Post written by Abi L. Glen

What follows is a dash through some Serious Research I’ve been thinking about for a while: the historical use of pigs in alcohol advertising. I spend a lot of my academic life questioning how animals are represented in various places; I’ve written pretty extensively on the negative uses of pig images (antisemitism, misogyny, etc) and ‘pig’ as a linguistically loaded term. Now, something a bit lighter.

My favourite pub in Cambridge is called The Flying Pig. It’s a delicious eyesore near the station, which used to be a desert a million miles from town (the University, of course, scorning a station as a site of ill-repute). ‘Investment’ has meant a score of luxury condos, Wasabis, and Sainsburys Locals, for those who commute to London but like to pose on a punt at the weekends. In amongst this slightly brittle and soulless new town, the Pig is digging its trotters in. It’s one of Cambridge’s last Free Houses, and the unofficial watering hole of the long-running Folk Festival: the walls are plastered with posters of festivals past. They don’t do food, unless you count a truly magnificent selection of dodgy corner-shop crisps. Pink Floyd used to drink there. It’s possible to get 15% beer. It’s proper, and slightly ornery, and I love it, not least because of the name.

That name. There’s an issue of the Spectator from 1710 where someone sounds off about the rise in daft pub names (listing ‘The Flying Pig’ as one of them). But names and signage were an important historical issue; in the same way that license-holders now need to be clearly identified, medieval law insisted that tavern owners marked their properties as places to sell alcohol. Take this example of a local writ in 1430: ‘Whoever shall brew ale in the town of Cambridge with intention of selling it, must hang out a sign, otherwise he shall forfeit his ale’. Pictorial inn-signs are also a relic from an era of high illiteracy.[1]

While the most common animal sources for pub names are ‘lion’, ‘swan’, and ‘stag’ (heraldic influence, of course), we do see a few pig-pubs. The most common is The Pig and Whistle. I’ve investigated this (I had initially assumed it was a bit of whimsy) and apparently it’s a bastardisation of ‘Byggen Wassail’, a medieval feast celebrating the end of the barley harvest. Its common use in the North East of the UK in all likelihood reflects the Danish and Viking heritage of the locals.

Pig and Whistle sign: Brian Curtis (pub is in Dover, Kent).

That leads us to the clearest connection we have between pigs and the alcohol industry: medieval husbandry. Even amongst the peasantry, most households had a pig, generally tended to by the lady of the house. Home-brewing was also common across Europe. Thus developed the custom of feeding brewery dregs and beer mash to the hogs (one Andrea and Cath are cheekily subverting in their toys). But what about the alcohol content? Drunken animals (especially birds who peck at fermented fruit) are all over the internet. It makes sense that pigs with a taste for mash would enjoy a cold liquid version; they need all the help they can get to control their body temperatures, after all. Here’s a picture of one of my favourite writers (Sy Montgomery)’s pet, Christopher Hogwood, sucking down a cold one:

Hogwood: Sy Montgomery for the Boston Globe

Normally, medieval swine could nibble on grass, tubers and roots. In the run up to slaughtering season (Christmas), this diet was supplemented by a ton of acorns. High in calories and fat, but easily sourced, this was the preferred method of getting the best from your investment. The practice was so commonplace that most medieval almanacs and calendars depict November with an image of swineherds, thumping acorns down from the trees for their hogs to gobble. This was itself a booming business for landowners of wood pasture; pannage fees [to allow you to fatten your pigs] were widespread: surveyor scribes often recorded the size of a woodland based on how many pigs could graze there (silva n porci).

Acorns and Hogs from Psalter: British Library, Royal 2 B VII, f. 81v.

