Strategy of Archive Collection

Our list of archives that make up the exhibition’s display.

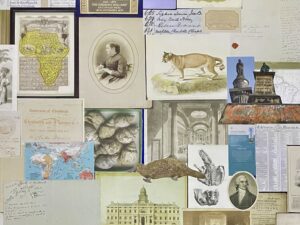

Much of our display material consists of collections and archives from the Centre for Research Collections and the University’s Art collection, and in the face of a vast library of images, we have meticulously selected those for display based on their relevance and representativeness to our narrative threads: the Edinburgh Seven, Edmonstone, the Old College building, Specimens, and the Natural History Museum. However, archive collection management and development strategies are highly context dependent. An arts education perspective attuned to social justice is indispensable here, confronting the enduring questions of what to preserve, what to exclude, and the implications of these choices on historical access and narrative. These queries revolve around what materials to preserve, who should undertake the collection, where these materials belong, who is represented, and in what manner.[1] This approach, where institutions introspectively research their archive collections, promotes a sustainable and deeply impactful engagement with the gallery’s past for our exhibition program..

Depth and Breadth

Large national institutions have adopted more educational and societal recording responsibilities, developing archival departments to ensure the preservation, organization, and description of archival materials. These departments create secure environments, fostering the longevity and utility of archives.[2]

The National Galleries of Scotland emphasize the depth of time in preserving collections. For instance, Kirsten Dunne, the Senior Projects Conservator, employs microfading and advanced conservation technology to safeguard archives for an ambitious span of 500 years. In contrast, the National Library of Scotland prioritizes the breadth of its collections. It actively gathers records of cultural events from minor communities, including a diverse range of materials from posters to digital archives like Minecraft and Archive of Our Own. The exhibition Blood, sweat and tears: Scotland’s HIV story (2023) is an exemplary display that honors activists, healthcare workers, and those affected by HIV and AIDS through a collection of arts and crafts, health and fundraising leaflets, and newspapers reflecting societal attitudes.[3] This community collecting effort aligns with their new “Reaching People” strategy and includes partnerships with research institutions and community organizations.[4]

Independence

The J. Paul Getty Trust’s Institutional Archives stands as a model of independent collection strategy, documenting its extensive activities as an international cultural and philanthropic organization in the visual arts. The Trust’s archival collection includes records from past and present administrations and programs, covering the Museum, the Conservation Institute, the Education Institute, the Information Institute, the Leadership Institute, the Research Institute, and the Getty Foundation.[5] Accessible to the public are administrative records, documents detailing external collaborations, public programming documentation, construction records for the Getty Center and the Getty Villa, media coverage, as well as J. Paul Getty’s personal papers and oral histories from artists, historians, and Getty staff.[6]

The strategy of Contemporary Gallery Institutional to Archive Gaps

How do we respond to the lack of contemporary gallery institutional archives? To this day, cultural institutions face vacancies in archives. The Fruitmarket Gallery illustrates an active effort to encompass every facet by constructing its archival network. Following its redevelopment in 2021, The Fruitmarket Gallery inaugurated a dedicated room for holding physical archival materials onsite, providing a space for in-depth study.[7] These materials, while not a complete chronicle of exhibition history, have withstood challenges of dampness, fire, and bouts of institutional neglect. Although the Fruitmarket was established in 1974, the materials retained date back to the commencement of Mark Francis’s directorship in 1984.[8]

This collection encompasses curatorial notes, press releases, clippings, leaflets, posters, slides, photographs, and the like.[9] According to the conversation we had with Ruth Bretherick, Research and Public Engagement Curator Fruit Market Gallery during an Archive visit, The Fruitmarket Gallery keeping an ongoing cataloguing process, constantly discovering things and buying back their early-stage publication. Moreover, she has offered an alternative for those seeking archives by directing them to established public institutions like the National Library of Scotland. This strategy not only leverages the comprehensive scope and depth of national institutions but also allows the gallery itself to allocate more budget and space for developing an independent institutional archive—a curatorial library in its own right.

The Talbot Rice Gallery’s space history as the Natural History Museum, its’ collections built up by the Museum’s chairman, Professor Jameson, using his network of contacts to the extent that it could not be properly collected, has had to survive in a damp environment and transferred to the National Museum of Scotland at 1975.[10] Until now, the Talbot Rice Gallery has been a gallery without an archive or collections department, and we needed the National Library of Scotland to find most of the material from previous exhibitions, which is an interesting shift. Our exhibitions can be meaningful documents of the space’s past and present. Emulating the Fruitmarket’s archival network, our display citations serve as a navigational tool for visitors, particularly artists and researchers, to explore the extensive holdings within the Centre for Research Collections, the National Museum of Scotland and the University Art Collection. This approach and our exhibition programming archive workshop also enhances the visibility of the internal university institutions such as the Centre for Research Collections, broadening awareness of the collection and encouraging future scholarly engagement.

Our project aims that provide resources for further Talbot Rice Gallery’s residency artists to do their creation, showing it can be a foundation of the practice of another individual archival strategy- artists as archivists. This role extends beyond the traditional image of the artist-as-curator, with artists now engaging directly with the curation of collections. Yet, their focus shifts away from critiquing representational completeness or institutional integrity to a more personal and direct involvement with the archival process. [11]

[1] Ann Holt, ‘An In(Ex)Clusive World: Towards “Participatory” Archives Practices in Art Education’, in Bridging Communities through Socially Engaged Art (Routledge, 2019).

[2] Gregory S. Hunter, Developing and Maintaining Practical Archives : A How-to-Do-It Manual (New York : Neal-Schuman Publishers, 2003), http://archive.org/details/developingmainta0000hunt.

[3] ‘Blood Sweat and Tears’, National Library of Scotland, accessed 29 April 2024, https://www.nls.uk/exhibitions/blood-sweat-and-tears/.

[4] ‘General Collections Direction of Travel 2021-25 Extract for Community Seminar’ (National Library of Scotland, 2024).

[5] ‘Institutional Archives (Getty Research Institute)’, 5 December 2023, https://www.getty.edu/research/special_collections/institutional_archives/.

[6] Ibid.

[7] ‘Archive Archive’, Fruitmarket, accessed 29 April 2024, https://www.fruitmarket.co.uk/archive/.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Andrew G. Fraser, The Building of Old College: Adam, Playfair & the University of Edinburgh / Andrew G. Fraser. (Edinburgh: University Press, 1989), 196.

[11] Hal Foster, ‘An Archival Impulse’, October 110 (2004): 3–22, https://doi.org/10.1162/0162287042379847.