Post by Jacob Copeman and Koonal Duggal

In 2015 the feature film called MSG: The Messenger of God was released in India (Figure 1). It starred the now-imprisoned Dera Sacha Sauda (DSS) guru Gurmeet Ram Rahim playing himself. It was also written and co-directed by him. Marking the guru’s entry into feature films, three further films were released prior to his imprisonment in 2017.

Figure 1. The MSG: The Messenger of God film poster

This development, taken together with his fashion shoots and pop music videos (Figure 2), tells a story of the translation of the guru’s charismatic and performative appeal from printed to moving image, from small to big screen, from saint/baba/guru to ‘Love Charger Baba’, ‘Rockstar Saint’ and ‘Dr MSG’ (Figure 3). It is well known that certain film stars, particularly in south India, are worshipped – often in the cinema hall itself. Here we find the reversal of this – i.e. one who is already worshipped turning film star. Indeed, his transformation from ‘Saint’ into ‘Star’, whose daredevil stunts drew comparisons with major south Indian film star Rajnikanth, inverts standard narratives about fan bhakti (devotion) in which film stars typically become semi-mythological figures and fans turn bhakt (devotee). Moreover, MSG embodied a shift from depiction of gurus in film to the guru as film star playing himself. Why did the guru who already performed live congregational events across various televisual and digital platforms also require the cinematic medium? The answer lies at least in part in cinema’s mass appeal and the DSS’s aspirations to expand its base. The extraordinary reach and significance of cinema in India has been much noted: it establishes a mass public independent of literacy. For the DSS, part of the promise of the enterprise lay in the attempt to harness this reach in order to nurture a mass public of devotees beyond its established constituencies in the north — in addition to the expected Hindi and English it was also released in Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam. As the movement – always subject to a temporality of rush – sought to accelerate a shift from a provincial to a national identity, it is not difficult to see how cinema’s technology of dubbing – self-mythologization in different regional languages – allowed it to retain its expansionist hopes in challenging linguistic circumstances.

Figure 2. Dera Sacha Sauda guru as ‘Rockstar Saint’ and fashion icon on the cover of photo magazine named Spiritual Fusion

The films raise many issues. Restricting ourselves to the first instalment, our focus in this blog is on the guru’s performance in the film of an abundance of special effect-produced miracles, for instance bringing bullets to a halt like in The Matrix, which he then turns into a tiara that crowns his head (Figure 4). He also turns swords into flowers (Figure 5), he flies like superman, though sometimes on the back of a lion; and, uncannily reminiscent of the Modi mask wearing phenomenon, he turns his attackers into visual likenesses of himself (Figure 6).

Figure 3. Still from Love Charger music video

What interests us about the DSS guru’s performance of special effect miracles is how an ostensibly social reformist guru who previously debunked the signature miracles of other spiritual personalities, and to have called – at least rhetorically, and perhaps as an alibi – for his devotees to ‘Please think!’ about such feats, has latterly sought to project his own miraculous capabilities with such fervor. We earlier developed a conception of the DSS’s ‘new order of the miraculous’: a ‘secular-compatible’ order of miracles in which, instead of infringing the laws governing the universe, miracles consist of feats of remarkable speed and quantity — most blood collected in a single day, most bodies pledged for donation, fastest ever construction of a cricket stadium etc. The temporality of rush, time compression and as if spontaneity (but in fact meticulously planned nature) of these feats is ‘inspired by the guru’.

Consider the case of ‘A miraculously huge “Ajooba” [miraculous or wonderful] washing machine,’ described in a DSS publication under the heading “What a wonder it is!”: ‘The washermen [in a Sacha Sauda students hostel] urged [DSS guru] Hazoor Maharaj Ji, and He gave instructions about this wonderful washing machine [which] has the capacity of simultaneously washing 1,000 clothes within half an hour only’. The repeated use of variants of the English word ‘wonder’ is apt in that it is wonderment inside the bounds of natural law that is the hoped-for foundation of such miracles. They are not miracles, but equally they are not-not miracles; apparently compatible with the movement’s professed social reformism – indeed, feats such as most hand sanitizations, most blood donations etc. are precisely enacted in order to combat ‘social evils’ and ‘contribute to society’ – they also evoke a narrative and atmosphere of the miraculous. As one doctor told us of the extraordinary blood donation exploits of the DSS: ‘Baba Ji created a miracle. He made 16,000 people donate blood in one day—it’s definitely a miracle. Nowhere in the world could anyone make 16,000 people give blood in one day. Jesus and other spiritual masters did miracles in their own times based on the needs of society at the time. Jesus had hungry devotees—all of them needed to be fed, and the food multiplied. Similarly, [DSS guru] Hazoor Maharaj created a miracle based on the needs of society’. The doctor’s argument reflects the guru’s emphasis on social utility: unlike the ‘useless’ materializations of ash or rings (characteristic of gurus such as Sathya Sai Baba) that he criticizes so acerbically, the DSS guru’s miracles are miracles that ‘contribute to society’. The labour of such miracles is performed, of course, by devotees. The guru inspires the labour. That is to say, DSS followers are responsible for the miracles they attribute to him. The participatory production of such miracles is ideologically denied by both the movement’s literature and by devotees themselves. The guru’s followers fetishize the energy they have produced together as a power inherent to the guru.

