Liz Stanley

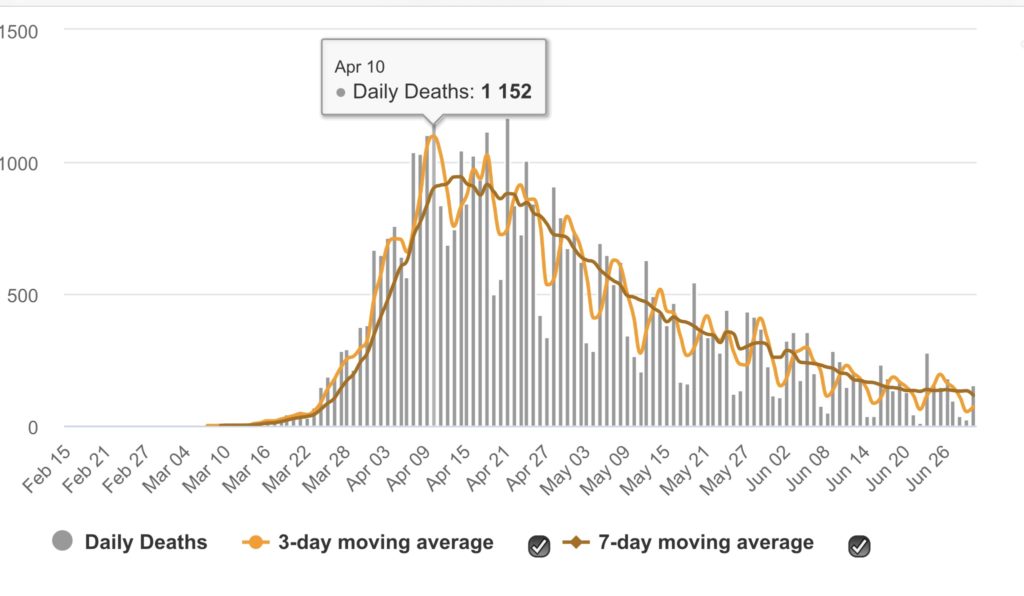

For people following the daily toll of infections and deaths from the coronavirus, the www.worldodometers.info website provides a useful source in providing a day-on-day collection of a wide range of composing statistics for countries around the world. At the time of writing, the most recent death figures for the UK are shown in the Figure here.

‘The numbers’ remain of key concern, and perhaps as a result they are often taken at face value with their origins, data source and validity bracketed away. Alongside this, although perhaps not quite as prevalent as they were even a month or so ago, new representations are still appearing of ‘what the virus looks like’, with every week another depiction to add to the archive. However, the status of ‘the image’ and whether these are ‘real’ or artistic productions or some amalgam remains usually hard to discover (as commented in an earlier blog-post ‘What does Covid-19 look like?), for only rarely does copyright information appear, let alone more detail given.

Together with ‘the numbers’ and ‘the image’, ‘the expert’ is a familiar presence in public speaking or writing about the pandemic and its effects, along with ‘the science’. ‘The numbers’ as above appear almost in a vacuum, ‘the image’ is usually a free-floating one that just ‘is’, and in what sense ‘the experts’ have expertise other than through what they are saying or writing is often not referenced beyond a job title seen to accomplish this job of work. Linking the numbers, the image and the experts is correspondingly quite hard to do. And concerning all of them, what Harold Garfinkel referred to as the ‘forgotten whatness’ of the work involved is bracketed and made invisible. What is stressed as important is the product and readers/users consuming the product, rather than awareness of the process engaged in and the links between one sphere of coronavirus knowledge and others. This makes it difficult for readers to get a purchase on and assess the status of claims being made.

Sometimes expertise can inhere in specific individuals. For instance, in early March 2020 it was possible for The Guardian newspaper to name Christian Dronten as the leading coronavirus expert in Germany, something likely to be impossible now.

Fauci in the US and Whitty in the UK, key officials in the health sphere, do not have this status, and most likely nor now does Dronten in Germany, for expertise has proliferated and much work has underpinned this. To an important extent this has been due to the mass media and the way that journalism works contemporaneously. TV, radio, press, media websites and other mass media require experts for their working practices. These seek people to act as such, as certified expert sources that can be reported on, for even media journalists with specialist titles (such as health correspondents, for instance) rarely carry out investigative journalism but rely on interviewing people seen as appropriate certified sources. There are of course exceptions, but these are fairly rare and what largely exists is the recycling of what ‘the experts‘ say by ‘news’ reporters.

