In the early 1900s in New York, a strange event took place in the upscale enclaves of Long Island. Many of its denizens began to mysteriously contract typhoid. The emergence of a disease associated with filth and poverty in a slick and affluent quarter deeply unsettled the city’s medical establishment.

A sanitary engineer named George Soper was asked to investigate the phenomenon. He discovered that a cook named Mary Mallon, a middle-aged Irishwoman, had worked for at least eight of the families that had been attacked by typhoid. Mallon, herself perfectly healthy, would leave her employment each time a case broke out and move to another family. Soper set off on a hunt. He traced Mallon’s whereabouts, stalked her to find where she lived, and finally confronted her, accusing her of being a carrier of typhoid. When Mallon refused to cooperate and undergo medical tests, Soper convinced the police to arrest her.

Incarcerated purely on a hypothesis, Mallon’s blood, urine and faecal samples were then collected against her will. When the results came back, they showed the presence of Salmonella typhi, the bacterium that causes typhoid, and the noose of public disapproval quickly fell around her neck.

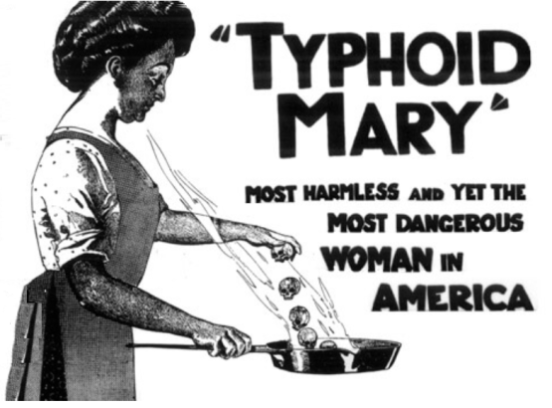

Soper was celebrated for having established the existence of ‘healthy carriers’ — people who carry and spread disease-causing pathogens but stay unaffected. Mallon was disgraced and went down in history as ‘Typhoid Mary’.

For decades, that unkind moniker normalised the violence and vilification of a poor, illiterate, immigrant woman, who was also a passionate and gifted cook. Mallon was demonised by the medical establishment and the press as a ‘super-spreader’, akin to a mass murderer. She was believed to have infected 51 people, three of whom died, but exact numbers were difficult to establish.

Finding the enemy

Mallon was sent into quarantine for 26 years, next to the Riverside Hospital on North Brother Island, where she finally died in 1938. An impassioned exoneration came 63 years later, from an unexpected yet unsurprising quarter. In Typhoid Mary: An Urban Historical (2001), the late Anthony Bourdain wrote with great empathy for his fellow chef: “Cooks work sick. They always have. Most jobs, you don’t work, you don’t get paid. You wake up with a sniffle and a runny nose, a sore throat? You soldier on. You put in your hours. You wrap a towel around your neck, and you do your best to get through. It’s a point of pride, working through pain and illness.”

Typhoid outbreaks were not new to New York City, but Mallon had been singled out as a public enemy, more deadly than the disease itself. Her true crime, perhaps, was reminding the rich and powerful that pathogens had little respect for the class divide that separated Long Island from the Bronx.

***

The story of people and pathogens is that of a difficult evolutionary marriage. Pathogens want to live and prosper. Killing off humans — the hosts — would become a self-defeating exercise. Both parties, therefore, try to work towards mutual survival. After a certain point in time, the two declare an uneasy truce and humans start to live with the pathogen. We have done so many times before, and we will do so with the novel coronavirus.

The biological coexistence that emerges out of a pandemic is in stark contrast to its social effects. Diseases don’t have a social preference, and pathogens don’t distinguish victims by race, class, religion, gender or other identities. However, history shows that each time there is a pandemic, deep-rooted social prejudice resurfaces, often with horrifying results.

During the Great Bubonic Plague in Europe in 1348, the Catholic Church was convinced that the Black Death was a Jewish conspiracy to undermine Christianity. Accused of poisoning wells to spread the disease, Jews were subjected to horrific torture and forced to make false confessions. Soon, the mephitic smell of the burning flesh of thousands of Jews lingered in the air of Strasbourg, Cologne, Basel and Mainz.

The Roma of Europe faced similar persecution. Giorgio Viaggio, in his book Storia Degli Zingari in Italia (1997), has documented 121 laws framed in Italy between 1493 and 1785, restricting the movement of Zingaris (a pejorative term for Romas). Such laws were driven partly by the prejudiced view that the Roma people caused and spread epidemics.

In medieval Europe, outbreaks of plague were blamed on people who practised traditional medicine. They were branded ‘witches’ and persecuted. Historian Brian Levack (2006) estimated that 90,000 people were punished for witchcraft in Europe. Though we don’t have exact figures, the brunt of it seems to have been borne by women.

***

The medieval belief in plague spreaders was dispelled with the arrival of germ theory. Diseases were spread not by people but by micro-organisms or pathogens. They could travel through air, water or physical contact between humans and non-humans. We learnt that germs had no regard for social categorisations. One assumed that the discovery of this apolitical and amoral ‘germ’ would lead to epidemics being seen through the clear lens of a microscope and not by glasses tinted with prejudice.

But the microscope was not only an instrument of discovery; it was a tool of the Empire. The tropics were teeming with diseases, detrimental to the health of Anglo-European administrators. Mosquitoes, it seemed, were far more insurgent than colonial subjects. It was the microscope that shaped the colonial understanding of “tropical disease”. The outbreak of ‘Asiatic cholera’ in 1817 — a pandemic named because it was believed to be endemic to India’s Gangetic region — soon spread to Europe and sparked fears of an invasion of diseases originating in the colonies.

