As an international student, my knowledge of Western history had not covered the Enlightenment’s influence until I investigated the story of the puma. Research into this period, how animals and commodities like sugar and rum were transferred as part of the slave trade reveals the colonial discourse of the era to me.

In tracing the journey of platypus’s connection, it was sent by a navy Sir Thomas Brisbane, then governor of New South Wales, I discovered parallel stories.[1] The puma arrived in Edinburgh in 1827 by William John Napier, a British naval officer associated with the Royal Society of Edinburgh.[2] Both Brisbane and Napier, alongside figures like Jameson, played roles in shaping the city’s intellectual narrative.[3][4]

It is quite surprising that this historical pattern also intersected with my Chinese background. William John Napier, who served as the Chief Super Intendent of Trade at Canton (Guangzhou, China), was central to the Napier Affair.[5] His unsuccessful bid to negotiate unsanctioned trade in China in 1834, which halted trade and heightened Anglo-Chinese tensions, unwittingly laid the groundwork for the First Opium War.[6]

Different sized figures in our final display.

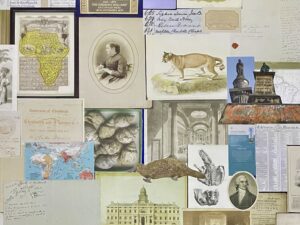

Within Old College, we sought to give voice to the underrepresented stories through our exhibition, enlarging images of animals and women impacted by colonization while diminishing those figures who benefited from it. This visual approach not only rectified historical imbalances, but also prompted a critical reassessment of how the Natural History Museum was like a monster and swallowed everything it could reach.[7]

Today, institutions like the Hunterian Museum use their spaces to dissect the evolution of knowledge and the complex web of relations between local and global contexts.[8] This historical contemplation has broadened my perspective of Old College, transforming it from an isolated architectural piece into a nexus of global connections. It encourages me to extend my research beyond my cultural identity, unearthing the complex layers that comprise its narrative.

[1] Bill Jenkins, ‘The Platypus in Edinburgh: Robert Jameson, Robert Knox and the Place of the Ornithorhynchus in Nature, 1821–24’, Annals of Science 73, no. 4 (1 October 2016): 432, https://doi.org/10.1080/00033790.2016.1230783.

[2] ‘William Napier, 9th Lord Napier’, in Wikipedia, 9 March 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=William_Napier,_9th_Lord_Napier&oldid=1212756424.

[3] ‘Thomas Brisbane’, in Wikipedia, 1 April 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Thomas_Brisbane&oldid=1216747653.

[4] ‘William Napier, 9th Lord Napier’.

[5] ibid.

[6] ‘China & Trade with the West: The Napier Affair (1834)’, 28 September 2007, https://www.schaab-hanke.de/lehrveranstaltungen/SS2003/texte/ob35.html.

[7] W. J. T. (William John Thomas) Mitchell, ‘Museums and Other Monsters’ (conference of Municipal Museums, Florence, Italy, 2019).

[8] ‘The Hunterian’, accessed 28 April 2024, https://www.gla.ac.uk/hunterian/visit/ourvenues/hunterianmuseum/.

Leave a Reply