The complexity of lichens and their forms

This is the audio for this halt. The text below is a transcription of the audio! The audios do not contain all the content written in the text to keep the audios engaging. If you want to have more details, check out the text. Enjoy!

Have you found the tree we will be looking at? Check the tree highlighted by the red arrow on the picture below.

So far, we have learned that a lichen is a symbiotic form between a fungus and an alga…

A nice discovery! But it is not that simple.

The world of fungi is complex, and its forms are variable and sometimes incongruous. Look at the lichens on the tree with a magnifying glass or get closer to the lichen to see them with the naked eye… Another world, isn’t it ?

The multispecies assemblages

Researchers tried to recreate a lichen in a lab by assembling the different organisms – algae and fungi. But…. a lichen did not emerge from this combination. Further research has shown that the lichen is probably composed of a third organism, a single-celled yeast of the Basidiomycetes phylum (see Box 1).

Two fungi ? Yes… For years, lichens were thought to be an association between an Ascomycete fungus (see box 1) and an alga. This idea had already created controversy at the time in the well-founded taxonomic science. The cooperation between several organisms caused us to question ideas in evolutionary theories. Indeed, evolutionary theories are based on the natural selection of organisms that were most well-adapted to their environment. So, the idea that a species physically seen as 1 individual was, in fact, composed of many organisms was just unthinkable. We’ll talk more about these issues and discoveries later in the walk (here).

The recent discovery of the presence of two fungi was initiated by Toby Spribille (2016) when he and his colleagues studied a yellow lichen (Bryoria tortuosa) that produces a poison called vulpinic acid (which helps to keep snails – including other gastropods – away) and a brown lichen (Bryoria fremontii) that does not produce these toxic substances. These two species had always been considered different… Yet, they are formed from the same species of algae and fungus.

Then what makes them so different ? By analysing the genes of the lichens, Toby Spribille discovered the presence of genes from Basidiomycetes fungi and when these were removed, everything related to the presence of vulpinic acid disappeared. Spribille continued to do more research analysing different types of lichens and found that this Basidiomycete fungus was present everywhere ! Since then, the definition of a lichen has changed.

For more information on Spribille’s research on lichen symbiosis, here is a link to an article.

Lichens contain many mysteries that we are just beginning to discover thanks to the current genetic technologies. For example, we know that the bacteria that form the thallus certainly have an important function in the functioning of the lichen but we do not know how….

Activity

In front of this tree, what do you see ?

A trunk with some lichens. Different shapes. Various colours.

The trunk is the substrate on which the lichen grows. The lichen does not have a negative effect on the tree as lichens do not have roots. They have rhizines which are small attachments made up of fungal cells that allow the lichen to attach to the substrate. Rhizines are one of the ways to identify different species of lichens, as they can have different shapes – e.g. they can be single or double.

The forms of lichens

The thallus can have very different shapes. This characteristic is the first important step to differentiate and identify the species. Here are some of the forms:

– Crustose lichens: these are lichens that form a crust on the substrate and that can hardly be detached from this surface because the rhizines are so deeply embedded. This type is the most common, but also the most difficult to identify because of their various shapes. To take the lichen with you, you would have to take a piece of the substrate: the rhizines of the crustose lichens can go into the substrate, both trunk and stone. The photo below is of a lichen often observed in polluted environments. The name of the lichen is Lecanora chlarotera.

– Leprose lichens: these are lichens that have their crust (similar to crustose lichens) entirely formed of small mealy granules. These leprose lichens form a kind of leprosy on their substrate and are characteristic of a habitat sheltered from rain.

– Foliose lichens: these are leaf-shaped lichens. These lichens can be detached from their substrate relatively easily. You can run a fingernail under the lobe to check. The lobe is the outer part of the lichen thallus, shaped like a leaf. The upper cortex of foliose lichens has a different colour than the lower cortex. This difference in colour is due to a different distribution of algae as the lower cortex has no algal layer.