This prompted intense scientific enquiry. In his nuanced account of the attempt of 19th-century medical science to localise diseases, historian Pratik Chakrabarti writes in 2010 of how Robert Koch’s discovery of Vibrio cholerae — the comma-shaped cholera pathogen — was pinned to the tropical environment and body. Specifically, the intestine and biliary tract of the colonial subject.

Then there was leprosy, so stigmatised that the word ‘leper’ became synonymous with a social outcast. The Manusmriti mandated the ostracisation of lepers as ‘sinners’. Even after the Leprosy Commission report in 1891 concluded that the “amount of contagion is so small it may be disregarded,” Indian and European upper classes actively campaigned against allowing the afflicted to be seen in public, as their sight produced disgust and loathing. This led to the Leprosy Act of 1898, which institutionalised people with leprosy, even using gender segregation to prevent reproduction. All to please the aesthetic sensibilities of the colonial elite.

If colonial science contributed to the tropicalisation of epidemics, literature reified it. Thomas Mann’s novella Death in Venice, set in the city of water during a cholera outbreak, described the disease as ‘Indian cholera’, which, “…born in the sultry swamps of the Ganges delta, ascended with the mephitic odor of that unrestrained and unfit wasteland, that wilderness avoided by men…”.

Epidemic orientalism

Researcher Alexandre White in 2018 referred to such incidents of colonial construction as “epidemic orientalism” in his thesis. This often shaped the way diseases were named — Asiatic cholera (1826), Asiatic plague (1846), Asiatic flu (1956), Rift Valley fever (the 1900s), Middle East respiratory syndrome (2012), Hong Kong flu (1968), to cite a few. Now, the World Health Organisation has guidelines to name infectious diseases in neutral, generic terms.

Socially, however, epidemics and diseases continue to be pinned to race, gender, sexual preference and geography. The Trump administration has repeatedly called COVID-19 the ‘Chinese virus’, and some refer to it as ‘Kung Flu’. Naming reinforces prejudice. The original term for HIV/ AIDS was the acronym GRID — Gay Related Immunodeficiency. Though short-lived, it worked to boost what American televangelists were already calling it in the 80s: “gay plague” — divine punishment for sexual deviance. The belief that HIV/ AIDS has a preference for gay men now lives on in legislation in various countries, prohibiting men who have sex with men (MSMs) from donating blood or organs.

***

If history tells us one thing, it is that we have managed to deal with disease-causing pathogens significantly better than with our entrenched prejudices. Pandemics don’t produce hate, but they do serve to amplify it.

The Trump administration would like to believe that the Chinese government’s mismanagement and attempts to cover up the incidence and spread of COVID-19 is a conspiracy aimed at destabilising America. It recalls the Catholic Church’s invocation of the notion of pestis manufacta (diabolically produced disease) to accuse Jews of trying to sabotage Christianity. Similarly, European politicians Le Pen and Salvini’s racist invectives against migrants and refugees as carriers of the coronavirus intersects with Trump’s rhetoric. During his campaign for the U.S. presidency four years ago, Trump revived the medieval European idea of ‘plague spreaders’ by claiming, “Tremendous infectious disease is pouring across the border” carried by Mexican immigrants. Ironically, it is Mexico today that’s guarding its borders from carriers entering from the U.S.

India’s latent prejudices have similarly risen in tandem with COVID-19. Building owners have barred entry of medical staff into their own homes. People speak of social distancing using the terminology of caste and untouchability. People from Northeast India are facing racist comments and threats of eviction. The same government that sent planes to ferry Indians back from foreign countries failed to house its poor migrant labourers or to send them safely home. The ongoing lockdown has seen a mass exodus of workers, trekking hundreds of kilometres to get home, sleeping on streets, struggling for food and water. Some 20 have died so far. As this goes to press, governments are scrambling to set up relief camps for those persuaded to stay back, and transport those who insist on leaving. And in U.P., returning workers are hosed down with surface disinfectants as if they were the pathogens. Added to this, communal prejudice has found new viral spread, riding piggyback on the Tablighi Jamaat conclave in New Delhi’s Nizamuddin area.

***

Science was supposed to liberate people from irrational beliefs by proving that pathogens don’t look for a particular race or place — all they need is a human body, warm, moist and nutrient-rich. Unfortunately, even the scientific understanding of hosts, vectors and carriers has been appropriated to reinforce social prejudices.

Stigma produced in the churn of a pandemic has a long afterlife. No one understood that better than Mary Mallon. Quarantined for more than a quarter of her life, her name is still synonymous with disease.

The same aggressive hounding of the afflicted persists today. Desperate to maintain quarantine, governments are publishing patient names and addresses, affixing door stickers, stamping their skin with indelible ink, all of which violate medical ethics and could lead to social ostracism.

And we stand today facing the same question a poor, immigrant woman asked of society at the beginning of the 20th century. Is it necessary to forego humanity in order to save human life?

This article was originally published on The Hindu (3 April 2020): https://www.thehindu.com/society/pandemics-and-prejudice-when-there-is-an-epidemic-social-prejudices-resurface/article31246102.ece

Amitangshu Acharya is a Leverhulme Trust Ph.D Scholar at University of Edinburgh, U.K., and a Fellow at Konrad Lorenz Institute, Austria.

Comments by Ritti Soncco