Alasdair MacIntyre (2006). The end of education: the fragmentation of the American university. Commonweal, 133: 18.

In this short article about the American Catholic university, MacIntyre makes several claims about both Catholic and secular institutions in the USA. Perhaps the most provocative is in the opening statement: from a Catholic point of view, the contemporary secular university is not at fault for being non-Catholic, but for failing to be a university at all.

What does he mean? He argues that the modern secular university has gone wrong in three ways:

- The continual multiplication of disciplines, subdisciplines, and sub‑subdisciplines.

- The increasing specialisation of academics, who have been transformed into professionalised, narrowly focused researchers who happen also to teach.

- The resulting distortion of students’ education:

- Undergraduates now focus primarily on gaining the specialised knowledge required for advanced study, making the first degree merely a prelude to graduate school.

- Students must make early and largely irrevocable decisions about their studies, despite not knowing what they really need to learn.

- The curriculum becomes a fragmented assortment of courses – some highly specialised, others introductory – with no one responsible for making connections between them.

At the heart of this crisis, MacIntyre identifies a lacuna: the modern secular university lacks any coherent conception of human nature or the human condition. Different disciplines teach about human nature and the human condition, but in isolation from one another.

To remedy this, he proposes a tripartite curriculum for the educated generalist:

- Mathematical and scientific studies,

- Historical studies (social, political, economic),

- Linguistic and literary studies.

This broadening of the curriculum, however, is not enough. The faculty must also be committed to the curriculum as a whole, and to pursuing questions that matter across disciplines. Without this, students will continue to leave university with fragmented knowledge and no understanding of how it relates to the larger questions about human nature and society.

MacIntyre argues that today we lack an educated public – one with shared standards of argument and inquiry and a common sense of the central questions that must be addressed. Such a public, he suggests, would be less susceptible to partisan distortion and shallow debate.

At the end of the article, MacIntyre turns to the Catholic university specifically. He reminds us that Newman proposed theology as the integrative discipline that gives coherence to a university. Catholic theology, in addressing questions of human nature and the human condition, can model a way of grappling with such questions – not just as abstract inquiries but as questions with practical significance for how we live.

He concedes that specialisation has its place – for example, in a final year devoted to research or professional training – but insists that the bulk of an undergraduate degree must be a liberal education in the arts and sciences, one that prepares students to ask and understand the questions that matter. In short, the goal is not to eliminate specialisation, but to locate it within a broader, more coherent understanding of knowledge and its role in shaping human life.

Link to article: https://www.proquest.com/magazines/end-education/docview/210402472/se-2?accountid=10673

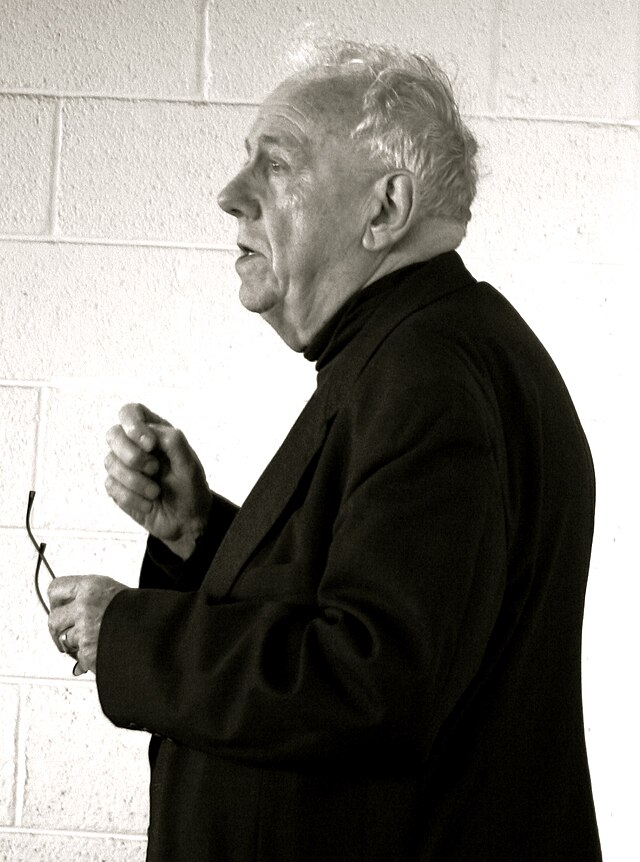

(Alasdair MacIntyre at The International Society for MacIntyrean Enquiry conference held at the University College Dublin, March 9, 2009.)