– Fruticose lichens: these are shrubby (shrub-like) lichens. These lichens are attached by one point on the substrate (called the holdfast) and have radial symmetry, from all their sides the lichen looks the same. Because of the homogeneous distribution of the algal layers, the lower and upper cortexes have the same colour.

There are still many different lichen forms, but for now you have enough information to differentiate a few types.

Activity 2

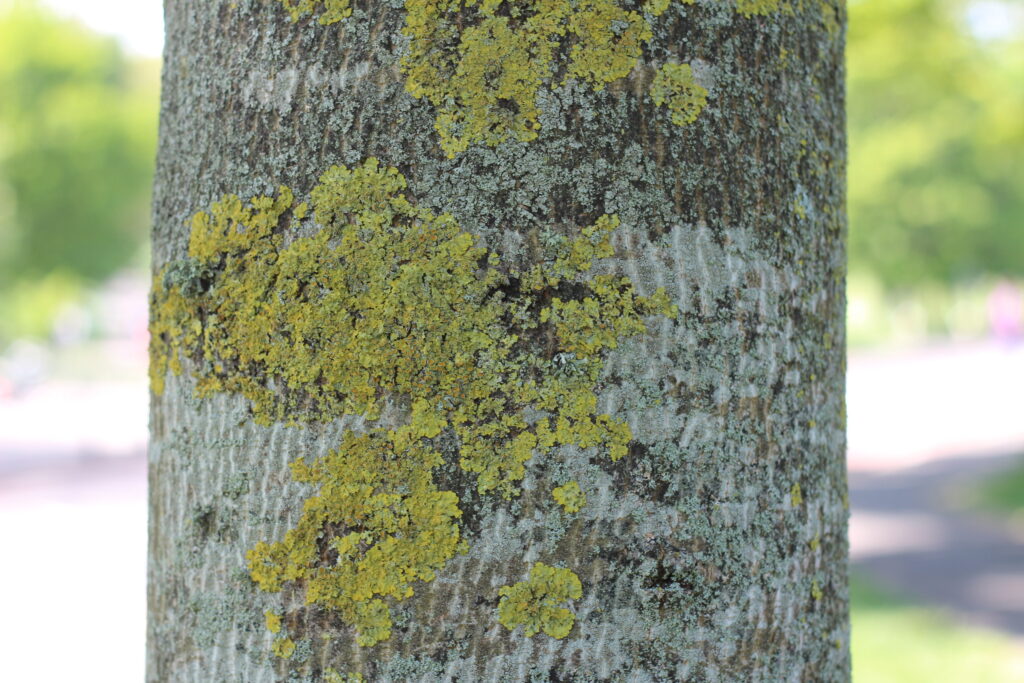

Can you differentiate between the different forms of lichens on this tree ?

Are there different coloured lichens ?

To look at lichens, you need a magnifying glass. If you don’t have a magnifying glass, you can admire the lichens with the pictures below. If you have a magnifying glass but don’t know how to use it, I recommend this video from the British Lichen Society.

Can you spot some lichens that we briefly mention at the last halt ?

We will introduce a common lichen species. The name of the lichen is Xanthoria parietina. The lichens of this genus (it is like the family, Xanthoria) are yellow as you can see on the specimen on the tree. Sometimes these lichens are blue and have yellow edges. Their characteristic is their yellow or blue colour. Their reproductive systems, which are like small yellow mushrooms (see photo) are also another important feature to identify lichens. We will learn more about these structures, called apothecia, later in the walk. They are structures that allow sexual reproduction and contain spores in sacs called asci – structures that define one of the types of fungi that form the lichen, the Ascomycetes.

On the way to our third halt, think about the question below :

Why do you care about lichens ? Why should we care about lichens ?

Feedback

If you don’t continue the ride, can you give us feedback on your experience here ? It will help us improve!

We’ll meet on Leamington Walk next to the Brunstfield Links at the exact location shown below 👇🏾👇🏾