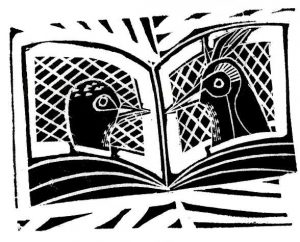

One of eight illustrations for The Lumber Room, by Saki

I

A MURDER OF CROWS

Current research involves Illustration’s collaborative relationship with writers, editors, publishers, designers and artists. This embraces academic and professional contexts to be explored in studio pieces and commissioned work. This research also involves the ECA Drawing Book, Shaping the View and the Picture Hooks projects. These are collaborative works in and beyond ECA, involving current ECA students, staff, and alumni.

The history of Illustration is inextricably connected to histories of printing, design, technology and book publishing, as well as Art. Its greatest exponents, past & present, have engaged with literary content and formats of the page and in fundamental relationships of imagery to the written word.

For the purpose of Lines today, my starting point is the subject of birds.

This begins with a currently commissioned piece for the Random Spectacular magazine, designed and edited by Simon Lewin in Edinburgh. The illustration interprets The Lumber Room, the short story by Saki, (H.H. Munro). This is a complex, multi-faceted storyline of time & space.

In addition to a full-page image, there are seven spot illustrations, interspersed within the text to enhance the typographic layout. These minature images give visual punctuation to the narrative and alter the reader’s pace in following passages of text within the architecture of the page.

An Ibis, for example, sits amongst a treasure trove of objects with other nameless birds. All of these have decorative and symbolic roles within the composition. To an extent, the identity of an illustration is defined by its context although the image may have validity in its own right, with intellectual and artistic integrity beyond the published context. However, I suggest that it is impossible to understand and appreciate the illustrations without their textual accompaniments.

In one section is an illustration of an illustration. Two birds communicate, beak to beak, across the gutter of an open book, and they extend outside its frame. There is a play upon image within image and frames within a frame; a pictorial device used in many of illustrations, paintings and drawings.

The Lumber Room birds can be compared to The Nightingale, seen In another published context, who sings out of her frame. The placement of this piece is within an editorial page-design, and the bird is framed in a box as a pictorial enclosure. This frame sets off the subject; presenting it to the viewer as if captured.

Illustrations are static, but they may imply or evoke movement.

The Nightingale is in illustration for John Clare’s poem, but is used in the context of a BBC Wildlife Magazine essay about bird-song. It is placed alongside a lark, thrush, and cuckoo; all of which have notable songs.Similarly the Robert Frost illustrations employ frames within frames, with the typographic structure with an underlying grid-structure complementing the graphic character of the illustrations. These are illustrations for poetry. In this book, the Thrush, illustrated for ‘Come In’, also sings out of her box on the page. She is like a toy, or a caged bird. The ‘box’ is a visual device, like a picture frame, or a cell.

Looking at the image away from the page gives a portrayal of the bird, with a title. Reading of the poem, essay, or the short story gives a particular perception of the illustration; the one casting light upon the other, and vice versa.Returning to the Lumber Room, there is juxtaposition of pictorial content, in sections, all of which constitute a sense of the whole.

The illustration pictures the story, but within an abstracted composition.

Various artists have illustrated Saki’s short stories since their publication between 1910 and 1923. I am just another of these, in a long line of interpretations. Saki’s last words spoken in the trenches, just before his death by a sniper’s bullet in World War I:

‘Put that bloody cigarette out!’

Birds populate our world, cityscape and landscape. For some reason, they play a role in much of my illustration work, both to commission and in the studio.

My pictorial treatment of them appears to be repetitive & stylistically similar. However, their varied literary contexts give different aspects of meaning.

The lines in these bird illustrations are engraved into end-grain woodblocks, and imprinted on to paper with letterpress ink. A drawn line necessitates the movement of the whole body, with its focal energy impressed between forefinger and thumb. This is a gesture, a movement of the body, a muscular impulse of shoulder, arm and hand. Drawings are frequently described as ‘gestural’, in some or other mode of artistic representation. The act of drawing is a sequence of movements, coordinated by the mind’s eye & hand to compose an image. This is just one of the ways of defining drawing.

In these engraved lines, they are lines of absence. The un-sculpted areas of the woodblock receive ink to be impressed onto paper. All that is carved away reads as a negative, white line, texture or shape.

Some of these examples are cited in preparation for two group exhibitions in the summer of 2016. They are also pertinent to the forthcoming ECA Illustration Symposium in November: Shaping the View.

One of seven illustrations for The Baite, by John Donne

Jonathan Gibbs 3.V.2016