Our exhibition, Art and Mind, will be completely digital due to the unpredictable nature of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, while we have known that our exhibition would be digital from the outset of our project, this was not the case for many of the museums and galleries that had to swiftly adapt and make their physical exhibitions digital as a result of the first lockdown in 2020. According to King et al. (2021), of the 88 temporary on-site exhibitions in museums and galleries across Britain which were meant to take place during the months of March-June 2020, less than a quarter provided a digital adaptation; instead, the majority of exhibitions were extended, postponed or cancelled.

Such statistics have encouraged me to reflect on how the pandemic has influenced the digital output of museums and galleries over the last two years. As JiaJia Fei, the Consulting Director of Digital at the Jewish Museum in New York has argued, previously museums and galleries made exhibitions solely with an in-person audience in mind; only after the physical exhibition preparations were complete would heritage professionals consider how the information might be translated digitally. In light of coronavirus, however, the reverse is now commonplace; “Now that physical spaces are no longer the priority, the cultural sector is rushing to adapt events, exhibitions and experiences for an entirely digital-first audience” (my emphasis, The Guardian Newspaper, 2020).

This “digital-first audience” is much larger than the traditional in-person audiences museums are used to engaging with, but I feel that the ability to reach new audiences has been one of the largest strengths of digital heritage content created during the pandemic. I certainly witnessed this whilst working at the National Library of Scotland. While the Library has a physical events space, it has a small capacity of around 40 and is only accessible to those who can travel to central Edinburgh. Since they started hosting events via Zoom last year, they have had attendees from over 85 countries and can have as many as 500 people attending one event. As you may have seen, over the first lockdown people from around the world engaged with the J. Paul Getty Museum in recreating artworks from their collection using items around their home, highlighting the ability of heritage organisations to not only interact with global audiences in a meaningful way, but also provide those audiences with a means of escapism during a difficult time such as a pandemic.

:focal(542x285:543x286)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/15/1b/151b8482-a37f-4be7-91d4-5b1c3e7ce231/vermeer_astronomer_composite.jpg)

Johannes Vermeer’s The Astronomer, 1668, (left) and recreation by Zumhagen-Krause and her husband featuring tray table, blanket and globe (right) Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum.