Large-scale follower participation for the achievement of world records is obviously critical. A DSS website advertises world records such as most ever birthday greeting videos (2017); largest ever vegetable mosaic (2014); largest human droplet (2013); and most people tossing coins (2011). In 2012 alone the DSS reportedly created six world records. Under the guru’s guidance, we learn, ‘more than 115 humanitarian works are being conducted and also 55 world records are registered on his name’. In light of this, ‘world record university London has decided to grant Him [a doctorate] degree’. Therefore, ‘from [25th January 2016] onwards Revered Saint Ji will be addressed as Saint Dr Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh Ji Insan’, says the guru’s fittingly named personal website: https://www.saintdrmsginsan.me/.

Figure 4. Dera Sacha Sauda guru turns bullets into a tiara. Stills from MSG: The Messenger of God

What is striking is that it is the guru who is credited for the world record miracles his devotees perform. Partaking of the miracle-records for which they praise their guru, devotees are awestruck by their own ability to be mobilized. Numbers are key: DSS numbers no longer simply represent devotional-humanitarian achievements but are now constitutive of the order itself; the DSS and its guru, a kind of composite of cumulated numbers. Numbers both carry and hide human endeavors. The work, the human devotional labour that generates these numbers becomes invisible as unrecorded background story: they are the guru’s numbers. Numbers make more seamless the conflation of a project whose stated purpose is to provide resources for the stricken and needy with a project of aggrandising and extending the influence and gain of a single person.

But this is not some simplistic story of one-sided appropriation of devotional labour. These are miracles which, in a way, are perfectly in tune with bhakti-devotion: they are participatory. The bhakt is a participant in – co-generator of – miracles. The plaudits received by the guru – the world records writ large in the Guinness Book; the doctorates, acceleration and magnification of personality – they receive, too. They both produce and consume the effects of wonder generated by the DSS. (Compare with the Ford Motor Company’s production in the 1910s of the Model T, the world’s first affordable automobile. A production landmark – with assembly line production instead of individual hand crafting – it was also ground-breaking from a consumer perspective, with workers now paid a wage proportionate to the cost of the car, so providing a ready-made market). Thus, DSS miracles – not miracles, not-not miracles – embody a certain plausible deniability that allows the guru to bridge the anti-miracle social reformism of the movement’s heritage and his own projection of miraculous capabilities (in which devotees participate). The full-palette guru occupies every subject position; here, both social reformer and miracle man: the schismatic guru.

At least, this was the state of miraculous affairs prior to the release of MSG in 2015, which saw the guru’s entry into the domain of special effect miracles – a move that brought his miracles under the purview of the censor board. His adoption of them seemed to signal a step-change: where previously atmospheres of the miraculous were achieved through exaggeration, exorbitance, and mass appropriation of devotional labor, they now were generated through digital manipulation. We would question this understanding however. Certainly, their digital production was novel (for him at least), facilitating all sorts of previously unimaginable incarnations and extraordinary feats. Yet there remained key similarities with the prior order of miracles: in their digital production at least, if not in terms of the feats they depict, they do not infringe the laws governing the universe: they are simply special effects. If previously the miracle was reduced to time compression coupled with bigness, it was now reduced to the digital knowhow of the production team. Indeed, the lengthy disclaimer at the film’s opening plays into DSS hands, allowing it to retain the same plausible deniability characteristic of the DSS’s prior order of the miraculous (‘Of course they are not miracles!’), while continuing to cultivate miraculous atmospheres. Similarly, the new miracles tend to be in the service of ‘good causes’ — combatting the drug mafia etc. — and so retain some legitimizing suggestion of social commitment, even as they augment the guru’s hyperbolic personality.

