For Art in Mind, my colleagues and I sought the help of nine co-curators – six students and three staff members from the University – to choose the objects that have formed the basis of our digital exhibition. I am so pleased that we decided to experiment with a co-curatorial model, because this is a format that I have always been very interested in.

Being a curator is an amazing and fascinating experience because you get to witness the physicality of the past and share this important knowledge with others, but it is also important to acknowledge that the position comes with a high degree of power and privilege, especially over those communities historically underrepresented in museums. While I am very passionate about using my position as a curator to spotlight marginalised histories, as a white person who comes from a university background there are some topics that I simply won’t be able to do justice to. In that instance, it would be crucial for me as a curator to seek the perspectives of communities who can provide a more meaningful interpretation of those historical narratives. Co-curated projects like Brothers in Arms by the National Army Museum in London highlight the importance of providing marginalised communities with the platform to tell their own histories. Funded by the Esmée Fairburn Collections Fund in 2015, Brothers in Arms was a project aimed at cataloguing and digitising the Indian army collection, an extensive but underutilised area of the archive. Project Officer Jasdeep Singh Rahal thought that it was crucial that British Asian communities were consulted in this project, and carried out a series of community reinterpretation workshops. There were some fascinating outcomes; for example, the National Army Museum has a sword in its collection which was initially catalogued as having a ‘meaningless inscription’ because so little was known about the object. However, members of the British Asian community were able to translate the inscription, which tied the sword to its owner and resulted in the realisation that this was in fact a valuable item in the collection. Stories like this demonstrate the value of consulting co-curators – without the help of members of the community, the National Army Museum may never have found out more about the provenance of this object. While being beneficial to the museum itself, such an achievement also has a positive impact on the community. It is fantastic that they had the chance to see rare objects relating to the life stories of those that they identify with, as well as help to breathe life back into objects from the past which may otherwise have been disregarded or forgotten about.

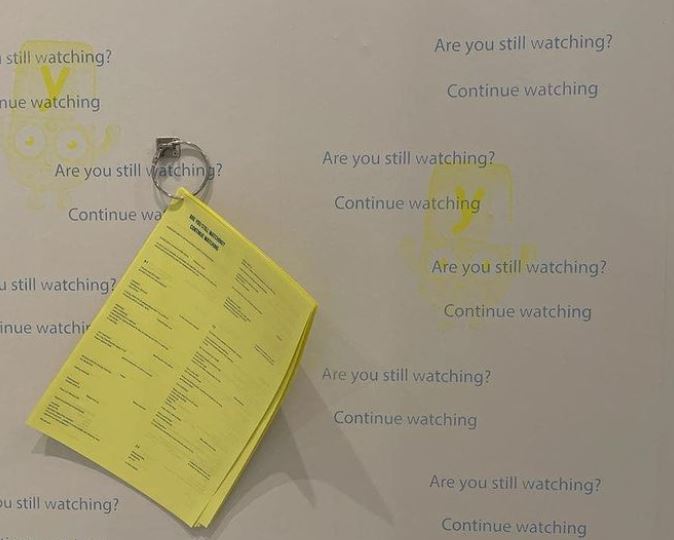

In the same vein, there are many people who are intimidated by museum and gallery spaces and view them as ‘stuffy’ and ‘boring’ because they cannot see their own lives reflected in the materials that are on display. A co-curatorial model allows audiences more freedom to choose what they want to see from heritage collections, which increases the likelihood of making it more widely relatable and appealing. One particularly novel example of a co-curated exhibit is My Kid Could’ve Done That! displayed by The Holburne Museum in Bath in late 2021. The title pokes fun at disparaging comments often made towards contemporary artworks, while also turning the statement on its head and taking a unique approach to artmaking. In this exhibition, 15 contemporary artists were invited to create artwork alongside their children to tell a wider narrative about the complex relationships between parenting and labour and the changing nature of childcare as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. I love this exhibition for obvious reasons – of course, having children involved in creating the artwork on display is very charming – but I also appreciate how it helps to humanise the artists involved in the exhibition and give visitors insight into their creative process. For example, in the exhibition sculptor and installation artist Harriet Bowman wanted to create a piece with her son Len that represented the reality of sharing a studio space with a young child four days a week. To do this, she worked with Len to make a sheet of wallpaper to cover the entire back wall of the gallery that features screen prints of the television shows that Len watches whilst Harriet has a tight deadline to make. It is also here that visitors can also read a booklet full of anecdotes that document the experiences Len and Harriet have shared during this time. Examples include instances of work being broken, tantrums, struggling to fit prams in lifts, constant tidying, and going to meetings with leaking breasts. While I’m not a parent myself, the fact that an accomplished artist like Harriet also struggles with managing work and childcare like many other parents feels very relatable and gives me more appreciation for the work that she is able to create. While this sparks an important conversation about how the labour involved in parenting can affect an artist’s work, the witty title along with involving children in the displays suggests this exhibition doesn’t take itself too seriously, which rightfully challenges the notion that engaging with art has to be a solemn, serious experience. I think this co-curated art exhibition is very radical – it is a straightforward idea that is easy for a wide range of audiences to understand and engage with, while also going against traditional power dynamics between the artist on display and the visitor viewing the work. ‘y’, a 5 X 3m rectangle of screen printed wall paper with a riso printed pamphlet. Created by Harriet Bowman and her son Len Bowman for, ‘My Kid Could’ve Done That!’, Holburne Museum, 2021. Screenshot taken by the author from @harrietbowman on Instagram. All rights reserved to the artist.

‘y’, a 5 X 3m rectangle of screen printed wall paper with a riso printed pamphlet. Created by Harriet Bowman and her son Len Bowman for, ‘My Kid Could’ve Done That!’, Holburne Museum, 2021. Screenshot taken by the author from @harrietbowman on Instagram. All rights reserved to the artist.

Brothers in Arms and My Kid Could’ve Done That! are such drastically different projects, and I think that this is a testament to the vast diversity of co-curation. The fact that there are endless ways to co-curate is very exciting, and this is one of the many reasons why I think co-curation is the future of heritage. I hope one day, all heritage projects have a co-curatorial element, whatever form that may take.

Bibliography

Tim Jonze, “‘It’s not cutesy’: the art show co-curated by a five year old” in The Guardian Newspaper, 31st August 2021. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/aug/31/its-not-cutesy-the-art-show-co-curated-by-a-five-year-old [Last accessed 16/05/2022].

“My Kid Could’ve Done That!”, Holburne Museum Official Website. Available at: https://www.holburne.org/my-kid-couldve-done-that/ [Last accessed 16/05/2022].

Jasdeep Singh Rahal, “Co-curating with communities: understanding and underused Indian army collection”, Museums Association Official Website, 8th September 2015. Available at: https://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/opinion/2015/09/09092015-co-curating-with-communities/# [Last accessed 16/05/2022].

“Co-curated exhibitions, partnerships and collaborations” Creative Museum Official Website. Available at: http://creative-museum.net/c/creative-practices/co-curated/ [Last accessed 16/05/2022].

Charlotte Connelly, “Co-curating The Year That Made Antarctica”, University of Cambridge Museums and Botanic Garden Official Website, 8th August 2017. Available at: https://www.museums.cam.ac.uk/blog/2017/08/08/co-curating-the-year-that-made-antarctica/ [Last accessed 16/05/2022].

“Co-curating and “Making Space for Divergent Perspectives”, Asia Society Official Website. Available at: https://asiasociety.org/museum/co-curating-and-making-space-divergent-perspectives [Last accessed 16/05/2022].

Leave a Reply