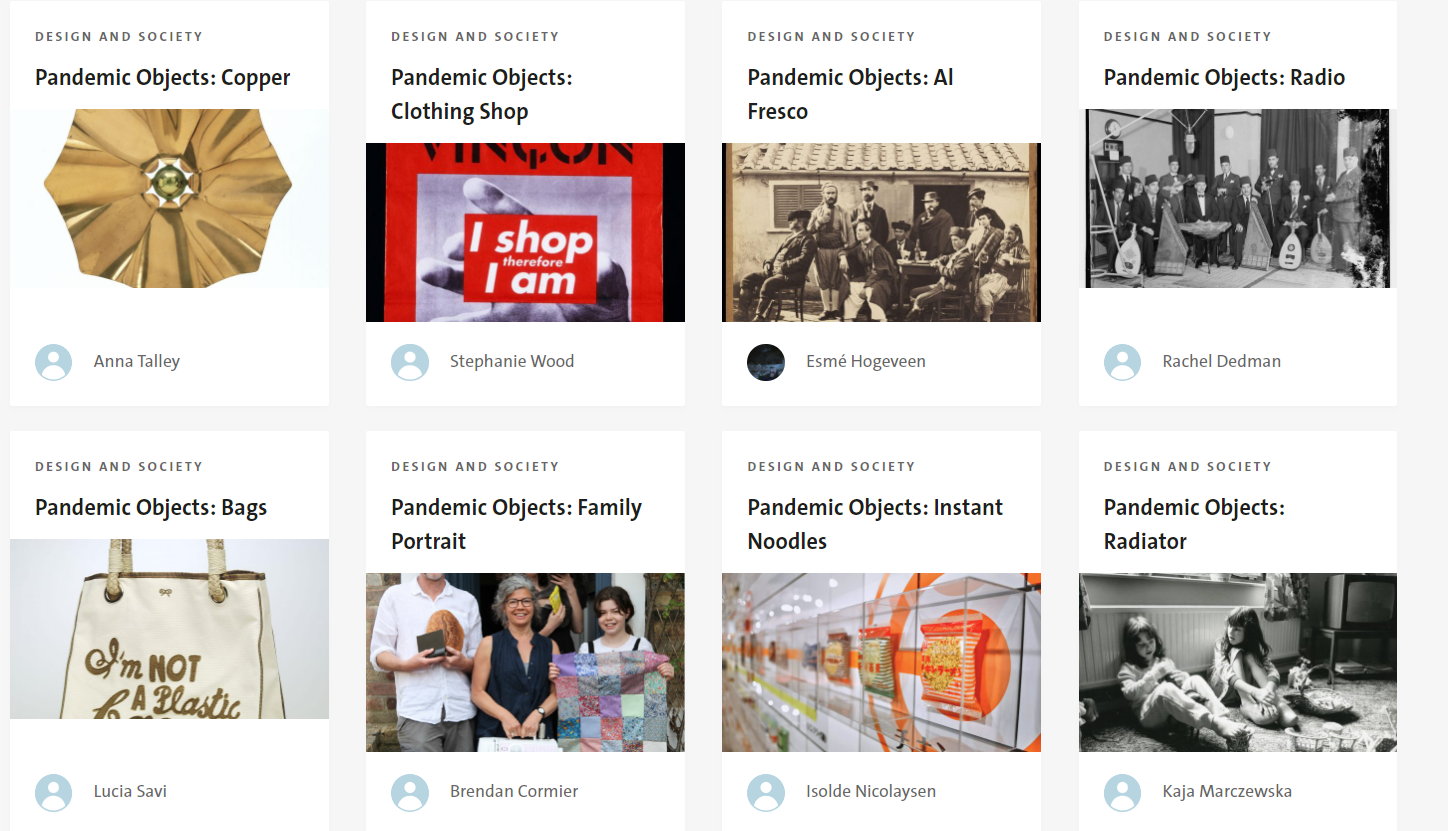

Another project that was borne out of the pandemic that stood out to me was the V&A’s Pandemic Objects, a series of essays that provide a history of everyday objects which have taken on a new meaning as a result of the coronavirus lockdown, such as flour (due to the shortages of the ingredient as a result of an influx of people baking their own bread) potted plants (many of us without access to a garden relied on houseplants to feel closer to nature when we couldn’t leave the house) and exam and exercise books (for many children, schooling became entirely online practically overnight). While text-heavy content like an essay series has the risk of not being appealing to a broad range of audiences, I think the link to objects that so many of us had begun to associate with our lockdown experiences was something exciting and new, and for me was a fantastic way to put the pandemic into perspective. When the first lockdown hit I struggled to recall what life was like before COVID-19, but strangely, learning about the wider histories of these essential lockdown items helped me to remember, as well as have more meaningful and personal engagement with some of the V&A’s collections.

A screenshot of the Pandemic Objects website, showing a selection of the everyday lockdown objects that have been written about. All rights reserved to the Victoria and Albert Museum.

However, although the pandemic has encouraged many GLAM organisations to improve and diversify their digital engagement, at the time of writing coronavirus restrictions have massively lifted, and many GLAM organisations are beginning to return to a level of ‘normal’ by offering in-person events and exhibitions again. While this is fantastic, I am also concerned that this means digital provisions will stop or taper significantly. As Prowse (2021) has noted, disabled people have been pleading with cultural institutions to offer alternatives to attending in-person events for years, and it was only when abled people were affected by the lack of digital events did it become a reality. The coronavirus pandemic has shown us that consistently offering a digital alternative is possible and beneficial, and as a sector I feel we have a responsibility to our audiences (especially to our disabled audiences) to maintain this provision as much as possible.

Nevertheless, it is still the case that digital heritage content has a lot of unrealised potential. As Hoffman (2020) has pointed out, many museums and galleries still try to replicate their physical premises in a digital space when creating online exhibitions. This can impact the accessibility of these digital heritage resources, as marginalised communities who feel underrepresented and intimidated by physical heritage spaces are then just being met with the same barriers, just online. As a sector, it is crucial that we do not assume that because something is digital, it automatically is engaging and accessible. We need to take advantage of the blank canvas that a digital environment has to offer, and how that has exciting possibilities for being more welcoming and accommodating to audiences who would otherwise not engage with us.

Bibliography

Laura Feinstein, “‘Beginning of a new era’: how culture went virtual in the face of crisis” in The Guardian Newspaper, 8th April 2020. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2020/apr/08/art-virtual-reality-coronavirus-vr [Last accessed 28/01/2022].

Jennifer Nalewicki, “This Museum is Asking People to Remake Famous Artworks With Household Items” in Smithsonian Magazine, 31st March 2020. Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/museum-asking-people-remake-famous-artworks-with-household-items-180974546/ [Last accessed 28/01/2022].

Ellie King et al. “Digital Responses of UK Museum Exhibitions to the COVID-19 Crisis, March–June 2020″ in Curator: The Museum Journal (64:3, 2021) pp. 487 – 504.

Sheila K. Hoffman, “Online Exhibitions during the COVID-19 Pandemic” in Museum Worlds (8:1, 2020) pp. 210-215.

Vassiliki Kamariotou et al. “Strategic planning for virtual exhibitions and visitors’ experience: A multidisciplinary approach for museums in the digital age” in Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, (Vol. 21, 2021) pp. 1-11.

Lukas Noehrer et al. “The impact of COVID-19 on digital data practices in museums and art galleries in the UK and the US” in Humanities and Social Sciences Communications (8:236, 2021) pp. 1-10.

“Online exhibitions: solutions for museums, galleries and other cultural organizations” Surface Impression website. Available at: https://surfaceimpression.digital/online-exhibitions/ [Last accessed 28/01/2022].

“HAUSER & WIRTH presents inaugural online exhibition, ‘louise bourgeois drawings 1947-2007′” DesignBoom website. Available at: https://www.designboom.com/art/hauser-wirth-inaugural-online-exhibition-louise-bourgeois-drawings-03-24-2020/ [Last accessed 28/01/2022].

“Pandemic Objects”, Victoria and Albert Museum official website. Available at: https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/pandemic-objects [Last accessed 12/05/2022].

Jamila Prowse, “The future of art spaces: How accessible is the virtual space?” in 1854 Photography, 17th June 2021. Available at: https://www.1854.photography/2021/06/the-future-of-art-spaces-how-accessible-is-the-virtual-space/ [Last accessed 12/05/2021].

Leave a Reply