Figure 5. Dera Sacha Sauda guru turns swords into flower petals. Stills from MSG: The Messenger of God

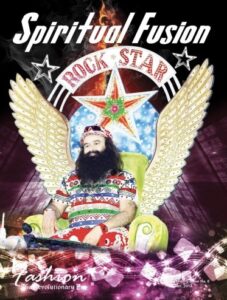

The previous mode of miraculous production, as we have seen, excised devotees even as they themselves generated the exorbitant feats that produced in them effects of wonder. But does not the digital mode of production disavow devotee labour even more fully than in the prior order? In fact the simultaneous erasure of devotees even as their participation is crucial to delivering the film is again not dissimilar to that which came before. Not just devotees but everyone involved in creating the film is subordinated to the totalizing figure of the guru. Publicity seemed to deny almost any participatory sense of its production, instead again fetishizing the energies and capacities of the many as a singular property of the magnetizer-guru. MSG reportedly was written and produced by the DSS guru. But not only that. ‘He is also its co-director, co-costumer designer, co-choreographer, co-editor, co-action director, stuntman, lyricist, singer, music director and of course, the lead actor’; and yet devotees, necessarily, are ever present, too (Figure 7). They are the indispensable constituency that the superhero ‘saves’, they form the exorbitant crowds in the many crowd scenes, they are the necessary primary witnesses of his special effect miracles; indeed, MSG holds the world record for most ever – in excess of a million – film extras, a further ‘proof of wonder’. They were necessary, too, if one is to believe the reports, in order for MSG to attain the feat of highest grossing opening week in Indian cinematic history – yet another record and proof of wonder. So the simultaneous erasure of devotees and critical participation of and dependency on them is in fact maintained in this modified digital order of the miraculous.

Figure 6. Enactment of Modi mask wearing phenomenon as Dera Sacha Sauda guru turns his attackers into visual likenesses of himself. Still from MSG: The Messenger of God

How were devotee understandings affected when his miracles began to be conveyed cinematically? Devotees’ online comments, and our own interactions with devotees, suggest that while they remain fully aware that the miracles depicted are not real, the film nonetheless augments the atmosphere of miracles and wonder. The guru, as we have noted, has railed in his discourses against showy miracles: ‘Saints [such as he] hold satsangs in which they don’t put on any spectacle (tamasha) where they touch a thing and it becomes a ring (anguthi), where rice will come, or ashes (rakh) materialize. This is the work of a magician, not of a saint. “I’ll make you live. I’ll kill you.” The saints can do it, but they don’t do it’. Devotees see in MSG what the guru can or could do but holds back from doing in ‘real life’ contexts of devotion, even as a process of ‘image transference, from screen-to-street’ takes place, such that the digital miracle comes to augment the atmosphere of miracles in ‘extra-cinematic space’. Above and beyond even the flamboyance of his singing and modelling, it is MSG that is the guru’s id – no holds barred miraculous spectacularism. More pertinent still is the sense that obviously machine-made miracles are incapable of lying. MSG is a presentation of what the guru otherwise holds back or keeps hidden; a demonstration of all that he keeps in reserve.

Figure 7. Self-proclamation as The Most Versatile Person in the History of World Cinema. Still from MSG- Lion Heart official trailer

A final point concerning the devotee-crowd and the power of the guru. The devotee-crowd – whose mass body is put to performative work in the form of collective blood donor, hygienic exemplar or film extra – is controlled by the guru ‘for now’ but potentially uncontrollable; facts that the film vividly discloses. This is particularly pertinent in respect of the criminal charges that the guru faced at the time; for his arrest and conviction in 2017 were indeed followed by multiple casualties as devotees directed their violent anger against authorities. As Piyush Roy wrote shortly afterwards, the film features the guru ‘playing a larger-than-life version of himself, as the satguru, saviour and “father” of a million plus people on-screen, and another 5 crore [50 million] hinted to be constantly lurking in the background. In an ominous forecast of the post-conviction mayhem in Panchkula, his followers in the film frequently hint at thwarting any challenge coming their pitaji’s way, though violence, if necessary’. The film thus also served as a demonstration of power – evidence, once more, of all that the guru keeps in reserve, of unexploited potentiality (at least, in the sense of an armed force; devotees’ potentiality is harnessed in other ways of course). A peculiarity of the film is the literal place of its audience within it; the susceptibilities of the censor board’s non-deliberative public, at once ‘passive and hyperactive: easily duped by any passing demagogue and constantly on the brink of violence’, are on display in the film itself. Police entering the dera after the guru’s imprisonment found an arsenal of weapons. If the devotee-crowd of the film largely took the form of a spectator spectating itself – benignly wondering at its own generation of wonder effects (arrogated to the figure of the guru), its potentiality remaining mediated (contained) by him – we are also shown that were he to be taken from it the result would likely be this potentiality’s devastating uncontainment. Apart from anything else, then, the devotee-crowd formed a demonstration of power and warning to state authorities: stay back from the fiefdom.