Image in the public domain; digital image courtesy of British Library,

London, UK

Fallen apples were also ripe (sorry) for snaffling in the orchards and open forests where hogs grazed year-round. I reckon this accounts for the links between pigs and cider: a pastoral dream of mushed apples and leisure. Farmers these days are bringing pigs back into the orchards, as a more eco-friendly form of pest control: a farm in Michigan is using a bunch of Gloucester Old Spots to nibble beetle larvae and hoover up infected apples (it won’t harm them; amazingly, pigs store venom and toxins as fat—which is why they can eat poisonous snakes and their own poop, no bother). Incidentally, here’s an adorable fact I learned recently: folklore suggests that the spots are bruises from fallen apples. Cute.

Gloucester Old Spot: Robert Dowling for The Guardian

Rattling on through to the 18th century, we see some interesting linguistic changes. Around 1750 is the first recorded use, in deepest Herefordshire, of ‘a pint of squeal’ or ‘squealpig’ to refer to a glass of cider. Apparently this is a tradition that persists, as is the custom of referring to an ale jug as a pig.

All of this has laid the foundations for the use of pigs in modern alcohol advertising. I’ll cover more ground on this in the future (and believe me, it’s pastures-worth) but here are 3 short case studies from across the world.

North America: WhistlePig

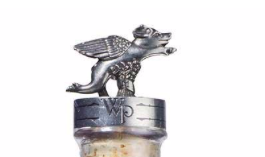

An upstart rye company, based in Vermont (and a nice riff on ‘pig and whistle’; I wonder if this has speakeasy significance?). Most interesting for my purposes here are their Spokespig, Mortimer Jr (shown in his full glory, below) and their bottle design: more accurately, for the fantastically named Boss Hog range. Each year they release a new edition of their premier offering, featuring a pewter bottle stopper. These stoppers are themed and charming: 2017’s offering— Armagnac aged— features a chain-mailed hog in reference to Prince Edward, The Black Prince, who famously looted the finest Armagnac barrels from France. I love that this also harks back to the tavern signs and their allegiance to the monarchy.

Mortimer the Hog: Alberto Baccari for WhistlePig Whiskey Ltd

Pewter bottle stoppers: WhistlePig Whiskey Ltd/ Master of Malt

Spain: Gran Cerdo

Gran Cerdo: Tivoli Wines

I first tried this in a bottle shop in SE London

and became quite hysterical with the name’s origin. ‘Gran Cerdo’ [literally: Big Pig] is a term of sass, akin in Spanish to a more vituperative ‘fatcat’. When the bank rescinded its loan as the wine wasn’t a taxable asset, the makers crowdfunded and bottled it anyway. The label features a hog’s mouth stuffed with dollar bills, and a feisty:

You corpulent, sweaty suit-wearing people, someday you’ll discover that some of the most important things in life aren’t assets you can impound. Thanks to our friends, with their help we finally got this wine bottled. Now you can enjoy our baby, try it with pasta or ham.

England: Orchard Pig

Founded in a shed in Somerset, OP play off every bucolic stereotype: the proximity to Glastonbury, the muted colours, the fact that the company is named after the ‘original orchard pigs’ who shared the founder’s smallholding.

OP isn’t the only English cider to have ‘pig’ in the title, but my god it’s the most extra. The snazzy silhouette logo. The puns (I love the ‘Sty News’ section). But mostly: THE GLAMPIG.

GlamPig: Orchard Pig

This is the height of holidaying, the Valhalla of vacationing. A glamping pod with its own festoon lighting, snazzy hot pink deck chairs, and a built-in bar. Originally a PR stunt for their new Pink Pig cider, this brings together all of the historical influences I’ve discussed above (pastoral cabin, based in an orchard, etc), updated in millennial pink for the ‘gram.

With that: I’m off on my own trip (not in a Trojan Hog, sadly). When I’m back, I’ll be publishing my interview with Prof. Francoise Wemelsfelder: expect lots of chat on Quantitive Behavioural Analysis, being an emotionally attuned scientist, and me doing some fairly embarrassing fangirling.

[1] Signs were also key in a competitive market; see Cat Dent’s paper for more on this:

https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/cross_fac/iatl/reinvention/archive/volume4issue1/dent/#notes