Putting Outdoor Learning in its Place: A Resource to Aide the Development of Place-Based Outdoor Learning Pedagogy in Scottish Primary Education

About the author

Stewart Atkinson is an active and enthusiastic facilitator of outdoor learning experiences. He graduated with merit from the Outdoor Education MSc programme having been accepted onto the course with no prior academic experience, relying instead on his sector experience. Having worked in independent education, local-authorities and third sector organisations, his MSc has helped him start his own outdoor learning consultancy company; “OutdoorClassrooms.Scot Ltd”.

Through OutdoorClassrooms.Scot he hopes to use the resource he created in addition to the experience and knowledge he gained to enable more facilitators engage in place-based outdoor learning in their own settings. For further information regarding his applied research project, to talk about future projects or just for a friendly chat about anything outdoors related please contact him via email: info@outdoorclassrooms.scot or check out twitter @OutClassScot Facebook: OutdoorClassrooms.Scot or Instagram: @OutdoorClassrooms.Scot

Through OutdoorClassrooms.Scot he hopes to use the resource he created in addition to the experience and knowledge he gained to enable more facilitators engage in place-based outdoor learning in their own settings. For further information regarding his applied research project, to talk about future projects or just for a friendly chat about anything outdoors related please contact him via email: info@outdoorclassrooms.scot or check out twitter @OutClassScot Facebook: OutdoorClassrooms.Scot or Instagram: @OutdoorClassrooms.Scot

Disconnection with place

I was fortunate enough to attend residential outdoor education field trips when I was in school. Perhaps that was what laid the foundations for a career of 15 years (and counting) that I am truly passionate about. Having spent 5 years working in the sister centre of the one I visited as a child, I began reflecting on how isolated these experiences, so far from home, could be if not carefully planned.

I am a huge advocate for residential outdoor learning and I wholeheartedly agree with the work going into the proposal for a Bill to ensure that all young people have the opportunity to experience residential outdoor education. However, I also believe strongly that these experiences should not be seen as a tick in the box, standalone exercise with a drag and drop approach paying no attention to place, and with little regard for curriculum which is authentic to the individual.

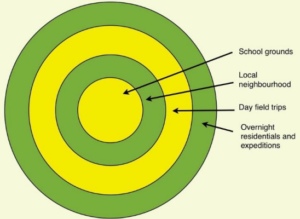

When the time came for me to complete my dissertation, I wanted to engage in something I was truly passionate about and in a way that I felt I could make a difference. After many conversations with visiting staff in a residential outdoor learning setting and having connected with “the four zones of outdoor learning” (Beames et al., 2012, p. 6) which was adapted from Higgins and Nicol (2002, p. 44). I realised that more support was needed in the two innermost zones of outdoor learning: the “school grounds” and “local neighbourhood”.

By supporting practitioners in this area, we can not only augment classroom-based learning, but also enhance outdoor learning in the outermost zones (“Day excursions” and “Overnight stays, residentials and expeditions).

Applied Research Project

I wanted my research to address this lack of support and I wanted it to be based on authentic learning within a school community while remaining accessible to all within it.

I embedded myself within a school community for 5 months and conducted a literature review to find out what the barriers really were. It was at this point that my supervisor suggested I choose an “applied research project”. Part A investigates and provides justification for Part B, a resource. It verified the hypothesis that several barriers to outdoor learning provision do exist. It then presents the pedagogical argument that place-based outdoor learning addresses these barriers and justifies the approach and decision making behind the resource’s structure, style and support requirements.

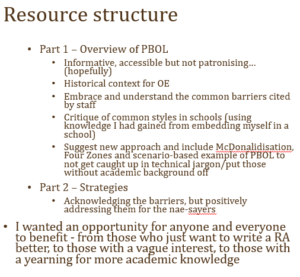

Part B is a booklet that includes the background, barriers, required support, strategies, guidance and further signposting that can be used within an educational setting to foster a sustainable culture of place-based outdoor learning in a school community.

Key factors in creating the resource

Action research has been criticised for a lack of robustness in comparison to other research methods (Somekh, 2006). However, it’s aims to elicit change at a local level and break the culture of “ivory tower research” (Munn-Giddings, 2012, p. 71) held a certain resonance in my own experience as a practitioner. Therefore, the resource has been informed by literature to a high degree which is critiqued in part A. Yet, the perceived unobtainable nature of academic knowledge has not permeated into the resource (Part B) as to make it inaccessible to a non-academic reader and therefore not useful to school communities.

The drag and drop approach to outdoor learning (Lloyd, Truong, & Gray, 2018) that some organisations adopt can disentangle the individual from any experience that might otherwise incorporate the community or place. As commercial outdoor learning enterprises grow, there is potential for under-theorised practice and social ambivalence. This is critiqued by not only Lloyd at al. but also Mark Leather (2018) in his discussions on McDonaldization. I included this as a concept in a simplified manner in Part B to signpost the practitioner away from and critique an otherwise common approach.

My structure was simple; After a brief discussion of outdoor learning in a historical context, critiquing common approaches while recognising common barriers in an informative, accessible but not patronising manner, my resource suggested that a place-based approach could not only overcome these barriers, but enhance practice.

My structure was simple; After a brief discussion of outdoor learning in a historical context, critiquing common approaches while recognising common barriers in an informative, accessible but not patronising manner, my resource suggested that a place-based approach could not only overcome these barriers, but enhance practice.

However, I also wanted facilitators and their young people to be able to pick up this resource and immediately benefit, without investing entirely in the whole 40-page document. I hoped that this could provide the necessary motivation for further reading, research or signposting if time was a barrier to that individual.

How has it influenced my practice?

I embedded myself in one school to attempt to understand the need for my applied project. In doing so I realised that a place-centric approach to outdoor learning truly has to be individualised. Not only in terms of the experiences facilitated, but also when recognising the individual barriers to its development and sustainability. Every learner is different, as is every facilitator, place, school and community. Therefore, a deliberately different approach must be taken to each attempt to facilitate experiences outdoors and create connections and encourage the stability that places can give in an otherwise unstable world.

I embedded myself in one school to attempt to understand the need for my applied project. In doing so I realised that a place-centric approach to outdoor learning truly has to be individualised. Not only in terms of the experiences facilitated, but also when recognising the individual barriers to its development and sustainability. Every learner is different, as is every facilitator, place, school and community. Therefore, a deliberately different approach must be taken to each attempt to facilitate experiences outdoors and create connections and encourage the stability that places can give in an otherwise unstable world.

Comments are closed

Comments to this thread have been closed by the post author or by an administrator.