Jacob Copeman is Research Professor, University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain, and Distinguished Researcher (Oportunius), Galician Innovation Agency (GAIN).

Koonal Duggal, Research Fellow in Social Anthropology at the University of Edinburgh.

Still from MSG: The Messenger (2015)

Still from MSG: The Messenger (2015) But, once in, you are treated to such a never-before-seen roller-coaster of wooden acting, whiny diction and cringing parade of crazy costumes that it’s tad difficult to look away. Mounted on a massive scale of real human extras that great epics from Hollywood would be envious of, MSG with its curious hook of ‘what next and how much bigger…’ had the B-Movie fan in you glued to the end. It’s one of those unintended movies that attract cult viewing ‘for being too bad to miss’!

But, once in, you are treated to such a never-before-seen roller-coaster of wooden acting, whiny diction and cringing parade of crazy costumes that it’s tad difficult to look away. Mounted on a massive scale of real human extras that great epics from Hollywood would be envious of, MSG with its curious hook of ‘what next and how much bigger…’ had the B-Movie fan in you glued to the end. It’s one of those unintended movies that attract cult viewing ‘for being too bad to miss’!  MSG is a unique aspiration exercise in India’s most prolific desi super-hero franchise (five films in two years – MSG 1 & 2, MSG: The Warrior Lion Heart 1 & 2, and Jattu Engineer), written and produced by Ram Rahim. He also is its co-director, co-costume designer, co-choreographer, co-art director, co-cinematographer, co-editor, co-action director, stuntman, lyricist, singer, music director and of course, the lead actor. Ram Rahim thus broke Bollywood’s long-standing record of a multi-tasking Manoj Kumar, who used to write-direct-edit-produce-and-act in most of his later home productions.

MSG is a unique aspiration exercise in India’s most prolific desi super-hero franchise (five films in two years – MSG 1 & 2, MSG: The Warrior Lion Heart 1 & 2, and Jattu Engineer), written and produced by Ram Rahim. He also is its co-director, co-costume designer, co-choreographer, co-art director, co-cinematographer, co-editor, co-action director, stuntman, lyricist, singer, music director and of course, the lead actor. Ram Rahim thus broke Bollywood’s long-standing record of a multi-tasking Manoj Kumar, who used to write-direct-edit-produce-and-act in most of his later home productions. Breaking records, incidentally, seem to be a fascination for Ram Rahim, with each of MSG’s song and dance extravaganzas unfolding on an auditorium size-stage with a million plus extras. The Google credits Ram Rahim and his Dera with multiple world records from planting most trees in a single session to organising camps with record blood donors, most blood pressure readings and diabetes screenings (in a day), the largest display of oil lamps (1,50,009 lamps), the largest finger painting (3,900 m²), the largest vegetable mosaic (1,858.07 m²) to even the most number of people sanitising their hands simultaneously (7,675).

Breaking records, incidentally, seem to be a fascination for Ram Rahim, with each of MSG’s song and dance extravaganzas unfolding on an auditorium size-stage with a million plus extras. The Google credits Ram Rahim and his Dera with multiple world records from planting most trees in a single session to organising camps with record blood donors, most blood pressure readings and diabetes screenings (in a day), the largest display of oil lamps (1,50,009 lamps), the largest finger painting (3,900 m²), the largest vegetable mosaic (1,858.07 m²) to even the most number of people sanitising their hands simultaneously (7,675). At heart, MSG is meant to be a patriotic film with a reformist heart that celebrates a range of Indian political ideologies from Gandhi’s message of winning one’s opponent through non-violence to PM Narendra Modi’s ‘Clean India’ campaign. Ram Rahim’s on-screen entry is preceded by a collage of leaders from India’s Independence movement like Gandhi, Sarojini Naidu, Madan Mohan Malviya, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, even Lord Mountbatten, (though there is no sighting of Jinnah).

