Alasdair MacIntyre (2001) ‘Catholic Universities: Dangers, Hopes, Choices’, in Robert E. Sullivan (ed.) Higher Learning and Catholic Traditions. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, pp. 1–21.

While the essay is most obviously about Catholic universities, MacIntyre makes clear that all universities can learn from some of the Catholic writers who have written about the university.

Alasdair MacIntyre explicitly states that the integrative task – synthesising specialized disciplines into a coherent understanding of reality – is not exclusively Catholic, but a requirement for any institution to function as a true university, regardless of religious identity. MacIntyre argues that Catholic universities must prioritise an integrative task – synthesising specialised disciplines into a unified understanding of the order of things – to remain true universities, not fragmented assemblages of narrow expertise. Drawing on John Henry Newman and Pope John Paul II, he warns that modern American research universities risk failure by abandoning this synthesis, a danger Catholic institutions can counter through philosophy, theology, and liberal arts, while resisting secular drift, compartmentalisation, and vocational reductionism.

—

1. The Integrative Tasks of a Catholic University

Universities fail when they treat disciplines as isolated silos rather than contributions to holistic understanding. Newman defines true enlargement of mind as ‘the power of viewing many things at once as one whole, of referring them severally to their true place in the universal system’ (page 2). John Paul II echoes this: scholars must ‘determine the relative place and meaning of each of the various disciplines within the context of a vision of the human person and the world’ (page 2).

Educated minds exhibit:

- Surprise and perplexity: Recognising ignorance and astonishment at the world.

- Cross-disciplinary application: Bringing diverse findings to bear on complex questions (e.g., earthquakes requiring geology, history, and ethics).

- Contextual flourishing: Situating phenomena within a structured order where lower levels (e.g., subatomic particles) enable and constrain higher ones (e.g., human societies).

Philosophy handles secular integration; theology adds revelation’s corrective lens. The ideal curriculum mandates philosophy and theology for all students, plus specialised disciplines and foundational skills. Modern threats include not rival ideologies but fragmentation – treating knowledge as disconnected sub-disciplines, turning undergraduates into pre-graduate school prep and graduate school into narrow training.

A key test: Would a university tenure a brilliant integrative teacher over a cutting-edge specialist? If the specialist wins, ‘that university is in need of radical reform’ (page 6). Philosophy must reclaim its sapiential dimension (John Paul II) as the ‘ultimate framework of the unity of human knowledge’ (page 7); theology must illuminate nature through grace, requiring philosophers to be theologians and vice versa.

—

2. Two Alternative Directions for Catholic Universities

Catholic universities face a spectrum:

- Traditional model: Philosophy and theology integrate all enquiry; Catholic faculty predominate; accountability to the Church (especially in theology) ensures identity. John Paul II calls Aquinas a ‘master of thought’ (page 11), mandating systematic dialogue with him.

- Secular-add-on model: A standard research university with Catholic practices superadded; evaluation by disciplinary standards only; no privileged integrative role.

Movement toward fragmentation happens by drift unless countered; deliberate planning is needed for integration. Hiring faculty aimed at secular prestige yields ‘a significantly inferior replica’ (page 12) of those universities, eroding Catholic distinctiveness.

—

3. Education for Making Choices

Undergraduate education should focus on liberal arts and sciences (including natural sciences) valued for their own sake, liberating minds from cultural preconceptions.

Stages:

- Master basic skills (clarity, precision).

- Inhabit alien standpoints (e.g., Giotto, Dante, Aquinas).

- Recognise diverse human goods for informed choices.

Dangers:

- Students view education as job training for ‘making a good deal of money, being in a position of personal power’ (page 16, from the Howard R Greene survey).

- Universities treat students as consumers, reinforcing premature choices.

Compartmentalisation dissolves individuals into roles (home, work, chapel) with no unifying critique. Catholic education must provide milieus for whole-life evaluation, integrating classroom, chapel, athletics, and social life. Faculty must converse across disciplines; curriculum committees should force mutual justification.

—

4. Whose Choices?

Faculty, not administrators, determine direction through daily decisions. Administrators must remain active teachers to avoid top-down imposition. Inertia leads to secular assimilation; hope lies in recognizing the choice and acting deliberately.

MacIntyre concludes on a note of guarded optimism: awareness of danger is the first step toward renewal, preserving Catholic universities as genuine universities ordered toward truth, human flourishing, and God.

—

A couple of immediate questions raised by this essay for universities, including secular ones:

- Can universities – secular or Catholic – convince students, parents, and employers that higher education is not merely job training, especially given high tuition, student debt, and a culture that equates degrees with economic return?

- MacIntyre (2012, p. 15) argues a university must be deliberately ‘unresponsive‘, giving students what they ‘need,’ not what they ‘want,’ until the two align. In secular universities that have often replaced needs-based curriculum design with catering to student preferences, how can institutions reclaim formative authority that overrides expressed wants in pursuit of genuine intellectual goods?

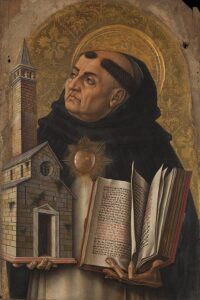

(Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Notre Dame University, Indiana)