Professor Raj Bhopal on why ethnic and racial minority groups are seemingly being disproportionately affected by COVID-19.

My name is Raj Bhopal and I am Emeritus Professor of Public Health at the Usher Institute. I officially retired in 2018, having held the John Usher Chair of Public Health for 19 years.

My name is Raj Bhopal and I am Emeritus Professor of Public Health at the Usher Institute. I officially retired in 2018, having held the John Usher Chair of Public Health for 19 years.

I have devoted much of my academic career to studying public health epidemiology with special reference to ethnic and racial variations in health and healthcare outcomes. I have, for example, been studying for 35 years the approximately 1.5 and three-fold increased incidence of heart disease and diabetes, respectively, among Asians.

Now the Covid-19 pandemic has brought me out of retirement and I have been working with colleagues including Dr Gwenetta Curry to review why ethnic and racial minority groups are seemingly being disproportionately affected by this virus. Our work is focussed on UK South Asian and Black (African origin) and African-American populations.

Inequalities

The pandemic has sharpened the focus on structural and societal inequalities that have long existed in the UK, the USA, and other countries. In our view, the ethnic variations we’re seeing in hospitalisations and death is largely due to socioeconomic and environmental factors, rather than biological explanations.

For example, many people from minority ethnic groups, especially those who are also recent migrants, hold essential jobs in health and social care, retail, public transport, and other sectors, putting them on the front line and at risk of exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Ethnic and migrant minority groups are more likely to live in overcrowded urban housing centres, the conditions of which can make physical distancing and self-isolation difficult.

Me and my son Dr Sunil Bhopal

Health disparities

We know that chronic conditions, especially diabetes, are more common in migrant and ethnic minority groups in Europe and the USA. These co-morbidities are contributing to comparatively adverse outcomes for those people who develop COVID-19.

Healthcare disparities are also likely to have a role. For example, in the USA, Black or African American minorities and Hispanic groups are less likely to have health insurance, with consequent reduced health-care access and use.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)31102-8/fulltext

What can we do?

We urgently need political action to tackle xenophobia, systemic racism, and individual level prejudice and discrimination with concerted efforts to resolve long-standing societal inequalities globally.

I have been contributing to many papers and articles and working with fellow academics and the media to raise awareness of these issues.

Recently, I informed MPs and the BBC about the existence of a report that was denied by ministers in Parliament. This information persuaded the UK Government to release the report containing vital recommendations of measures to protect ethnic minority groups during the pandemic.

I am particularly concerned about the worldwide impact of COVID-19 on immigrant populations, specifically failed asylum seekers and undocumented immigrants. Equally, failing to attend to such populations is a risk to all of us. This was demonstrated recently in Singapore, where the pandemic was controlled except in the hostels housing migrants. This led to a second wave of infections emerging from these hostels.

I have written to the UK and devolved governments to urge them to remove the ‘no recourse to public funds’ condition, which prevents people who don’t have permanent leave to remain in the UK from accessing state benefits.

Many of these individuals contribute significantly to frontline public services, such as the NHS, and fulfill key-worker positions maintaining the nation’s infrastructure, cleanliness and sustenance supplies. Yet these workers do not have access to the same state rights and support as their friends, neighbours and colleagues. This includes rights such as child tax credit for those in employment and for those who have lost their jobs due to COVID-19, who were already engaged in precarious self- or zero-hour contract employment. There is no safety net or furloughing or state support.

I believe this is an unjustifiable denial of the human rights of some workers, students and others, who are not being treated on an equal basis with other citizens as a result of their nationality. This is particularly egregious at a time of national crisis, such as we are facing right now.

https://www.bmj.com/content/368/bmj.m1213/rapid-responses

Children from the carefree days we now yearn for.

Effects on children and young people

Another major concern of mine is the impact of the pandemic on babies, children and young people across health, education, social care, justice and poverty. With my son Sunil, a a lecturer and specialist trainee in paediatrics, I am helping to set out the risks of COVID-19 in children in the context of other problems we have. We have found that less than 0.4% of deaths in children are caused by COVID-19, fewer than by influenza and road traffic accidents. The bottom line for me is that my children and grandchildren are far more important than I am. I don’t want them to be disadvantaged to try and prevent me getting COVID-19.

The different policies of European countries, and indeed even within the UK, in relation to children returning to school are an example of confusing variability that could have major impact on the future livelihoods of our children.

To help provide some context for parents, teachers, clinicians and policymakers grappling with this, we have examined age-specific mortality data across several countries which shows that deaths from COVID-19 fortunately remain very infrequent in children and young people. Results are similar for each country.

We are making this data freely available through a table published online, which includes deaths by age-categories and by country and is regularly updated with the latest data (https://tinyurl.com/child-covid) .

Given these data, we think the medical community should be upfront with parents, carers, teachers, clinicians and decision-makers that the direct impact of COVID-19 on children is currently small in comparison with other risks that children face in everyday life, and that the main reason we are keeping children at home is to protect adults. This conclusion may change as the pandemic evolves, and the epidemiology of COVID-19 in children should be closely monitored.

https://www.bmj.com/content/369/bmj.m1669/rr-4

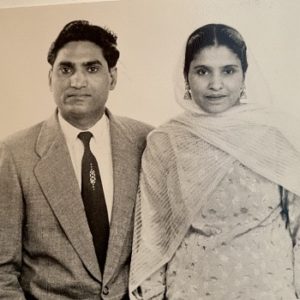

My parents shortly after arriving in UK.

A bit about me

Many of us who come from abroad have unusual histories and I would certainly say this about my own family. I was born in Moga, a town in Punjab in the fifties and we moved to the Gorbals, Glasgow when I was two years old. The Gorbals was the most notorious slum in the whole of Europe. Many immigrants in Scotland started their lives there.

My mother’s side of the family were in the tailoring business that supplied uniforms for the British army in India. My father was also a tailor. A few years after arriving and saving some money in Glasgow, my father started a wholesale and retail clothing shop called Moga Trading Company in Norfolk Street, which was on the A1 leading from Glasgow to London. I would consider myself both Punjabi and Scottish in a 50-50 ratio but I didn’t become a tailor. Like many traditional Indian families, we were all encouraged to become professionals and I became a doctor.

Related titles by Professor Raj Bhopal

>> Migration, Ethnicity, Race, and Health in Multicultural Societies

>> Epidemic of Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes

Blog written by Professor Raj Bhopal and edited by J Middleton and J Durkin

Dr C R Gillespie

Dear Raj,

Thank you for this brilliant paper and the clear insights for children with their very low risk of death by C19. Have you estimated the risk of transmission to a more vulnerable population, parents and grand parents who may live with them?