawrence’s archives were his photographs. Lawrence was a keen amateur photographer, and carried a camera with him through much of his travels. Where comics are a visual medium, photographs and illustrations are key for creating a believable, authentic world for readers. I cherish these as much as written primary sources. The photographs are especially wonderful for the faces of the Arab men Lawrence worked beside as both archaeologist and soldier. I’m struck by the mundanity of the activities they show – from daily work, to relaxing and having fun.

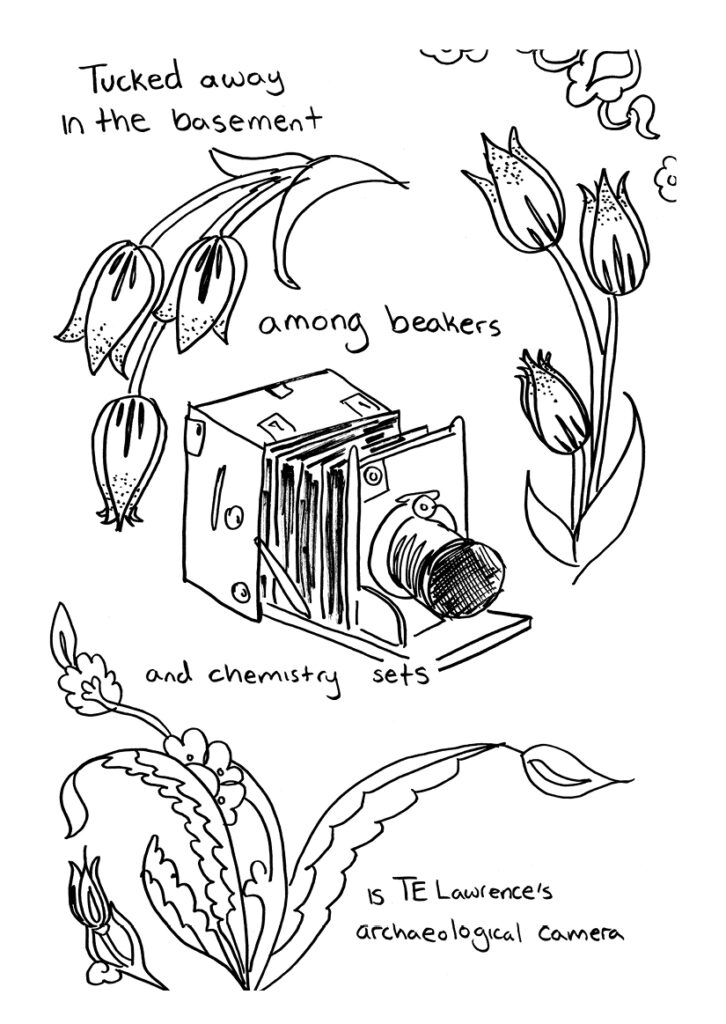

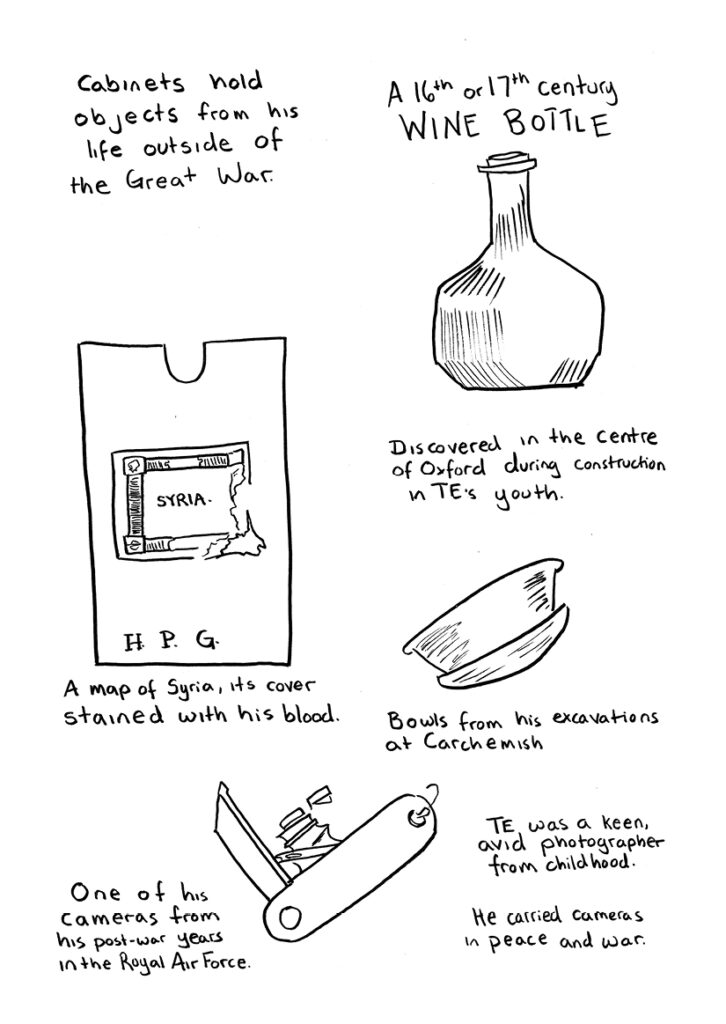

What I was not expecting was the wonderful material objects on display at Magdalen College, as well as throughout Oxford itself. The objects were varied – from bowls and books and personal effects on display as part of the Lawrence of Oxford exhibition, to Lawrence’s stunning robes and archaeological artefacts at the Ashmolean, to what ended up being the biggest surprise of my trip. I hadn’t known that Lawrence’s archaeological camera was on display at the Museum of the History of Science until I visited the exhibition, and added an extra stop.

Being able to see and interact with objects someone used and owned is magnificent. Even if I can’t touch the things, I can observe and sketch and see how they were used. This is really why I love archives and material artefacts. There’s a real weight to them, both physically and metaphorically, to encounter objects that were loved and cherished. They are what remains of how Lawrence lived his life – from his motorcycle insurance to favourite books.

As a history cartoonist, I accept that I may not write the great biography that changes our understanding of Lawrence. What I can do is tell an engaging story with respect for those who were involved. My books could end up being someone’s first or only exposure to TE Lawrence, and I want to make sure it is an authentic portrayal of his life. I say ‘authentic’ over ‘accurate’ to reflect that my work is ultimately subjective. I can’t sit down and interview Lawrence and his comrades and contemporaries. I can read their letters, memos and memoirs, and recreate their relationships from there. I aim for thematic authenticity over exact accuracy because the latter is impossible. And archives and artefacts help me do just that.

(Selected illustrations from ‘Dreamers of the Day’, a graphic biography of TE Lawrence.)