For my degree in Social Psychology, back in 2017 I wrote a dissertation about intersectionality and Facebook Feminism in Brazil. I had two main reasons for that: the perception that intersectionality was a growing concern for feminists in Brazil and the fact that this specific platform had become so popular for fast feminist activism that “Facebook Feminism” had become an easy derogatory expression.

After reading a couple of qualitative research focused on one specific Facebook page or movement and limited by narrow time frames, I thought it would be good to get a broader view of the field, so I decided to do a wider-reaching data collection and exploratory analysis. More than just satisfying my own curiosity, I wanted to contribute to further research (although I am still to work on writing and publishing a paper about it). Today I want to share a fragment of what I found out.

Intersectionality

Simply put, the intersectional approach posits that thinking about oppression requires that we consider all the relevant multiple forms oppressions at play and how they relate for creating specific outcomes. So, for feminist analysis, that involves going beyond just gender, as not all women navigate the world in exactly the same conditions. Markers of oppression vary widely across cultures, but overall there is an agreement that the minimum 3 categories of difference that should be taken into consideration are gender, race and class. That being said, it is not a simple task to try to attribute the presence of those markers to Facebook posts or, really, any text.

What I did and what I found

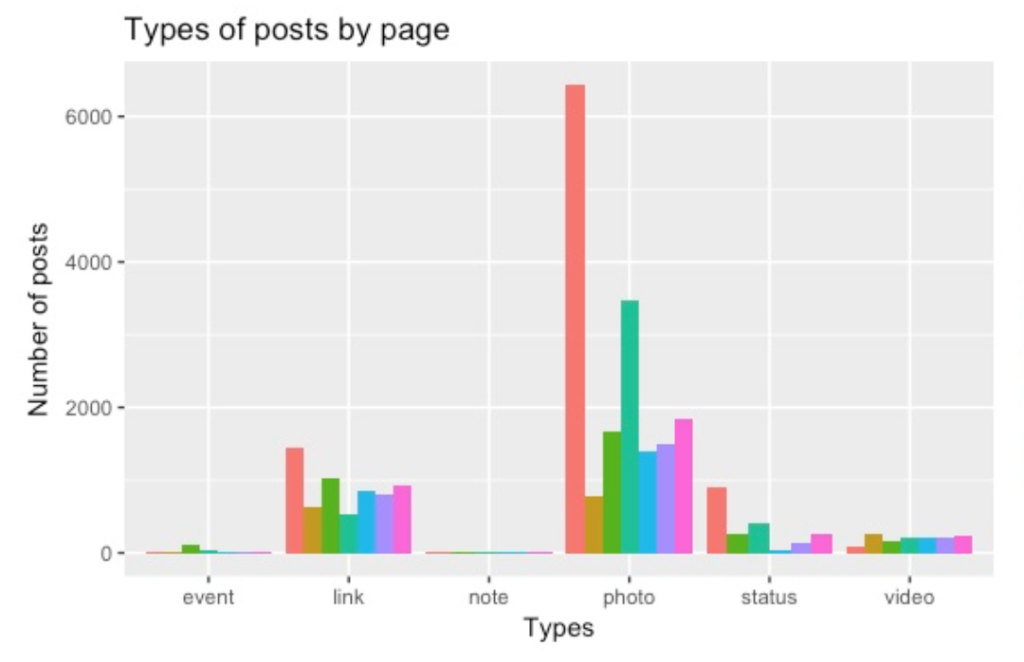

I collected posts from the six most liked Facebook pages in Brazilian Portuguese that I could identify using the platform’s research tool (which is in itself very limiting). I chose only the pages that did not explicitly identify whit any specific strand of Feminism. The most popular one at that time (July 2017) had 1.242.852 likes; the least, 727.575. The gathered corpus had a total of 26.890 posts published from mid-2013 up to that moment.

A bar chart representing the number of posts by type. Different colors represent the different pages analyzed.

The first thing I could immediately conclude was that any serious future analysis should focus on images, not text, as “photo” is the predominant type of post. That is reinforced by the fact that only 35% of the collected posts had text with more than 140 characters.

A word cloud of most common pairings for the word “Feminism”.

A word cloud for the most common pairings for the words “woman” and “women”.

In order to try to observe what kinds of Feminism were enunciated in the posts, I used n-grams to see which words most commonly accompanied “Feminism”. “Intersectional” showed up only 24 times, while “black Feminism” occurred 50 times.

That focus on racial identity was also predominant when repeating the same process using the words “woman/women” to observe which categories of women were most frequently enunciated in the posts. “Black women” had 579 mentions, while “white” had 266 and other WoC had 46.

Whether or not this really says anything about intersectionality in Facebook Feminism, it is great to see some emphasis on blackness in these spaces. White middle-class women are traditionally over-represented in Feminism; in a country where most of the population identifies as black, it only makes sense that any new approaches to mainstream feminist conversation elevate black women’s voices and concerns.

Intersectionality does not have to be enunciated to exist. My simple exploratory methods did not allow for more nuanced inquiries, but more complex approaches could provide a deeper understanding of this form of digital activism.