At heart, MSG is meant to be a patriotic film with a reformist heart that celebrates a range of Indian political ideologies from Gandhi’s message of winning one’s opponent through non-violence to PM Narendra Modi’s ‘Clean India’ campaign. Ram Rahim’s on-screen entry is preceded by a collage of leaders from India’s Independence movement like Gandhi, Sarojini Naidu, Madan Mohan Malviya, Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel, even Lord Mountbatten, (though there is no sighting of Jinnah). Ram Rahim addresses himself as a fakir, but is seen in elaborate never-repeating costumes that feature some heady imaginations with bling that you would ever see. He rides fancy vehicles, from cycle and tractors to a lion with wings, i.e. when he is not himself flying with his hands as wings and legs as parachute. He endorses multiple religious icons – Ram, Allah, Waheguru; and insists on fighting against every social evil – corruption, drug abuse, prostitution, etc. – albeit, as a single-handed miracle worker.

Ram Rahim addresses himself as a fakir, but is seen in elaborate never-repeating costumes that feature some heady imaginations with bling that you would ever see. He rides fancy vehicles, from cycle and tractors to a lion with wings, i.e. when he is not himself flying with his hands as wings and legs as parachute. He endorses multiple religious icons – Ram, Allah, Waheguru; and insists on fighting against every social evil – corruption, drug abuse, prostitution, etc. – albeit, as a single-handed miracle worker. Interestingly, he takes the idea of being comfortable with one’s self, to an altogether different level of dare in our chiselled times, by not batting an eyelid before baring his hairy-bear self or his love handles through outfits un-flattering hugging his corpulence.

Interestingly, he takes the idea of being comfortable with one’s self, to an altogether different level of dare in our chiselled times, by not batting an eyelid before baring his hairy-bear self or his love handles through outfits un-flattering hugging his corpulence. No one discounts that MSG and the subsequent Ram Rahim helmed films had an agenda. None can now deny that a lot was hunky-dory under his publicised ‘reign of bliss’ at the Dera. But anyone with an iota of filmmaking experience can also not deny that to assemble such a humongous cast of real people as happy extras and then getting the best out of them isn’t the outcome of faith and fear alone. What made so many see a spiritual guide in someone with such an unabashed lust for material possessions in a culture that used to associate simplicity and renunciation with saintliness, warrants introspection. If religion, as Marx said could be ‘the opium of the masses’, Ram Rahim for sure served a recipe of relief, even if momentary, for at least some in our compromised times of compromising idols.

No one discounts that MSG and the subsequent Ram Rahim helmed films had an agenda. None can now deny that a lot was hunky-dory under his publicised ‘reign of bliss’ at the Dera. But anyone with an iota of filmmaking experience can also not deny that to assemble such a humongous cast of real people as happy extras and then getting the best out of them isn’t the outcome of faith and fear alone. What made so many see a spiritual guide in someone with such an unabashed lust for material possessions in a culture that used to associate simplicity and renunciation with saintliness, warrants introspection. If religion, as Marx said could be ‘the opium of the masses’, Ram Rahim for sure served a recipe of relief, even if momentary, for at least some in our compromised times of compromising idols. The memory of his crime’s long distance from punishment may have made the Baba of Bling gravitate with a new-found lure towards the tinsel world like a rejuvenating attraction of a parallel career happening mid-life. With an assured fan base of politicians across ideologies, just when Ram Rahim was all set to become Bollywood’s latest B-Movie star in superhero spectacles with a Marvel-comic like proliferation, the Master-Writer up there, introduced a blast from the past twist to script a dramatic anti-climax far memorable than any of His imposter namesake’s films.

The memory of his crime’s long distance from punishment may have made the Baba of Bling gravitate with a new-found lure towards the tinsel world like a rejuvenating attraction of a parallel career happening mid-life. With an assured fan base of politicians across ideologies, just when Ram Rahim was all set to become Bollywood’s latest B-Movie star in superhero spectacles with a Marvel-comic like proliferation, the Master-Writer up there, introduced a blast from the past twist to script a dramatic anti-climax far memorable than any of His imposter namesake’s films. The article was first published as a column piece in Sunday Talkies column of Orissa Post, Sept. 3 2017.

The article was first published as a column piece in Sunday Talkies column of Orissa Post, Sept. 3 2017.