The production of expertise also inheres in people labelling their activities and/or knowledge-base in professional/institutional (and largely academic) fora as that of expertise. This is facilitated by the high need context, and encouraged at institutional level as promoting skills and knowledge that will enhance the reputational standing and perceived capability of institutions as well as particular persons and sub-units. Experts may be self-made and self-reproducing in relation to both the media market and the research market, then. The LSE’s Department of Health Policy, for instance, has an ‘Expert Analysis Coronavirus’ page with quotations from podcasts by named experts. No further information about their spheres of expertise appears, although searching the LSE site generally provides the information that they are involved in a global health policy Masters degree.

UCL along with other universities features a number of experts in the area who appear on designated webpages. By the start of July 2020, a growing number of academic coronavirus expert centres have been popping up and promoting themselves as providing expert commentary and research capability, and more can be expected to follow. The pop-up expert proliferates.

Government too is involved. In the UK in early March 2020, people with “expertise relating to the Covid-19 outbreak or its impacts” were invited to sign up to a government database, which around 5500 did.

Following this, over 1100 completed a survey which asked for responses to short, medium and long-term concerns. Some of the people who appear elsewhere in the media and on university website pages as designated experts appear in this list, provided in a sub-page, while other publicly-appearing experts do not. Tracing the professional locations and areas of expertise of 40 randomly selected list members suggests a range from a very specific professional expertise through to a very broad or even rather tenuous idea of expertise “relating to the Covid-19 outbreak”. Governance requires expertise and either seeks out known people to act as such, and/or invites people to present themselves as such. The authority and legitimacy of governance, as well as government more narrowly, is linked to an appropriate use of expertise, although in practice this may be highly managed and distanced.

Other experts, in survey data and quantitative methods, produced an analysis of the survey responses. The result is as might be expected a rather general account of their concerns, many of which indicate not so much focused expertise as simply general knowledgeability. For example, in relation to infrastructure concerns, “experts are concerned about public transport. They worry about the reduction of services and want clear guidance on how to say stay safe while travelling… “, and “Digital infrastructure is also an area of concern. Experts worry it will struggle to continue to cope with increased demand”. Indeed – but is there anybody halfway awake who does not think this? Some more detail on sub-pages is provided behind these anodyne statements, but not a lot that would take the reader beyond general knowledgeability.

The ‘COVID-19 Expert Reality Check’ website, with its homepage shown here, is an interesting exception to a number of these patterns. It provides information about the origins and status of the virus image shown on the homepage and assigns ownership. It makes clear it is part of Johns Hopkins University’s Public Health Department. Its listed information essays are authored by specified individuals, and clicking on links provides information about who they ‘are’ in an organisational sense, enabling the reader to assess the link between the information and the author’s professional expertise. Sometimes the result is thereby shown to exceed expertise, the ‘Could SARS-CoV-2 be transmitted sexually via semen?’ statement being a case in point. Stating ‘as fact’ that sex is impossible from a six-foot safe distance, the associate professor of surgery author seems not to have heard of telephone or internet sex or that semen and penetration might not be involved. Perhaps one of the points of the above patterns is that they stand between experts and attentive knowledgeable readers who problematise or reject their claimed knowledge.

‘Experts’ has become a buzz term, with web- and academic-database searches concerned with coronavirus throwing up many items where those referred to as experts think or comment this or that.

Some of these people become proficient and proactive in pre-packaging their activities, outputs and knowledge-base in a way that makes for easy use as demonstrably ‘expert’ by mass media and governance. Managing media take-up is an important element in this. But beneath ‘X, says expert Q’ comments lies diverse expertise that ranges from very focused high-level professional competence in specific areas, to informed and in some cases not so informed knowledge of a general kind. And rarely commented on is that many of them disagree with each other, and also over time change their minds quite significantly from their own earlier comments. This reminds us that expertise and knowledge are not static possessions, but are produced through investigation and interpretation made in a particular time/place and shaped for an audience, with the ‘forgotten whatness’ of the work involved being crucial, although absent in most public presentations and representations of ‘expertise-ness’.

What provides experts with expertise is largely bracketed, then, but is partly a product of the working practices of others, partly reputational as they become established as experts by receiving coverage as such, partly inheres in professional position and title, partly is connected with high need knowledge contexts, and partly rests upon specific knowledge and competence. All of these are involved in the ‘whatness’, not just the latter. And the more experts become established as such in a public context, the more the drift is towards becoming talking heads. That is, the public intellectual role that experts take up can expect and lead them to expound on topics outside their sphere of knowledgeability and expertise.

What is an expert? It’s complicated, and the complications need to be recognised and a careful eye cast over them.